2006-12-01

Abstract

Jeffrey Aboud investigates the buzz surrounding trojan crimeware.

Copyright © 2006 Virus Bulletin

In recent months, the buzz around trojan crimeware has become more prevalent in industry readings. But is the threat real or imagined? Is it something against which we should be building defences, or is it just a marketing ploy, developed in an attempt to sell more security software?

Some of the lack of clarity around these issues may be due, in part, to the variety of labels used to identify this threat. Some security companies and industry organizations refer to these threats generically simply as 'crimeware' or 'cybercrime'; others categorize each type more narrowly, using more specific labels such as 'trojan spyware' or 'trojan malware'.

Regardless of the label used, we define this threat as a malware attack that employs spyware or backdoor trojans. The attack is financially motivated, developed and deployed with the specific intention of stealing sensitive personal information such as online passwords, credit card information, bank credentials, or social security numbers.

According to a recent report published by Symantec [1], five of the top 10 new malicious code families reported during the first six months of 2006 were trojans, and 30 of the top 50 malicious code samples released during that timeframe sought to expose confidential information. Similarly, the national Computer Emergency Response Team for Australia (AusCERT) reports a 46% increase in the total number of identity theft trojan incidents reported between January and October this year, compared with the same period in 2005 (Figure 1).

In addition to the rapid growth of trojan spyware and the rest of the crimeware family, the pervasive nature of this threat type, coupled with the relatively high potential for its victims to incur losses, easily justifies the elevation of its status in the threat world.

Perhaps the single largest change in the security industry in recent years has been the evolution of the intent of malware authors. Whereas 'traditional' viruses were written for the predominant purpose of gaining notoriety, today's bent is definitively in the camp of financial gain.

According to David Perry, global director of education at Trend Micro, the number of destructive viruses has historically been small, with the vast majority of viruses doing nothing but replicate. 'We saw the highest number of destructive viruses around 1999–2000, but they've declined steadily since,' explains Perry. 'Nowadays, almost everything we see has a motive.' Mimi Hoang, group product manager for Symantec Security Response, agrees. 'The old metric of success for a malware writer used to be who could be first to exploit a particular vulnerability or develop some cool new virus,' says Hoang. 'But today, the metric is based on who can achieve the most comprehensive list of coverage. We see a combination of techniques – such as a series of targeted attacks, coupled with the use of small bot networks – to help spread the infection as far as possible, while staying small enough to remain under the radar.'

This metamorphosis has fuelled an abundance of developments that have become essential components of today's threat landscape. Rather than 'script kiddies', today's malware writers are often skilled programmers, well-versed in a variety of advanced programming techniques; they have the financial wherewithal to obtain formal training and robust software development tools, all of which was out of reach in the recent past. Rather than seeking fame and glory, today's malware authors prefer to go unnoticed, favouring a series of relatively small, targeted infections, rather than a single large-scale attack that attracts a flurry of attention; and instead of individuals who worked on their own with no apparent purpose for their actions, today’s threats are increasingly developed by – or with the backing of – organized crime rings, with financial gain as the sole intention behind their actions.

The means by which these threats can achieve their goal is seemingly limitless. Depending on how it is deployed, a trojan spyware threat can be used to steal anything from passwords, credit card information and the like from consumers, to corporate login credentials from unsuspecting enterprise users, thereby giving the malware owner the keys to the company's most sensitive information.

According to a report published by the Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG) [2], the ways in which trojan crimeware can be employed to achieve financial gain include:

Theft of personal information.

Theft of trade secrets and/or intellectual property from businesses.

Distributed denial-of-service (DDOS) attacks.

Propagation of spam.

'Click fraud' (the simulation of traffic to online advertisements).

'Ransomware' (encrypting a user's data, then extorting money from them to have it restored).

Use of consolidated personal information for furtherance of additional attacks.

Robert Lowe, computer security analyst at AusCERT, adds that most trojan crimeware serves multiple purposes: 'While these trojans have the primary purpose of stealing a range of personal information, including passwords from the compromised computers, these computers are able to be controlled [by the attacker] and used for other purposes to generate financial return, such as supporting further attacks, distributing spam and malware, hosting wares, or taking part in distributed denial of service attacks.'

A significant aspect of the trojan crimeware threat is the variety of distribution techniques that can be utilized to avoid detection. The trojan can be distributed by attaching the code to email and using tried-and-true social engineering techniques to entice users to launch the executable; it can piggyback onto a legitimate application, to be launched simultaneously with the host application; or it can lurk on either a legitimate or sinister website. This list is by no means exhaustive, providing just a flavour for the variety of distribution methods that are at the disposal of this new breed of malware author.

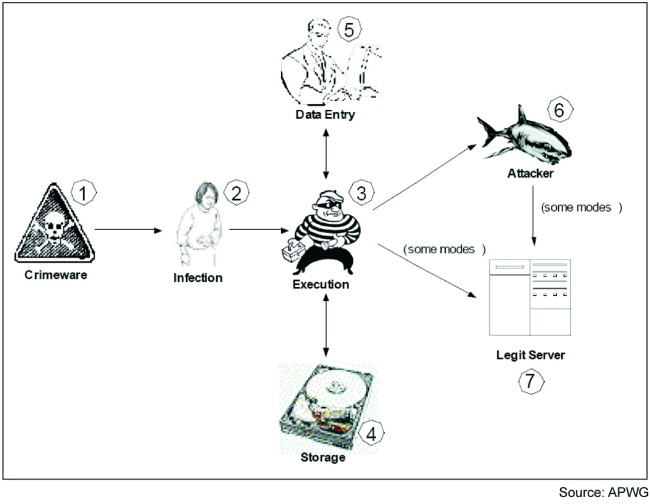

Figure 2 illustrates the transmission methods and corresponding infection points currently used by various types of crimeware. One obvious transmission method that is curiously absent from the list is spam – as are all other forms of mass transmission. Though trojan crimeware can certainly be distributed by mass-mailing techniques, the trend nowadays seems to be that of maintaining a low profile. As such, most crimeware authors tend to favour a series of small, highly targeted attacks over those released to the masses.

| Attack type | Infection point | Data compromise point |

| Keylogger/screenlogger | 2 | 5 (I/O device) |

| Email/IM redirector | 2 | 6 (network) |

| Session hijacker | 2 | 6 (network) |

| Web trojan | 2 | 5 (I/O device) |

| Transaction generator | 2 | N/A |

| System reconfigurator | ||

| Hostname lookup | 3 (execution) | 5 (web form) |

| Proxy | 3 (execution) | 6 (network) |

| Data theft | 3 (execution - ephemeral) | 4 (storage) |

Figure 2. Anatomy of a crimeware attack.

The targeted approach offers the cyber criminal two key benefits. First, by targeting a specific group with similar backgrounds or interests, social engineering techniques can be tailored to appeal specifically toward the commonality of the targeted group, resulting in a higher-than-average chance of success. Second, by keeping the attack small and precise, there is less chance that it will be noticed either by the user or by automated security software.

Once executed and installed, the trojan can remain on the system conceivably forever, waiting for the action that is set to awaken it. And since the longer it remains on the system the higher its likelihood for success, not arousing suspicion is most certainly to the author's advantage.

Perhaps more important than the distribution method, however, is the complexity with which many of these threats are written, in an attempt to propagate widely, while still avoiding detection. As mentioned, crimeware authors stand to gain potentially extraordinary financial rewards if they accomplish their goals. As such, it is well within their interest to make investments in their activities through the purchase of professional tools, training, and the like. And many already enjoy the financial backing of criminal organizations, making it easier to make such investments.

Due to these enhanced capabilities, many of the finished products are quite robust, making their detection and removal non-trivial, at best. For example, many crimeware samples have an overwhelming replication capability: once one process is stopped, the code automatically starts another. Some have the capability to start a large number of simultaneous processes. According to Hoang, during the first six months of 2006, Symantec noted trojan code initiating additional processes at an average rate of 11.9 times per day – up from an average of 10.6 times per day in 2005.

Moreover, some observed samples have blended this replication aptitude with polymorphic capabilities, meaning that each time the malware replicates, the ensuing code will be different from the other copies. Since the code will be a slightly different file each time it installs, it is more difficult to detect and remove.

Similarly, the resurgence of rootkit technology over the past 18 months adds yet another layer of complexity to the problem. Over the course of the past year, some crimeware samples discovered in the wild have utilized rootkit technology to mask their processes. Between their cloaking capabilities and their level of system access, rootkits can offer trojan crimeware unparalleled power, as well as the ability to work silently in the background of a system. This new found power can grant crimeware access to more sensitive information, and over a longer period of time – therefore dramatically increasing the likelihood that the user will incur financial losses as a result of the infection.

Though not intended to be an exhaustive list, the following are some guidelines to help protect a company's assets from crimeware:

Keep security definitions updated. Set pattern updates to daily. This is the first line of defence against viruses that can also be hosted on web pages. Many vendors even provide beta definitions with the same quality as the daily download. These should be applied when the threat is severe. Likewise, keep systems patched – particularly systems that are accessible through the corporate firewall.

Make sure the security protection is complete – and overlapping. Regardless of the security provider you use, they should offer a comprehensive, integrated suite, which includes multiple layers of protection – from the gateway, to server level, to individual clients. This protection system should be designed by utilizing overlapping and mutually supportive defensive systems. If laptops and other removable devices that can be taken out of the office environment are part of the network configuration, it is essential that the security solution also includes a built-in client-side firewall and an anti-spyware engine, to prevent spyware, backdoors and bots from entering the network when the removable devices are reintroduced. In the age of VoIP, VPN, mobile and cellular devices with network and WiFi capability, border security has been reduced to a myth.

URL filtering. Make sure the anti-virus or anti-spyware product employed has a URL-filtering feature to prevent accidental clicks on known malicious sites. A substantial reduction in this risk can be attained by utilizing IP reputation services, which reside at the gateway.

Educate the users. One of the most basic – yet critical – aspects to protecting a company's resources against a host of threats is to educate users on the need to conduct day-to-day online activity in user-privilege mode, rather than in administrator-privilege mode. This simple difference limits substantially the malicious user's access privileges to system resources in the event of an attack. Additionally, be sure that users are familiar with security best practices, as well as company security policies. It is also prudent to ensure that they understand some of the warnings their security product will provide them, and what these warnings mean (including what actions, if any, they should take when they are presented with such a warning).

Take central control. First, disable any services – inbound or outbound – that are not needed, to limit exposure to only those ports that are necessary to the operation of the business. Second, employ group policies to limit access to critical services, thereby limiting the potential for damage. Third, segregate access points physically and logically and install Network Access Control (NAC) services to ensure all users follow a base model of security. And fourth, configure mail servers to block proactively or remove email attachments with extensions such as .VBS, .BAT, .EXE, .PIF, and .SCR, which are commonly used to spread security threats.

So, is trojan crimeware worth all the fuss? Though the threat is not large enough to make the evening news, it is out there and can cause some real financial losses. Better to build some defences to combat this threat, than to be sorry later.