2012-02-01

Abstract

Even in a mobile world, the principles of malware analysis remain the same. John Foremost takes us through the basic steps in the static analysis of mobile malware.

Copyright © 2012 Virus Bulletin

Even in a mobile world, the principles of malware analysis remain the same. Files can be captured through many different mediums, such as downloads from an application market or website, through a mobile device, through emulated lab environments, downloads from mobile malware repositories and more. Once captured, the study of the file begins with the age-old static analysis, with tools and tactics customized for mobile malware. The examples provided in this article are focused on Android threats, but the principles apply to all mobile malware analysis.

All files, malicious or not, have basic metadata details that are pertinent to an investigation. The basics that should be collected include (but are not limited to) hashes like MD5 and SHA1, file size, and other properties that may exist for the file. These may include: filename extension, header, file type (Linux command), packer details (scanning and manual inspection methods), etc. Once collected, all file information needs to be organized into a research archive, as other similar samples or details may be discovered through the analysis process.

Internet searches should then be performed against all the data collected to look for related reports, abuse, or other information of relevance to the investigation. This may result in the discovery of anti-virus reports, related samples, dates and times of incidents and other data of interest. If the researcher is just trying to find out basic information – such as attempting to confirm the maliciousness of a file, a simple MD5 query can quickly provide the answer.

For example, e7584031896cb9485d487c355ba5e545 is the MD5 hash value of a known malicious mobile malware sample. A Google search on this value brings up three links which both name the sample and help to identify some functionality.

Several web-based freeware scanners exist for processing mobile malware:

Avast: http://onlinescan.avast.com/

Jotti’s Scanner: http://virusscan.jotti.org/en

Metascan: http://www.metascan-online.com/

NetQin: http://scan.netqin.com/en/

VirusTotal: http://www.virustotal.com/

The results returned by such scanners are not conclusive, but they do often help identify family and/or possible functionality. Also, metadata may exist on some sites such as VirusTotal, where users supply links, comments, or related data when uploading or analysing a sample of interest.

Application-based scanners may also be used to scan mobile malware. For example, a wealth of anti-virus applications exist for Android, ranging from Zoner AntiVirus Free to AVG Mobilation Free and Kaspersky Mobile Security. The downside of using such solutions for analysis is that the applications must be installed, configured and maintained on a lab device or in an emulated environment – a notable task that may be beyond the scope of the average department attempting to triage new samples.

DexID is a great freeware tool for identifying known Android malware. It can be obtained via hxxp://dl.dropbox.com/u/34034939/dexid.zip. (Dexid.dat is also required to obtain updated signature data associated with the tool.) The tool installs easily on a Linux system, requiring several Perl modules in order to run the tool as configured. The following is an example of part of the verbose output for a file analysed by DexID:

com.droiddream.bowlingtime.apk->classes.dex (D4FA864EEDCF47FB7119E6B5317A4AC8->ADD472D8D4A39C602AD31E23ACE4F3BE)

Header:

Magic: “dex”

Version: 035

Checksum: 8F24DD46

SHA-1: 00BC064674921016F23FCC0C92FAE51D8216C9A5

FileSize: 303300

HeaderSize: 00000070

Endianness: 12345678

LinkSize: 0

LinkOffset: 00000000

MapOffset: 00049FF4

[snip…]

5B 20 038B | iput-object v0, v2, field@038B ; com.phonegap.AccelListener com.phonegap.DroidGap.accel

22 00 016C | new-instance v0, type@016C ; com.phonegap.CameraLauncher

70 30 06B1 0230 | invoke-direct {v0, v3, v2}, method@06B1 ; void com.phonegap.CameraLauncher.<init> (android.webkit.WebView, com.phonegap.DroidGap)

5B 20 0394 | iput-object v0, v2, field@0394 ; com.phonegap.CameraLauncher com.phonegap.DroidGap.launcher

22 00 016F | new-instance v0, type@016F ; com.phonegap.ContactManager

70 30 06BB 0320 | invoke-direct {v0, v2, v3}, method@06BB ; void com.phonegap.ContactManager.<init> (android.app.Activity, android.webkit.WebView)

5B 20 0396 | iput-object v0, v2, field@0396 ; com.phonegap.ContactManager com.phonegap.DroidGap.mContacts

22 00 017A | new-instance v0, type@017A ; com.phonegap.FileUtils

70 20 0702 0030 | invoke-direct {v0, v3}, method@0702 ; void com.phonegap.FileUtils.<init> (android.webkit.WebView)

[snip…]Fuzzy analysis using ssdeep can help to identify samples that may be similar to one another. This can be very useful when trying to determine whether samples are closely related. For example, one variant may be discovered and another file may be suspected on the same network – perhaps a private update made to a device following infection. A fuzzy analysis helps to identify and/or locate related samples. Simply run a command such as:

ssdeep –rd DIRECTORY > results.txt

This command searches recursively through the specified directory to compare samples, writing the results into results.txt. A ‘-x’ option can also be used to compare hashes in two or more files. The output is similar to the example shown below, revealing the degree of correlation as a percentage:

Computer1.data.txt:C:\tank.apk matches

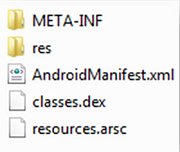

Computer2.data.txt:C:\guns.apk (68)Programs such as 7Z or WinZip can be used to extract files including Android APK files. Extracted APK files may contain DEX script, XML and ARSC. Analysis begins with the manifest file, such as AndroidManifest.xml. This file contains a long list of strings that may reveal potential functionality for the code, such as SMS messaging, networking, phone interactions and more. A good place to look up the functionality of Android-based strings is http://developer.android.com/reference/android/Manifest.permission.html.

The example shown below contains extracts from the Alsalah malware’s AndroidManifest.xml file. To avoid null character interpretations the file was opened in Notepad and then copied for primary ASCII strings of interest to review possible functionality leads. A few immediate leads are highlighted in bold text, and many more can be found by scanning through the output.

v e r s i o n C o d e v e r s i o n N a m e n a m e l a b e l i c o n c o n f i g C h a n g e s t h e m e a n d r o i d * h t t p : / / s c h e m a s . a n d r o i d . c o m / a p k / r e s / a n d r o i d p a c k a g e m a n i f e s t 2 . 4 c o m . s i l e r i a . a l s a l a h u s e s - p e r m i s s i o n a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . I N T E R N E T ‘ a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . A C C E S S _ F I N E _ L O C A T I O N ‘ a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . A C C E S S _ N E T W O R K _ S T A T E ) a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . W R I T E _ E X T E R N A L _ S T O R A G E a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . R E A D _ C O N T A C T S . a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . C H A N G E _ W I F I _ M U L T I C A S T _ S T A T E & a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . C L E A R _ A P P _ U S E R _ D A T A $ a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . B I N D _ I N P U T _ M E T H O D ! a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . W R I T E _ C O N T A C T S “ a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . C L E A R _ A P P _ C A C H E ( a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . A U T H E N T I C A T E _ A C C O U N T S # a n d r o i d . p e r m i s s i o n . (snip) A l S a l a h a c t i v i t y . a n d r o i d . A l S a l a h i n t e n t - f i l t e r a c t i o n a n d r o i d . i n t e n t . a c t i o n . M A I N c a t e g o r y a n d r o i d . i n t e n t . c a t e g o r y . L A U N C H E R s e r v i c e c o m . a w a k e . a l A r a b i y y a h a l A r a b i y y a h r e c e i v e r c o m . a w a k e . a r R a b i $ a n d r o i d . i n t e n t . a c t i o n . B O O T _ C O M P L E T E D A l S a l a h - P l a c e s . a n d r o i d . P l a c e s A l S a l a h - G P S . a n d r o i d . G P S A l S a l a h - H e l p . a n d r o i d . H e l p A l S a l a h - A b o u t . a n d r o i d . A b o u t A l S a l a h - S e t t i n g s . a n d r o i d . S e t t i n g s A l S a l a h - I m p o r t . a n d r o i d . I m p o r t A l S a l a h - S h a r e . a n d r o i d . E x p o r t A l S a l a h - H i s t o r y . a n d r o i d . H i s t o r y

DEX files (hxxp://code.google.com/p/dex2jar/) can be converted to JAR files in order to view them using programs like JD-GUI (hxxp://java.decompiler.free.fr/?q=jdgui), Djdec39, Cavajdemo or others. To convert files use the following options for Windows and Linux:

Windows: dex2jar.bat file.apk

Linux: sh dex2jar.sh file.apk

For example, Alsalah.apk unpacks to the following:

Once a DEX file has been converted into a JAR file, analysis can begin along the lines of a normal Java analysis, using the common aforementioned tools. A simple review of scripts often reveals functionality, URLs, or similar data of interest. The data can then be fed back into this process recursively so that all static data can be researched and analysed accordingly, until all avenues of static analysis have been exhausted.

The following is an example of a DEX file converted to JAR and then viewed within JD-GUI to identify URLs associated with the mobile malware:

While not ‘static’, sandbox options often follow static analysis and do not require any specialized lab set-up to triage mobile malware. Sandbox analysis for mobile malware is still emergent and may not be as timely as desired, but it is available free of charge (but note that the following site is sometimes down for maintenance): hxxp://www.mobile-sandbox.com/upload.php.

As illustrated in this article, static analysis alone can provide an excellent view into related abuse, related malware samples and code functionality. Many individuals globally are beginning to develop new skills for mobile malware analysis. Our community needs to further develop and automate static solutions so that static analysis becomes a well understood and standard component in the analysis of mobile malware. Over time, dynamic solutions will become more prevalent and more robust, adding further support to the quest to understand malicious mobile applications and artefacts.