Cisco Umbrella (OpenDNS), USA

Copyright © 2017 Virus Bulletin

We propose a novel method unifying the interactions between client machines, hostnames and hosting IPs by building a tripartite graph consisting of tens of millions of vertices and edges. We then represent a sequence of tripartite graphs as signals to be mined in order to detect botnet attacks and online threats in general. With these signals, we ignore the lexical and move beyond traditional degree and centrality graph metrics. By pairing client machines to hostnames we reveal that the trademark of a bot in a botnet is three things: 1) the variety of hostnames it queries, 2) the popularity of the hostnames, and 3) the frequency with which the bot repeats itself. We explore three types of subgraphs to illustrate this fact: 1) clients pivoting to domains, 2) domains pivoting to domains, 3) hosting IPs pivoting to domains. In these subgraphs we cluster the vertices based on similar multi-dimensional signals reminiscent of traditional cohort analysis involving analysis of variance techniques. Using Hadoop technologies, we show that a large sequence of graphs translated into signals is scalable (to the millions) and can distinguish Necurs, Conficker, Suppobox, PykSpa, and more. In closing, we predict the number of domains within a family of AGDs by introducing a measure involving the chattiness and repetition of client machines.

A passive DNS graph (PDNS) consists of hostnames (sometimes called domains), registrants, hosting IPs, and ASNs. It has been proven that mining such a graph for subgraphs can isolate botnets [1]. However, there is currently no unified approach to incorporate time-dependent graphs that emerge when machines querying domains are modelled in the graph. In fact, the challenge of representing machines querying a domain at one time, but not another, similarly arises when a domain resolves to one hosting IP at one time, but not another. In short, the bot-like behaviour of clients is reminiscent of fast-flux behaviour in hosting IPs.

The classical problem of identifying botnet domains in a PDNS graph typically leverage either 1) lexical characteristics of domain names (n-gram entropy, perplexity) [2], or 2) traffic and static graph properties (measuring bursts in query volumes and similarity of inter-client traffic, respectively) [3, 4]. These insights build on the characteristic of algorithmically generated domains (AGDs) but miss the temporal nature of machines surfing the Internet, i.e. graphs change from one time window to the next (e.g. vertices and edges (dis)appear).

In this paper we propose a novel method to overcome these challenges and unify the interactions between client machines, hostnames and hosting IPs by building a tripartite graph consisting of tens of millions of vertices and edges. We then represent a sequence of tripartite graphs as signals to be mined in order to detect botnet attacks and online threats in general.

To that end, we define a set of graph properties that can be derived from one or more graphs. Noticeably, these properties ignore the lexical properties of a domain and move beyond traditional degree and centrality graph metrics. Further, we explore how the tripartite graph lends itself naturally to three forms of induced subgraphs: a) clustering a set of vertices based on a cluster of signals (then gathering neighbour vertices), b) starting with hand-picked seed vertices (then gathering neighbouring vertices attainable in a path of length 2), and c) starting with hand-picked seed vertices (then gathering vertices attainable in a path of length 3. These methods are explored by performing client pivoting to domain, domain pivoting to domain, and hosting IP pivoting to domain, respectively. In these subgraphs we cluster the vertices based on similar multi-dimensional signals reminiscent of traditional cohort analysis involving analysis of variance techniques.

By pairing client machines to hostnames and expanding these interactions in signals, we reveal that the trademark of a bot in a botnet is three signals: 1) the variety of hostnames it queries, 2) the popularity of the hostnames, and 3) the frequency with which the bot repeats itself. In other words, botnet domains are similarly defined by the three signals: 1) how many client machines query the domain, 2) how many other domains the client machines query, and 3) the frequency with which the client machines repeat. From these signals, we show how to predict the number of domains within a family of AGDs by introducing a measure involving the chattiness and repetition of client machines to approximate the number of domains an ideal classifier should catch.

In summary, using Hadoop technologies, we show that a large sequence of graphs translated into signals is scalable (to the millions) and can distinguish Necurs, Conficker, Suppobox, Pushdo, and more.

In Section 2, we review related work in botnet detection methods using lexical or traffic analysis. In Section 3 we introduce tripartite graphs. In Section 4 we discuss the vertex properties of one or more graphs, while Section 5 outlines querying machine vertex properties related to hostnames. In Section 6 we build signals from graph properties and in Section 7 we break the problem down into subtasks which can be scaled using Hadoop technologies. Sections 8, 9 and 10 explore subgraph signals from client pivoting to domain, domain pivoting to domain, and hosting IP pivoting to domain, respectively. Finally, in Section 11, we introduce a measure to infer the number of domains within a family of a campaign.

To our knowledge there is no prior work studying botnets found in signals derived from a sequence of bipartite graphs containing the client machine and hostname relationships. However, this work is influenced by the emerging field of graph signal processing [5].

Botnets are well studied where previous work frequently focused on parts of the tripartite graph discussed above and mainly dealt with the flux in lexical properties of domain names, or flux in hosting IPs.

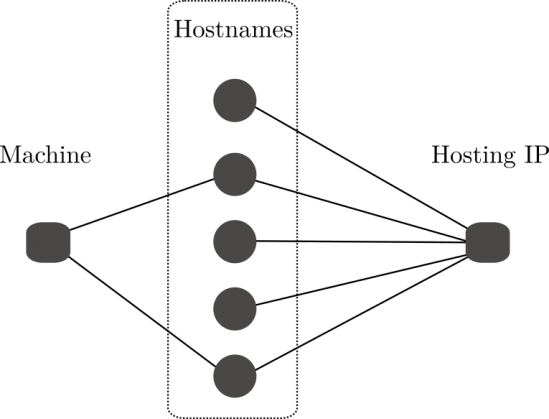

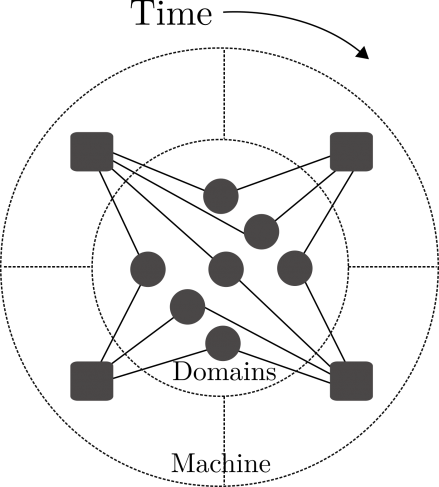

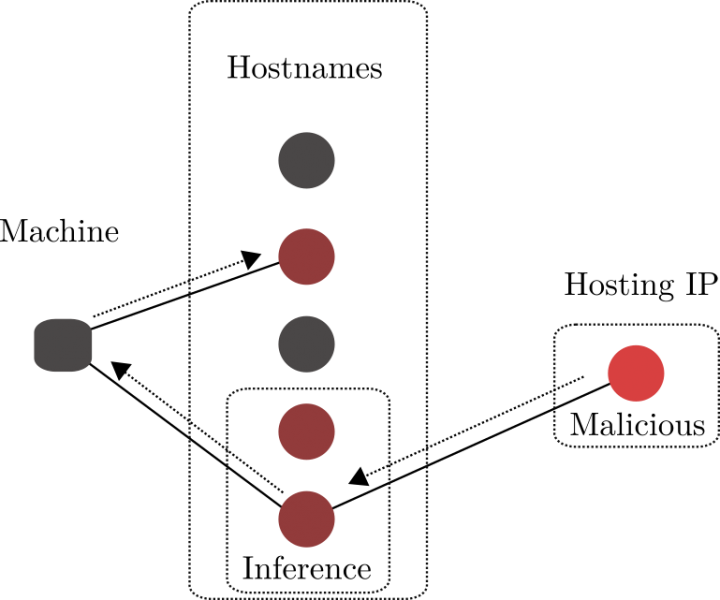

A k-partite graph is a graph whose vertices can be partitioned into k different independent sets where, intuitively, the edges link the sets. Naturally, the interactions of client machines querying hostnames form a 2-partite graph, also called a bipartite graph, with the two independent sets being machines and hostnames, respectively. Similarly, the hostnames (or domains) on a hosting IP form another 2-partite graph, with the two independent sets being hostnames and hosting IPs, respectively. Figure 1 combines these three independent sets to form a 3-partite graph. In this paper we explore various time-dependent bipartite graphs by taking hourly bipartite snapshots of client machines, hostname, and hosting IP interactions. These interactions are captured in different graph properties.

Figure 1: Example tripartite graph with independent sets: client machines, hostnames and hosting IPs.

Figure 1: Example tripartite graph with independent sets: client machines, hostnames and hosting IPs.

Given a graph G = (V, E), let υ ∈ V, we are interested in the neighbours, i.e. the number of vertices reachable by a path of length one from υ:

![]() We can then compute the degree of υ as | N(υ) |.

We can then compute the degree of υ as | N(υ) |.

Further, we can compute the neighbour degrees of υ:

![]() Given that the elements of ND(υ) are counts and therefore natural numbers, we can compute summary statistics such as the mean, median, and other percentiles of ND(υ).

Given that the elements of ND(υ) are counts and therefore natural numbers, we can compute summary statistics such as the mean, median, and other percentiles of ND(υ).

Further, given two graphs G and H with the same vertex υG and υH representing vertex υ embedded in G and H, respectively, we can compute the similarity of the neighbours of υ as:

![]() which is the Jaccard similarity of two sets.

which is the Jaccard similarity of two sets.

Let G be a graph of networked machines and entities on the Internet. Typically, we call this an Internet graph if the vertices are made of domains, client machine IPs, hosting IPs, ASNs and registrants. We outline metrics for the machines querying domains, and the domains queried by machines.

We start with υ ∈ V, a machine making queries to other domains. We will derive properties that characterize υ.

For the machine, υ, chattiness is defined as | N(υ) |. This measure defines the breadth of unique domains machine υ reaches out to directly. Further, let the degree of a domain vertex be called the popularity of a domain, i.e. the popularity depicts the breadth of unique machines querying a domain. Then we define the average popularity of domains that machine υ reaches out to as:

μ(ND(υ))

with μ representing the function to compute the mean. Letting m represent the function computing the median, we also compute the median popularity of the neighbours of υ as m(ND(υ)).

We can measure the spread in the popularity of the domains the machine reaches out to with the spread:

![]() If the ratio tends to 1, then υ reaches out to similar domains, i.e. the domains have similar popularity. If the ratio tends to be small, then υ reaches out to more dissimilar domains, i.e. the domains have wider variance in popularity.

If the ratio tends to 1, then υ reaches out to similar domains, i.e. the domains have similar popularity. If the ratio tends to be small, then υ reaches out to more dissimilar domains, i.e. the domains have wider variance in popularity.

The machine, υ, may also query different domains at different times. Given two graphs, Gi and Gi-1, where Gi captures the interactions of machines on the Internet within one time window, i, and Gi-1 captures the interactions in a previous time window, i-1, we can measure the replication factor of machine υ as J(υ). The replication factor measures how much a machine queries the same domains from one time window to another.

In summary, we have the following properties of a machine υ when given two graphs, Gi and Gi-1:

Just as we characterized machines querying domains, we may also characterize the domains queried by machines.

Given a domain, υ, from graphs Gi and Gi-1, we compute the:

where the replication factor measures the proportion of querying machines repeating from one time window to another.

Given a graph Gi holding a snapshot of time, with machines querying hostnames and hosting IPs hosting hostnames, we now translate the graph properties into various signals plotted against time.

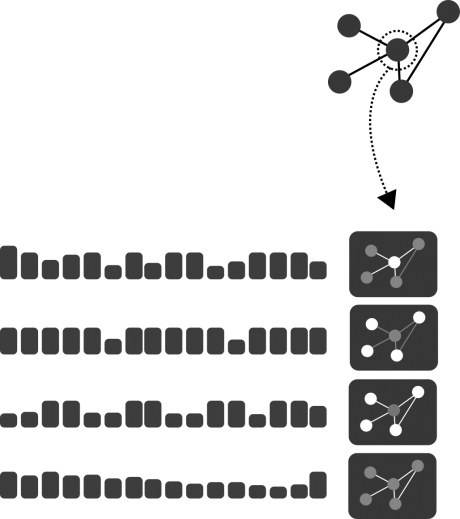

Figure 2: Given a graph Gi, each vertex υ has properties that when stored for subsequent Gi+1 form a time-series.

Figure 2: Given a graph Gi, each vertex υ has properties that when stored for subsequent Gi+1 form a time-series.

Figure 2 shows a graph translated into various signals. In particular, each vertex has properties that can be computed. These properties, once stored and plotted as a sequence, form a signal.

Figure 3 shows a sequence of graphs translated into one graph with signals maintaining the order of the vertex properties at each time step. The signals represent various topological characteristics in two respects: horizontally and vertically in time. For example, vertically refers to one time step where the signals hold all the vertex properties of one corresponding graph, and horizontally refers to a time window (viewing the signals proper) with the signals representing the change in vertex properties from the sequence of graphs.

Figure 3: Given graphs Gi, Gi+1, Gi+2 we can represent the union of graphs in one graph with signals maintaining the order for each vertex property.

Figure 3: Given graphs Gi, Gi+1, Gi+2 we can represent the union of graphs in one graph with signals maintaining the order for each vertex property.

From a sequence of graphs we can now mine the graph for subgraphs. The first subgraph we mine through identifies a cluster of suspicious clients (in terms of their behaviour) where the domains visited by these clients are uniformly suspicious (also in terms of behavioural characteristics). Next, we start from a known list of malicious domains and pivot through the clients to find related domains with similar behavioural characteristics.

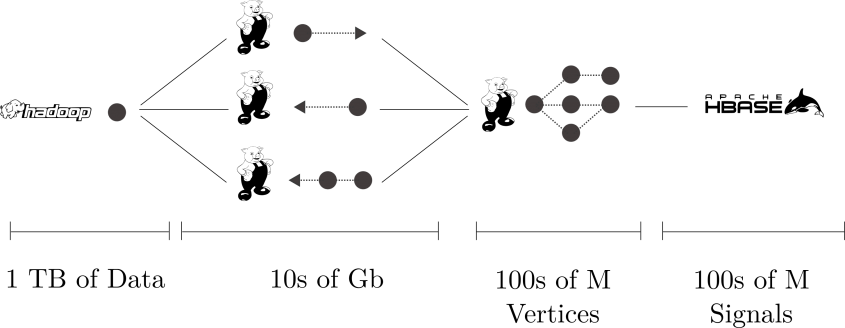

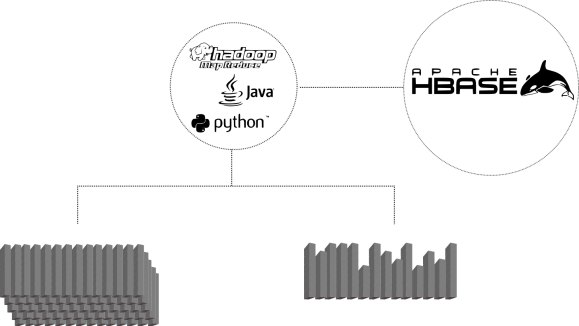

The Hadoop technology stack described here utilizes HDFS, Pig, and Hbase. One may wish to exchange Pig for Scalding or Spark, as desired.

Figure 4 is a diagram of the extract transform layer (ETL) of ingesting logs, transforming, and making them available within the distributed key value store HBase. With this process we manage large-scale graph analytics (millions of vertices, millions of edges) by breaking the process into two steps: 1) merging of various logs for preparation and construction of various graphs, and 2) the traversal and message-passing computations over graph nodes and edges. Each phase feeds into other subroutines in other analytic-pipelines, so we monitor these processes in case the system builds back-pressure.

Figure 4: Diagram of architecture: 1) HDFS: log storage, 2) Pig: graph construction, 3) Pig: computation of graph properties, 4) HBase persist.

Figure 4: Diagram of architecture: 1) HDFS: log storage, 2) Pig: graph construction, 3) Pig: computation of graph properties, 4) HBase persist.

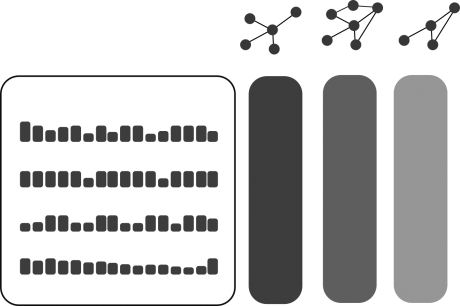

Figure 5 highlights our utilization of HBase for multiple purposes. For example, assuming we have successfully transformed our graph into a set of meaningful signals, we then require the flexibility to scan for individual and groups of signals. The reason for this is that we may want to index various signals for quick searching and clustering, while on the other hand, we may want to analyse and detect patterns within a single signal.

Figure 5: Diagram of typical design pattern interacting and utilizing signals stored in HBase. Left-leaf: bulk aggregate and correlations of signal (indexing, clustering); right-leaf: individual signal uses (R&D, UI).

While the algorithmically generated domains (AGDs) of Necurs, Pykspa and Conficker are well studied, there is no comparable study in behavioural attributes. Using the signals from the bipartite graphs we are now in a position to characterize the traffic to these AGDs and from the client machines querying AGDs. In other words, for example, we can uncover how popular an AGD is and how chatty a client machine might be. In short, bot-like machines uncover botnet domains.

An infected client machine querying AGDs may query different domains from one time period to the next. Figure 6 is an example of one machine querying seven different domains in four different time intervals. In this figure, we notice the machine queries at least three domains per time period and queries the same domain in consecutive hours at least once (though not the same domain every hour). In other words, this is an example of a client with a chattiness signal of [3,4,3,4] and a replication signal of [1/2,2/3,1/2,2/3].

Figure 6: One machine querying seven domains at four different time intervals.

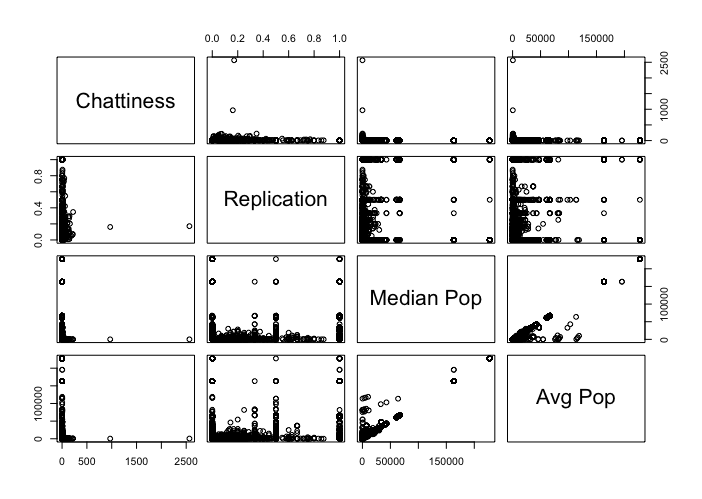

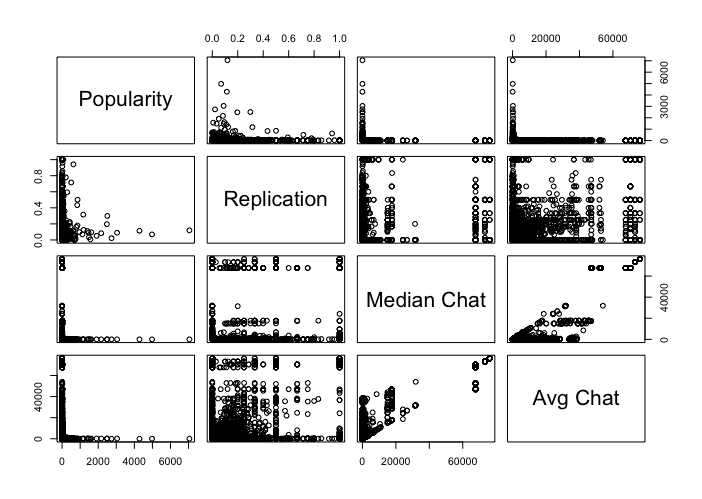

We wish to identify suspicious or infected clients, ensuring that the resulting domains they visit are possibly related to a botnet. To that end, we take a snapshot of the graph properties related to clients from one time period in a scatterplot of chattiness, replication, median popularity and average popularity. The goal is to identify clusters within the 2-D projections identifying clients with predictable behaviour.

Figure 7 is the resulting scatterplot on a sample of 10,000 clients from 1.4 million clients corresponding to a one-hour snapshot. Note that the scatterplot captures a few intuitive hypotheses about the behaviour of an infected machine. For example, if the chattiness of a machine increases by one, is there a linear relationship with replication? In other words, is a machine that queries one more domain than another likely to have a higher replication factor? Or another: does the median popularity of domains queried by a machine correlate with the average popularity? That is, if a machine queries domains resulting in a low median popularity (i.e. the machine queries low popularity domains about 50% of the time) are they just as likely to query highly popular domains, resulting in higher average popularity?

Figure 7: Scatterplot of client statistics from a sample of 10,000 out of 3 million clients.

Figure 7: Scatterplot of client statistics from a sample of 10,000 out of 3 million clients.

Figure 8: 168 hours with five-hour window boxplots of 183 clients flagged in the most recent window (far right) for having popularity greater than 100, replication greater than .50, and median and average popularity spread less than 1.1.

Figure 8: 168 hours with five-hour window boxplots of 183 clients flagged in the most recent window (far right) for having popularity greater than 100, replication greater than .50, and median and average popularity spread less than 1.1.

Following questions like those posed above, we hypothesized that clients resulting in a high replication (above .50) and a spread in median-to-average popularity of domains (within 10%) ensured clients visiting botnet domains. In other words, these clients were showing bot-like behaviour by visiting domains with basically the same popularity from hour to hour (and even the same domains at least 50% of the time). Figure 8 is a sample of 183 clients flagged with having a replication factor greater than 0.30 and spread within 10%. From our experiments we have found 100+ clients (per hour). These clients appear largely consumed with querying Conficker, Pyskspa, Suppobox, and some unknown botnets.

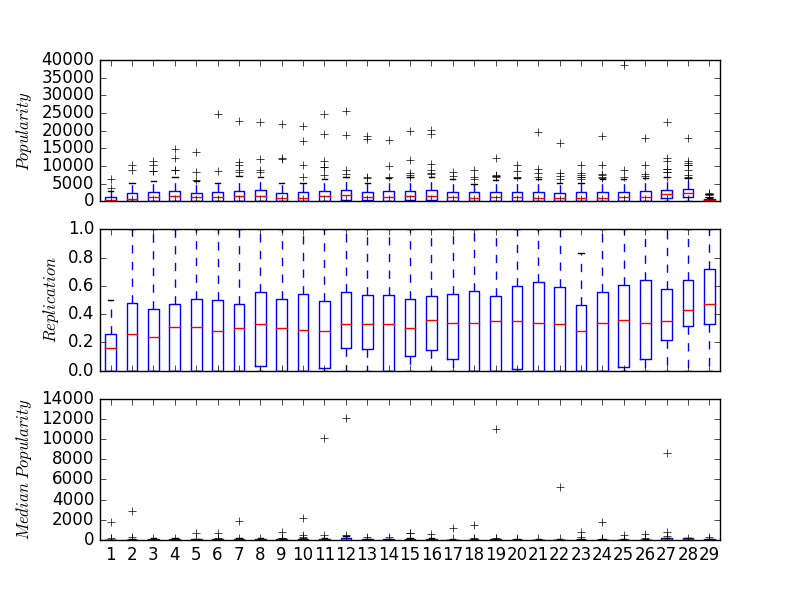

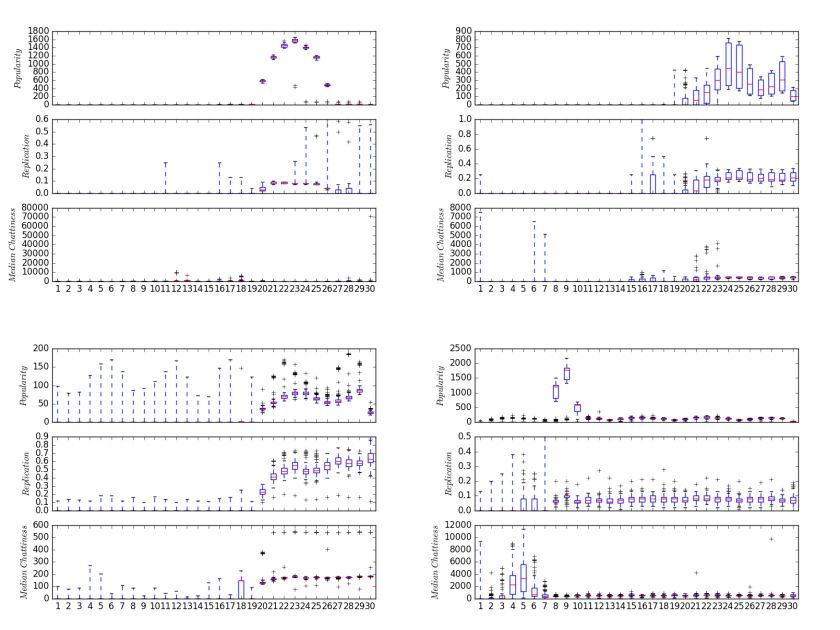

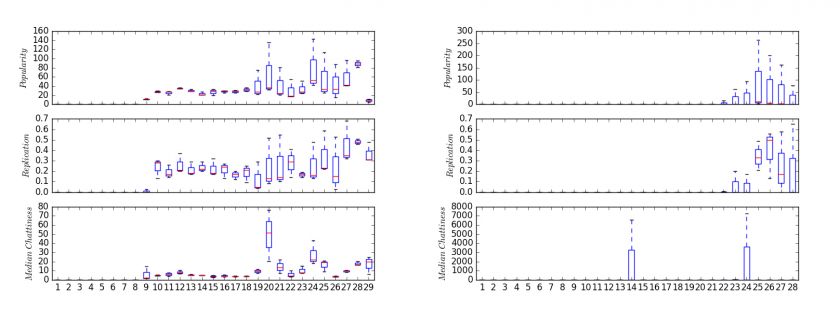

In Figure 9, we visualize four families of domains flagged from bot-like clients over three days rolled into two-hour intervals (the right side the most recent, the left the earliest day). Refer to Appendix A for a sample of the domains.

Figure 9: Four families of botnet domains found from bot-like clients. Top left: domains attributed to the Conficker botnet. Top right: domains attributed to the Suppobox botnet. Bottom left: domains attributed to an unknown botnet. Bottom right: domains attributed to the Necurs botnet.

Figure 9: Four families of botnet domains found from bot-like clients. Top left: domains attributed to the Conficker botnet. Top right: domains attributed to the Suppobox botnet. Bottom left: domains attributed to an unknown botnet. Bottom right: domains attributed to the Necurs botnet.

The signals are the popularity and replication of the domains and median chattiness of the clients querying the domains. Note that each family is easily differentiated from the others: Conficker, Necurs, Suppobox, and one unknown botnet. The boxplots aggregate the individual signals per domain identified within a family. Conficker is made of 205 domains; Necurs 41 domains; Suppobox 81 domains; unknown botnet 139 domains.

Interpretation of Figure 9: Conficker is characterized by a uniform spike over a 12+ hour spike in popularity reaching 1,600 machines. In addition, we see the replication interquartile range tighten during the spike around 0.10.

Suppobox, on the other hand, appears to have spiking periodic activity with popularity ranging between 100 and 800 machines. Furthermore, as the popularity reaches the first peak in periodicity the replication tightens around 0.20 to 0.40 and in fact appears steady and not periodic (at least not as extreme as popularity). The unknown botnet appears to have the widest variance in popularity leading into the period of sustained activity from multiple bot-like machines ranging from 50 - 100 machines. At the climax of popularity, the replication trends between 0.40 and 0.60 (reaching the highest replication ranges of the four families). Lastly, Necurs is characterized by a three-day sustained popularity below 500, except for an exaggerated spike of up to 2,000 machines querying the domains, and the replication tightens after the spike of 1,000+ machines around 0.10 along with the median chattiness.

In the previous section we used the signals from the sequence of bipartite graphs to flag bot-like clients and identify families of domains with similar popularity, replication, and median chattiness. This approach relied on identifying suspicious clients to find botnet domains. Another approach is to start from known botnet domains and find other related domains. Related to this are techniques in belief propagation. Using the signals derived from the sequence of bipartite graphs we can identify similar domains based on machine querying behaviour.

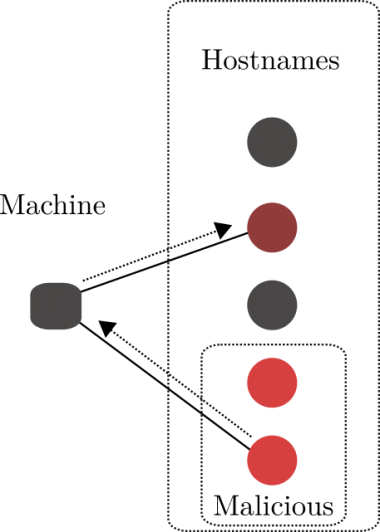

Figure 10 shows one machine querying two domains within a time interval. One domain is known to be malicious, and we would like a technique to identify whether the other domain is also malicious. Note that we are simply asking if two vertices that co-occur (or are queried) from the same client are similar, in other words: are the signals related to each domain similar to one another? As seen in the previous section, we suspect that the signals: popularity, replication, and median chattiness, can be used to find related domains. To formalize things, the goal is to identify clusters within the 2-D projections identifying domains.

Figure 10: From a seed of malicious domains, pivot from querying machines to other domains queried.

Figure 10: From a seed of malicious domains, pivot from querying machines to other domains queried.

Figure 11 is the resulting scatterplot on a sample of 10,000 domains from 6.4 million domains corresponding to a one-hour snapshot. Note that the scatterplot captures a few intuitive hypotheses about the behaviour of domains that might be similar to one another. Perhaps the easiest is to try to identify domains being queried by bot-like machines. That is, one might look for domains with (about) equal median and average chattiness of the clients. To that end, we try to identify clusters along the diagonal of the median and average chattiness scatterplot. Now, just test whether the domain has high or low replication of clients. Further, one might test the hypothesis: replication is correlated to popularity. Or more simply, suppose a domain has a replication factor of 0.20 and a popularity of 1,000. Is a domain with a replication 0.20 and a popularity of 5,000 more common?

Figure 11: Scatterplot of domain statistics from a sample of 10,000.

Figure 11: Scatterplot of domain statistics from a sample of 10,000.

Following questions like those posed above, we hypothesized that similar domains clustered based on the signals: popularity, replication, and median chattiness yield homogeneous clusters. These clusters we hoped would contain one family of botnet domains (and no false positives). We conducted this experiment using the popular Bambenek DGA feed containing 403,644 domains. In testing we found an average of 19,000 domains queried by machines, hourly.

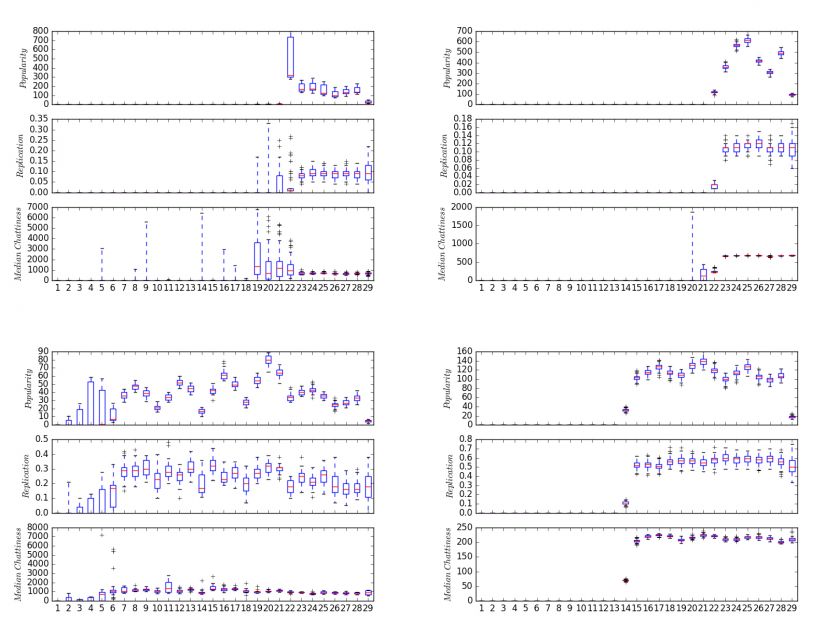

In Figure 12, we visualize three families of Bambenek domains and the fourth is a family of domains found by pivoting off Bambenek domains (without a single domain flagged by Bambenek). Refer to Appendix B for examples of the domains. The time interval is from a span of 168 hours rolled up into six-hour windows (the right side the most recent, the left the earliest day). The signals are the popularity and replication of the domains, and median chattiness of the clients querying the domains. Note that each botnet is not necessarily differentiated from the others in terms of lexical content (but the traffic patterns are): Necurs 1, Necurs 2, Pushdo, and one unknown botnet. The boxplots aggregate the individual signals per domain identified within a family. Necurs 1 is made of 82 domains; Necurs 2 107 domains; Pushdo 29 domains; unknown botnet 211 domains.

Figure 12: Four examples of domains related to botnets. Top left: domains attributed to the Necurs botnet. Top right: domains attributed to the Necurs botnet (with a different traffic pattern). Bottom left: domains attributed to the Pushdo botnet. Bottom right: domains attributed to an unknown botnet.

Figure 12: Four examples of domains related to botnets. Top left: domains attributed to the Necurs botnet. Top right: domains attributed to the Necurs botnet (with a different traffic pattern). Bottom left: domains attributed to the Pushdo botnet. Bottom right: domains attributed to an unknown botnet.

Interpretation of Figure 12: Necurs 1 is characterized by one spike over a six-hour window with popularity reaching 700 machines. In addition, we see the replication interquartile range tighten after the spike around 0.10. Necurs 2, on the other hand, appears to have spiking periodic activity with popularity ranging between 100 and 700 machines. In addition, as the popularity reaches the first peak in periodicity, the replication tightens around 0.12 and in fact appears as steady as the median chattiness between 500 and 1000 domains. The Pushdo botnet appears to have the longest period of activity, spanning almost the entire 168 hours. In addition, the popularity ranges from 10 to 80 machines along with the replication between 0.10 and 0.40. Lastly, the unknown botnet domains are characterized by a spike in popularity trending between 100 - 140 along with an almost uniform replication around 0.60 and median chattiness of 200.

In the previous section we used the signals from the sequence of bipartite graphs to cluster domains with similar signals from a set of known malicious domains. We provided initial clusters based on the co-occurring domains from client machines querying the malicious domains and refined those based on the families of signals. We now extend this idea by starting from a set of malicious hosting IPs.

Figure 13 is an example of a known malicious hosting IP with one domain resolving to it. With the assumption of any domain resolving to this malicious hosting IP, we can apply the methods described in the previous section. That is, traverse the graph and gather the co-occurring domains reachable through the clients querying the domain hosted on the malicious IP. Further, this hosting IP may have multiple domains resolving to it, and in a similar fashion, we gather the co-occurring domains (from clients) to those domains.

Figure 13: One machine querying seven domains at four different time intervals.

Figure 13: One machine querying seven domains at four different time intervals.

In Figure 14, we visualize three Zbot domains resolving to the same hosting IP. We call Zbot domains any malware domains that are using the Zbot fast flux proxy infrastructure as described in [13, 14, 15], therefore these domains could belong to either one or many different malware families but in our study they share similar traffic patterns. Refer to Appendix C for examples of the domains (including previous domains studied but not reported here). The time interval, as before, is from a span of 168 hours rolled up into six-hour windows (the right side the most recent, the left the earliest day). The signals are the popularity and replication of the domains, and median chattiness of the clients querying the domains. The boxplots aggregate the individual signals within the six-hour windows.

Figure 14: (Left) Three Zbot domains resolving to some of the same fast-flux IPs. (Right) Three Zbot domains resolving to similar fast-flux IPs, but caught early in the campaign. These domains exhibit similar popularity, replication, and median chattiness.

Figure 14: (Left) Three Zbot domains resolving to some of the same fast-flux IPs. (Right) Three Zbot domains resolving to similar fast-flux IPs, but caught early in the campaign. These domains exhibit similar popularity, replication, and median chattiness.

Interpretation of Figure 14: These three Zbot domains open the campaign around the same time: the ninth timestep on the x-axis. The three Zbot domains synchronize over the next 10 timesteps before beginning to diverge. In particular, these campaigns opened with around 20 client machines querying each domain with a replication factor between 0.20 and 0.30. In other words, up to six client machines queried the same domain from one hour to the next.

Furthermore, these client machines were simultaneously querying roughly 10 other domains for the opening portion of the campaign.

In Sections 8, 9 and 10, we examined cohorts of domains which cluster together with waveforms produced in the popularity, replication, and median chattiness of the domains. There are a variety of comparisons that can be made between the signals but one stands out: the tight bound in median chattiness appearing in every family of botnet domain (at some point in the campaign) from Necurs to Zbot. Table 1 is a breakdown of the values of each signal during one time window per botnet.

| Botnet family | Median chattiness | Replication | Popularity | Popularity / Replication |

| Zbot | 10 | .20 | 40 | 40/.2 = 200 |

| Necurs | 1 | .10 | 200 | 200/.1 = 2000 |

| Pushdo | 1000 | .20 | 60 | 60/.2 = 300 |

| Suppobox | 500 | .3 | 300 | 300/.3 = 1000 |

Table 1: Approximate values within time windows from Zbot, Necurs 1, Pushdo, and Suppobox from Figures 9, 12, 14, alongside the ratio of popularity / replication.

In Table 1, we begin by breaking down the median chattiness across four botnet families. These values were pulled from a portion of the campaign where the median chattiness boxplots appeared most uniform. In other words, 50% or more of the clients querying these botnet domains were querying about this many other domains. For example, a given Zbot domain may have had 40 client machines query it, while those machines were querying (roughly) 10 other domains. Now, suppose we make a big assumption: that all 10 domains are also Zbot domains. That's one guess for how many domains are within this campaign.

More generally, one might say that when a domain's median chattiness gets tight, then the numbers where the band hovers is the number of domains that might be in a botnet (for a specific campaign). Consider, on the other hand, 40 clients querying 10 other domains in one time window, then in the next window they query 10 but only repeat 20%. Further, in the next time window assume the clients (in the median) query 10 other domains. Then one would suspect 10(1.8) = 18 domains in the botnet. Therefore we suspect that the value:

Median-chattiness * (1 + 1 - replication-of-clients)1

provides an approximate number of domains within a campaign of the botnets studied herein.

(1Actually this might really be: mc ( (1-r) + (1-r) r + (1- r) r^2 +......). With r = replication of clients and mc = median chattiness.)

In this paper we introduced the notion of a tripartite graph modelling the relationships of client machines querying hostnames along with those hostnames hosted on an IP. We described various vertex properties and formed signals from a sequence of tripartite graphs. We then induced three types of subgraphs: client-to-domains, domains-to-domains, and hosting IPs-to-domains. From each induced subgraph we studied cohorts of domains clustering together with similar signals: popularity, replication, and median chattiness of the clients. Finally, we outlined a method to predict the number of domains per campaign underway in a botnet by using the median chattiness and the replication of clients which can be found during the tightest period of median chattiness during the campaign.

[1] Khalil, I.; Yu, T.; Guan, B. 2016. Discovering Malicious Domains through Passive DNS Data Graph Analysis. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security (ASIA CCS '16). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 663-674. https://doi.org/10.1145/2897845.2897877.

[2] DGArchive: A deep dive into domain generating malware. Botconf 2015. https://www.botconf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/OK-P06-Plohmann-DGArchive.pdf.

[3] Hong, L. DNS Traffic Analysis for Network-based Malware Detection. Technical University of Denmark Informatics and Mathematical Modelling.

[4] Krmıcekm V. Inspecting DNS Flow Traffic for Purposes of Botnet Detection. GEANT3 JRA2 T4 Internal Deliverable. 2011.

[5] Shuman, D. I.; Narang, S. K.; Frossard, P.; Ortega, A.; Vandergheynst, P. The emerging field of signal processing on graphs: Extending high-dimensional data analysis to networks and other irregular domains. In IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 83-98, May 2013.

[6] From Throw-Away Traffic to Bots: Detecting the Rise of DGA-Based Malware. Usenix 2012. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/usenixsecurity12/sec12-final127.pdf.

[7] Phoenix: DGA-Based Botnet Tracking and Intelligence. DIMVA 2014. http://www.syssec-project.eu/m/page-media/3/schiavoni-dimva14-phoenix.pdf.

[8] A Comprehensive Measurement Study of Domain Generating Malware. Usenix 2016. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/usenixsecurity16/sec16_paper_plohmann.pdf.

[9] Malpedia. ACSC 2017. http://pnx.tf/slides/2017-03-16-ACSC-Malpedia.pdf.

[10] Yadav, S.; Reddy, A. K. K.; Reddy, A. N.; Ranjan, S. Detecting algorithmically generated malicious domain names. In Proceedings of the 10th annual Conference on Internet Measurement, IMC '10, pages 48–61, New York, NY, USA, 2010. ACM. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0781/d1e2c2027794393eb33cc08d60fff2940c32.pdf.

[11] Yadav, S.; Reddy, A.L.N. Winning with DNS failures: Strategies for faster botnet detection. In: Rajarajan, M.; Piper, F.,;Wang, H.; Kesidis, G. (eds.) SecureComm 2011. LNICST, vol. 96, pp. 446–459. Springer, Heidelberg (2012). http://cesg.tamu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/reddy_papers/securecomm11.pdf.

[12] Passerini, E.; Paleari, R.; Martignoni, L.;Bruschi, D. fluXOR: Detecting and monitoring fast-flux service networks. In: Zamboni, D. (ed.) DIMVA 2008. LNCS, vol. 5137, pp. 186–206. Springer, Heidelberg (2008). http://roberto.greyhats.it/pubs/dimva08-fluxor.pdf.

[13] Mahjoub, D.; Sakaly, M.; Mathew, T. Towards a Holistic Approach in Building Intelligence to Fight Crimeware. Black Hat 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hBzGM3d7c1Y&t=3s.

[14] Mahjoub, D. A New Look at Fast Flux Proxy Networks. BotConf 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eC2jPNU0NZI.

[15] Mahjoub, D.; Reuille, T.; Toonk, A. Catching Malware En Masse: DNS and IP Style. BlackHat 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cHuyqnVhT4g&t=4s.

| Conficker | Suppobox |

| asguyisxag.cn dhkbnigbmk.cn ikibb.cn qofzsoukgv.cn bwrxituu.cn ldjeg.cn lmdyzeaec.cn vowncqnmrg.cn awqmmbmales.cn civcsuxik.cn tfyiar.cn pbwrgxap.cn lsqccdepmsj.cn kbxqlrfsejf.cn ouatgvfu.cn rmxyfdfqiet.cn hyxvo.cn mifdrrhjj.cn xzkfu.cn mrfalvan.cn lrydsjjvenl.cn tjumdjii.cn vnsmvolq.cn afhsyl.cn itnloxsbxts.cn |

nonelose.ru silvestercharisse.ru outsidetwenty.ru desirealmost.ru grosvenorcassarah.ru callfull.ru grenvilleunderhill.ru celandineharrison.ru eveningalmost.ru pointdaily.ru leadlose.ru annabellaannabeth.ru silvestercassarah.ru doublemeeting.ru fellowreason.ru nosehave.ru geraldineviviette.ru eveningunderstood.ru fiftythere.ru liarocean.ru thomasinaannabeth.ru grenvilleannabeth.ru deforrestfairbairn.ru jeffersonangelica.ru tableblood.ru |

| Unknown | Necurs |

| vpcvcixgcdlkoj9k.com pbjsbaowcpzsy27.com kztfyzewgqajp.com mzeauuaajr2q.com zrbvdesbkydudhbibu.com kbzjyxayhqiediyksg.com ehjsowotiimskejrrb.com tsugycannnpbm4a.com wnfsoaumsjad.com pegzasrdqdejixsp.com vtpfiacctyyzs.com amelzudthrhl4.com wrkecvplwobtkataii.com pjuqivrgzccwma75.com mdsozfmhhponvjudf8.com wzadnytpuxsa7x.com rzfqpzfngokjox.com athapsmjpmiby.com wsdojxxzkornvjs.com htpvayktihpckppr.com zyqzaegunhxqihv.com umcnzpswuzzohaue.com gzmdgbqhgxvwufr4g.com t7uiefn.com scqsrrykltxf.com |

cfcuarw.sh fmgfrjg.in otwzgnl.ru ovdeusk.ga wcnsxdo.jp ybeklgt.eu ybrlhpe.ru agrtwgch.cx dixpbqbi.ru fjmppybw.ru fvdfneeo.mu kknhqcra.mn okxkyxwp.ru qfhdjzru.ru rjbkkxxb.ru vkauhpr.biz wqssublx.ru wyavcujm.jp yfyddgbp.ru anxtygnqt.jp bjzdpfnx.net csdmsoesq.so dqgiwjbww.ru ermnuewsf.cm hwcookvfx.tv |

| Necurs 1 | Necurs 2 |

| gnmjgxxademtgpetqt.sc kvffqiryrnmmghumbjj.ac tchpelfjbcvaepfqtopg.biz augwnsyhfjdqrh.jp ieqdtejtjyp.tv bpqmwruwvpy.net fdhftximvov.so osmanppvqlpoflofgjss.org imtraimjurxjijc.pw dafgmvkqtglgcfohpiift.tv cqwecshovxeowohj.ki pbwbociwujrisgooja.ki pqbflmdnedx.de sdwryvuuokccl.tw ncmhltjkxdkudgenvi.sx wyyfnipawohvawibeoui.im ivdvacqghsaokxx.tj eojupecjddnviwkf.ms ypqvsotunfjcwgmqw.eu uuiyuedjcgqrkiikhv.org lsqbkcvtur.ac kqvjrivjesbouh.bz ctsdnrjgk.xxx sngdykmymoevcxvqll.jp hgxgehw.xxx |

knlvsgbbfgbf.to dwfdphkcw.to evmbfvndebnwggw.to wbvwbxqqbjurk.to yqykqrrtlyk.to tvijoqfswt.to yqshpwfbpvpkpvua.to fxxptjsaqxcyqwbnot.to joprxxwgmalu.tv iexsqafpkfuihkhrnul.cm ppksiqnpbkssl.jp gfnvqawqmvntruwof.mu rmldddayyoyacffqfavu.la obntrhqbnvuysjlt.bz vtiwqtky.sc tvkrsyubm.pro guyjfjldpla.org qsqrqvukpj.us srpnbdwjvyh.ug npncalhipo.biz cyvbkdtuqrrrpk.nf tkaxmvotugtnfjkud.mu yhldewlfpgpppnpmqvovx.im sjawwmfddnk.us bwfbswhhgi.la |

| Pushdo | Unknown |

| syiwesxacaft.kz felfobhuw.kz qovokluctuc.kz mophezazqu.kz lohyikesjobg.kz sazcuworu.kz zyijucbymdyi.kz dyiluvokca.kz lyodohyazesd.kz fazloprago.kz seskokvoce.kz goklevafg.kz cyogunkaffob.kz heqobperxop.kz jyasazxefob.kz pybeguqkulyi.kz tyxcerxamo.kz bafkatkafr.kz bazalahazqa.kz qyirygkuz.kz qobqathoza.kz jopuqrobaft.kz vesgyodeg.kz felfawunc.kz tymrerdyi.kz |

vwylysndkjo0y.com huujizqvufbfdohm.com dgschrsnyexof0.com dmuwmmmnpqsovsvx38.com bcjcrojblzrdb2t.com uxzhmwdytpcf.com nhftqdtghebojkw5.com ukntgygowex9v.com zhwdijnnfgnuncwx8o.com oxmxvchmwlajmejx5t.com zyiisphakabfd.com qfjlpbxemhkk.com eboknjldedmyzgux4q.com kpdzrzjkwcil15.com bbnlagrdxvlyqo2p.com bwoqewtpeduwc.com mcpayabijhm8.com oukcdqumruqna3x.com zjhpdenbhkfbdc.com umpkalafubo5c.com vtsucwihjeravngta.com msoweikrwiqdnzsnzh.com raslqtgdgvrxyitv.com qtbktidrtlxdbl.com emvyjkkghfvupbh.com |

| Zbot | |

| Figure 14 (left) | availablethislictwarra.ru contributionscoveredphp.ru frfortonotanygroupname.ru |

| Figure 14 (right) | coveredcontinuecalphp.ru promisnenssas.net providedsuchdistribution.ru |

| contributionscoveredphp.ru point.bitsinc.org promishlenniewas.net bvcgos.com ardshinbank.at |

|

| areysoftwaretthewarra.ru anddistributionineither.ru ytheotherbinathefitness.ru faoriginalclausemayawnon.ru disclprodyousaid.ru filesotherincludeother.ru notwarrantiessaid.ru |