2012-06-01

Abstract

Recent years have been marked by an explosive growth of social networks, with Facebook becoming one of the most attractive channels for cybercriminal activity. Alin Damian analyses some of the malicious domains extracted from Facebook applications and posts.

Copyright © 2012 Virus Bulletin

Recent years have been marked by an explosive growth of social networks including Facebook, Twitter and Google+. At the start of 2011, Facebook had around 600 million registered members – that number is now fast approaching one billion.

This paper will analyse malicious domains extracted from Facebook applications and posts, based on scams detected by Bitdefender’s Safego product. Previous studies of malware on Facebook have tended to focus on revealing the ‘social engineering’ part of the attacks, analysing their content and the way they spread. We will try to go deeper, looking at the domains on which these malicious applications are hosted, and the connection between applications’ hosting domains and those associated with more traditional methods of threat distribution (spam, phishing, etc.).

With nearly a billion registered users, more than 2.7 billion ‘likes’ and comments per day, and a huge presence all over the world, Facebook has become one of the most attractive channels for cybercriminal activity.

This study is based on URLs extracted from over 20,000 scam items (posts, comments, videos, etc.) detected by our Safego product. From these items we have extracted around 10,000 unique URLs, approximately 50% of which point to Facebook pages and applications (Figure 1).

Our first goal was to determine how many of the domains were also encountered in more traditional methods of threat distribution. We found that almost 47% of the analysed URLs had previously been seen in other channels of threat propagation. We split these into four categories: malware, spam, fraud (scams) and phishing (Figure 2).

Next, we analysed the URLs that hadn’t been found on any blacklists. The most striking observation in this case was the large presence of URL-shortening domains and hosting domains.

Of the shortening domains, the most dominant service was ‘bit.ly’ (90%), followed by ‘t.co’, Twitter’s shortening service. It is interesting to note that the same malicious URLs are used across several different social networks, combining Facebook, Twitter and others.

When it comes to hosting domains, the situation is a little more balanced. ‘Blogspot.com’ is the domain that appears most often, followed by Amazon’s ‘amazonaws.com’, and ‘co.cc’, a well-known domain in the world of scams and fraud.

A few questions probably come to mind, such as ‘What are these companies doing to stop scams being hosted on their domains?’ and ‘How long are these websites available before they are taken down?’. Unfortunately, the answer to the first question is ‘Not very much’. Of 121 malicious domains hosted at ‘blogspot.com’, about 94% remained active after more than 20 days. We consider this to be too long. (According to [1], on average, a phishing domain lasts about three days.)

A recent dangerous Facebook application that comes to mind is a scam disguised as an invitation to view a leaked sex video.

When the user attempts to view the video they are prompted to install a YouTube extension (which, of course, is malicious code rather than a real YouTube extension). Once installed, the extension changes all newly opened browser tabs to a page advertising an adult chat service.

The scammer is also now able to impersonate the user (by reading the cookie stored on Facebook.com), advertise the scam and ‘like’ the scam’s Facebook page from the victim’s account.

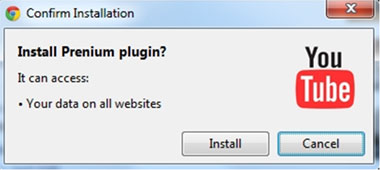

Another scam that deserves a mention is a ‘survey scam’ that tricks Firefox and Chrome users into installing a ‘Prenium’ plug-in.

An initial Facebook post invites the user to view a YouTube video showing an Italian model/TV host in an embarrassing situation. However, the user is told that they need to install a plug-in in order to view the video.

After following the instructions for installing the plug-in, the video described in the initial post is played – thus suggesting that this was a legitimate download. However, on returning to Facebook, just a loading icon is displayed.

Eventually, the browser redirects the user to a page stating ‘Your account was recently accessed from a location we’re not familiar with’. The text goes on trying to scare the user into believing that something is wrong with their Facebook account. However, the option to ‘Continue’ with the account verification process is not available because it is blocked by a scam survey.

In most cases, closing the page will get you out of this tight spot, but in this case the warning page comes back up no matter where you click: Profile, Messages, Privacy Settings etc. – all roads lead to the survey.

The browser add-on method as described above is a recent development in the world of social scams, and it seems to be quite efficient.

Ultimately, cybercriminals are seeking financial gain when creating and spreading malicious Facebook applications.

One of the main purposes of these Facebook applications is to spread malware, which can then be used in many harmful ways.

Some of the applications are intended to steal personal and sensitive information from users. For example, a user divulging his mother’s maiden name (the old standard used by many financial and banking sites to confirm identity and gain access to account information) can then be exposed to different types of attacks.

Other applications will lead to phishing websites, through which the cybercriminals may steal money or personal data.

The benefits for cybercriminals of the well-known ‘likejack’ campaigns are interesting. In a successful campaign, a Facebook page gains a large number of ‘likes’. This can be monetized in two ways:

The cybercriminal may change the content of the page and advertise an attractive contest with a large sum of money or other valuable item as the prize. A page with 100,000 likes will seem more credible to users than a brand new one. Users will then be duped into entering the competition via some method that generates revenue for the attackers. For example, a Facebook page that impersonated Orange Romania claimed to be organizing a contest in which an iPhone 4S was up for grabs. The page claimed that, in order to be entered into the prize draw, users had to send an SMS (at the cost of two euros).

A page with a large number of visits or ‘likes’ can be used to obtain money from advertising or pay-per-click websites.

To determine the lifespan of a Facebook application, we collected data for more than 1,000 applications over a 10-day period. On the 11th day, we rechecked the status of each of them. The results are plotted in Figure 6. We found, for example, that 33% of the applications collected on the third day remained active for eight days, until the end of our testing period.

We have seen that almost half of malicious URLs that spread in social media environments are also found in other traditional threats and the most dominant category found is ‘malware’. The other half is represented by URLs that are designed to be used in social media because they sit very well in this environment. We also showed that cybercriminals use malicious URLs in more than one social network, maximizing the chances of making a profit with minimum effort.

The goal of malicious Facebook applications is to help cybercriminals gain money from illegal activities – which may range from installing infected executables on users’ machines, to innovative and complex scams that trick users, or stealing sensitive information via websites that propagate through spam and/or which impersonate legitimate companies (phishing).