Malwarebytes, Canada

Copyright © 2018 Virus Bulletin

The web threat landscape has changed drastically over the past few years due to a decline in exploit kit activity. Faced with a shift in browser market share and built-in exploit protection within the operating system, attackers have had to resort to other techniques to turn a quick profit.

Meanwhile, cryptocurrencies have soared to high levels, driven by the dramatic rise in the value of Bitcoin. In addition, new forms of cryptocurrency, such as Monero, have gained rapid momentum and have become popular for allowing mining using average consumer PCs.

When a new API came out that allowed cryptomining to be run directly within the web browser, a new El Dorado, ripe for abuse, was created overnight. We are referring to the phenomenon known as in-browser mining or drive-by mining, where visitors to a website unknowingly mine for cryptocurrencies in a completely automated way without their consent or that of the site’s owner, ultimately benefiting criminals.

In this paper we will look at:

We conclude this paper by examining the legal aspects of in-browser mining and its business model as a possible replacement for traditional ad banners.

When it comes to web threats, the perfect attack scenario is one in which the victim does nothing out of the ordinary and is compromised seamlessly. For example, they could simply be browsing various websites and get infected. For years, exploit kits have been used to leverage vulnerabilities in client-side software (a browser or a plug-in) to deliver malware.

However, the increasing interest in cryptocurrencies, along with new in-browser mining techniques and proof-of-work algorithms, has changed things. Indeed, criminals no longer need to exploit vulnerabilities or push malware in order to generate a profit.

As we will see in the following section, browser-based exploitation has become less effective in recent times, which has forced online criminals to adapt.

Exploit kits have been one of attackers’ favourite means to distribute malware over the years thanks to a constant supply of new vulnerabilities (and often zero-days [1]) being added to their arsenal. Since most users do not patch their systems on a regular basis, exploiting those vulnerabilities was one of the easiest ways to deliver payloads on a massive scale.

Angler was considered by many to be one of the most prolific and advanced exploit kits that ever existed, after having succeeded Blackhole, another toolkit that, for years, was the king of the drive-by landscape (until its author was arrested [2]).

Angler was part of many different attack chains and distributed a variety of payloads, even using fileless techniques, along with its sidekick, Bedep [3]. The constant innovation spearheaded by the group behind Angler created a competitive dynamic with other exploit kits and resulted in drive-by downloads becoming the primary infection vector, well ahead of other attack vectors, such as malicious spam.

However, everything changed when Angler completely vanished in June 2016 [4], its disappearance likely to have been correlated to the arrest of members of the Lurk gang [5]. While the ensuing void could have opened up the playing field for others to take over, the opposite happened. Over the next few months, long‑standing exploit kits such as Neutrino and Magnitude switched into private mode, and their activity either diminished or was restricted to a particular geographic location.

Also noteworthy is the fact that the remaining actors did not actively seek out new vulnerabilities to integrate into their toolkits (unless they were provided on a silver platter – via proof of concepts [6], for instance). As exploits start to age, the efficacy of exploit kits diminishes accordingly. This turns into a vicious cycle where threat actors are not happy about not getting their ‘loads’ and resort to other delivery methods to get the job done.

In the first half of 2018, RIG and GrandSoft were two non‑geographically limited exploit kits that were still fairly active, almost entirely via malvertising campaigns. Interestingly, common payloads have often included cryptominers [7], usually via the intermediary of SmokeLoader.

As the browser market share for Internet Explorer continues to decrease and the most exploited plug‑ins are becoming less popular or phased out, the impact of exploit kits as a global threat is being called into question.

We noticed a shift towards exploits packaged within Microsoft Office documents, for example with Flash [8] and VBScript engine [9] zero-days, before they were eventually adopted in browser exploit kits.

In more recent years, document-based exploit kits such as Microsoft Word Intruder (MWI) [10] and ThreadKit [11] have become hot commodities and moved from targeted attacks to the more common malspam waves. Similar to their browser counterparts, attackers using these kits have the ability to pick and choose which vulnerabilities to include in the custom Office file they intend on sending to their victims, as well as to track the success of their campaigns.

It is well known that social engineering in its various forms remains an effective means of compromising end-users. By leveraging existing delivery channels such as hacked sites and malvertising, criminals have come up with clever ruses to trick people into installing fake fonts [12], browser updates [13], and anything in between.

To understand to what degree threat actors have adopted social engineering schemes in favour of exploit kits, we can take the example of the group behind the Kovter ad fraud malware. For years, it relied on different exploit kits such as Sweet Orange, Nuclear and Angler [14], but eventually it turned to fake font updates pushed via high-profile malvertising campaigns [15].

While social engineering combined with malicious traffic campaigns will remain highly prevalent, the same may not be true for drive-by downloads, even if in the first half of 2018 new zero-days temporarily gave exploit kits a boost.

In the meantime, the drive-by threat landscape has seen the emergence of a new way for criminals to make money without relying on user input: silently loading cryptomining APIs.

Cryptocurrencies are decentralized digital assets produced by mining, a process-intensive operation that adds transaction records to a public ledger called the blockchain.

Over the last few years, cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin have gained attention not only for their increased value, but also for their extreme volatility. An amusing example (for everyone but the individual involved) is the case of the Bitcoin pizza: in 2010 an early Bitcoin developer bought a couple of pizzas for 10,000 Bitcoins [16] – a price that, in today’s value, equates to several million dollars [17].

Similar to a gold rush, individuals and companies began investing millions of dollars into building mining rigs that could solve increasingly difficult calculations to be rewarded with new cryptocurrencies. The hardware requirements for mining jumped from regular CPUs to more expensive GPUs and ASICs, whose hash rates set them apart from non‑professional miners.

However, since then, other cryptocurrencies have emerged that level the playing field by making mining inefficient with top‑level hardware, while being optimized for average computers. This is the case for Monero, which has been adopted as the de facto cryptocurrency for mining using the CryptoNight [18] proof-of-work algorithm, specifically unsuited for anything but CPU mining.

In addition to this notable advantage, Monero has also benefited from an increase in value and is said to offer more anonymity [19] than Bitcoin.

In mid-September 2017, a little-known company, Coinhive, came out with an API to make mining within a web browser seamless. The simple code snippet would allow site owners to monetize their traffic by leveraging their visitors’ CPUs to mine for Monero while they spent time on a page.

<script src="https://coinhive[.]com/lib/coinhive.min.js">

</script>

<script>

var miner = new CoinHive.User('SITE_KEY', 'john-doe');

miner.start();

</script>

Figure 1: Coinhive’s JavaScript API (the domain has been sanitized).

Coinhive uses a WebAssembly module to mine at 65 per cent of the performance of a native miner, thanks to a technology [20] available in all modern browsers, while older browsers such as Internet Explorer can still run a JavaScript-based web miner (asm.js) [21]. According to Coinhive, an Intel i7 CPU has a hashrate of about 90h/s.

Coinhive’s payouts are calculated on each solved hash and according to the network’s mining difficulty. From the average block rewards, users are compensated with 70 per cent of the Monero that has been earned, while the rest goes to Coinhive.

The in-browser mining concept was not new at all; in fact, several attempts had been made before, but without much success, in part due to lower performance compared to desktop‑run miners. In one particular case, a group of MIT undergraduates trying to propose an alternative to online advertising even got into legal trouble [22] for their effort.

The timing with the interest in cryptocurrencies, Monero’s growing popularity, and the ease of use of the Coinhive API are some of the reasons why it became an immediate success.

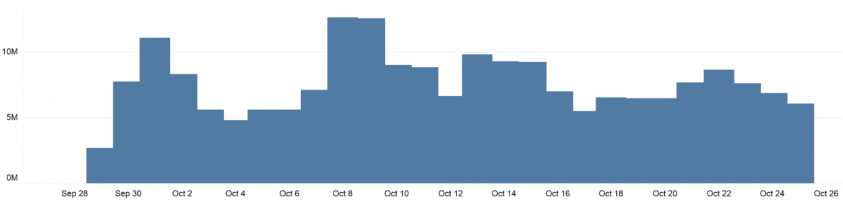

Malwarebytes detected an average of 8 million daily connection attempts to Coinhive from late September to late October 2017 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Malwarebytes detected an average of 8 million daily connection attempts to Coinhive from late September to late October 2017.

Figure 2: Malwarebytes detected an average of 8 million daily connection attempts to Coinhive from late September to late October 2017.

Unfortunately, malicious actors also took note and started abusing Coinhive early on – in large part due to a lack of safeguards built into the API. Indeed, Coinhive could be used in a silent manner without notification or consent, leaving visitors to a site none the wiser that their CPU was being taxed.

In mid-September 2017, just days after Coinhive had become well known, the WordPress and Magento websites [23] were already being injected with malicious Coinhive web miners, even reusing an old infection vector. It became obvious that threat actors had been watching the development of in-browser mining carefully and were eager to start monetizing their compromised hosts.

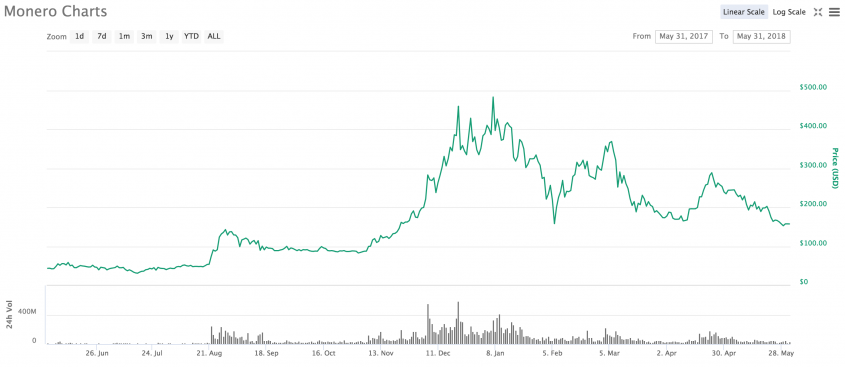

Despite this negative attention, Coinhive’s success inspired several copycats such as Crypto-Loot, Coin Have, and many others, while the value of Monero was about to increase fivefold in December 2017 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The value of Monero.

Figure 3: The value of Monero.

There are many terms that define this new phenomenon, such as ‘in-browser mining’ [24], or the media-friendly term ‘cryptojacking’ [25]. Throughout this paper, we will use the term ‘in-browser mining’ but also sometimes refer to it as ‘drive-by mining’ due to its malicious usage. When talking specifically about code implemented to run within the browser, we will adopt the term ‘web miner’ [26].

We define drive-by mining as an automated, silent, and platform‑agnostic technique that forces visitors to a website to mine for cryptocurrency. This excludes web miners embedded within a browser extension [27] or loaded by adware [28].

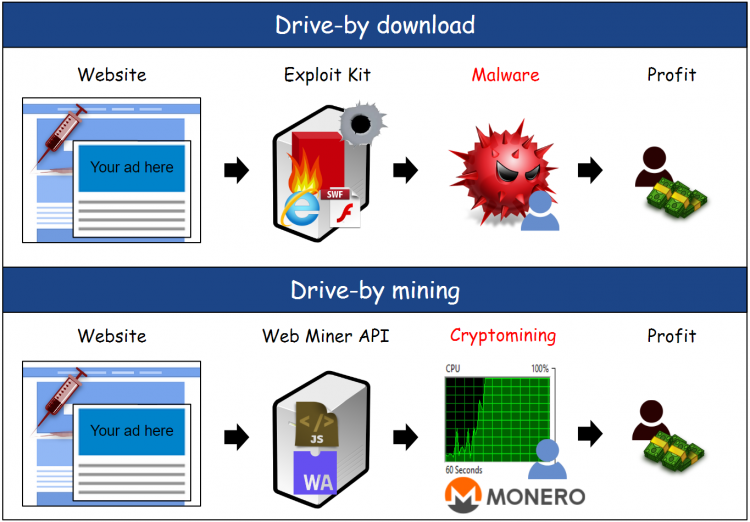

This technique reminds us of drive-by downloads, except it’s even easier to ensnare victims because it does not require any kind of vulnerability to be exploited and can run on any modern browser and operating system.

Figure 4: Drive-by download vs. drive-by mining.

Figure 4: Drive-by download vs. drive-by mining.

It is important to differentiate legitimate cryptomining from its criminal uses. One of the key aspects of drive-by mining is the lack of user acknowledgement often to push the victim’s CPU to 100 per cent of its capacity.

Ironically, the majority of forced mining also involves a lack of awareness from the site owners whose infrastructure is used as a distribution and spreading mechanism.

There are many similarities between drive-by mining and drive-by download campaigns in terms of delivery mechanism and affected entities.

During the past several months, we have seen high-profile cases of malicious cryptomining on large portals, government websites, and the ever-growing pool of hacked Content Management Systems (CMS).

Early adopters of web miners were torrent portals, such as The Pirate Bay (Figure 5), which was considered to be an important backer and which accidentally set a milestone for unwanted cryptomining. As an experiment for ad replacement, the site administrators decided to run Coinhive but failed to disclose their intentions to their loyal user base, many of whom were annoyed at finding their CPU maxed out without warning [29].

Torrent portals and streaming sites that drive a large amount of traffic were the most likely to generate a substantial income via Coinhive’s API, even though the gains ended up being insignificant [30].

The Pirate Bay ‘incident’ also inadvertently generated publicity for the Coinhive service that went on to gain traction on shady portals, often via malicious ads already generating malicious redirections [31]. What could have been a legitimate alternative to online advertising was quickly turned into an additional revenue stream, sometimes on top of regular advertisements.

Incidentally, malvertising is a practical delivery mechanism for more than just malicious redirections and exploits, in that web miners can be loaded seamlessly, without requiring any sort of client-side infection. A high-profile malvertising campaign ran on YouTube because a rogue advertiser [32] managed to subvert Google’s DoubleClick and push Coinhive code within the bogus ad banner.

Coincidentally, video streaming sites are an ideal platform for silent cryptocurrency mining.

Indeed, the ephemeral nature of in-browser miners was often viewed as a weakness, compared to malware miners that remained on your computer, even after a complete reboot. By keeping users on the same page for several minutes, malicious actors increase the chances of solving more calculations, which has a direct impact on their profits.

Malvertising’s ability to affect thousands of victims at once by leveraging the wide reach of ad networks is attractive to online criminals. However, it is not the only means to create such chain reactions. For instance, a third-party plug-in called Browsealoud that helps the blind and visually impaired is relied upon by many sites. The plug-in was maliciously altered to include the Coinhive code, thereby enlisting thousands of unwitting websites and their visitors, including the website of the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) [33], to cryptomine for the benefits of online criminals.

The issue of third-party scripts is not new, and for years security researchers have warned [34] website owners of the dangers of using them. At least, you are advised to apply validation mechanisms [35] before allowing external code to run on your website.

A consistent delivery mechanism, hacked websites have been heavily used to push web miners of various kinds. The problem often stems from a CMS that is not kept up to date by its owner despite numerous remote code execution vulnerabilities regularly being discovered.

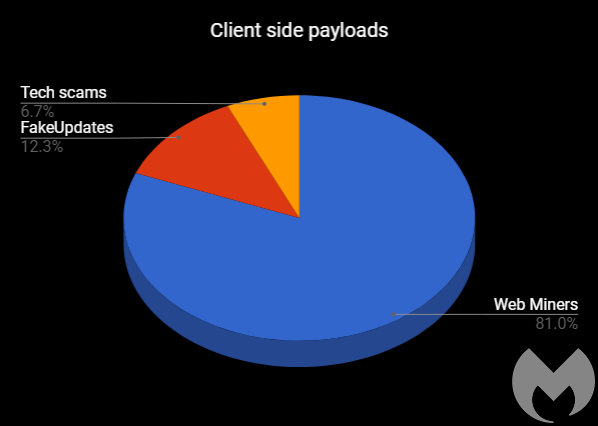

The trend that had started in the fall of 2017 with WordPress and Magento continued in the first few months of 2018 as we witnessed the second and third wave of Drupalgeddon attacks, leveraging CVE-2018-7600 [36] and CVE-2018-7602 [37] in the Drupal CMS. Those vulnerabilities were weaponized almost immediately with in-the-wild attacks, exposing millions of Drupal sites to automated attacks. While criminals loaded server-side malware, often coin miners, we also found [38] that the most common client-side payloads were web miners by a large majority.

Figure 6: Client-side payloads.

Figure 6: Client-side payloads.

You can tell when something is becoming popular because you will find it in the most unusual of places. For example, who would have thought that ad networks themselves would participate in in-browser mining? The result is end-users getting a mix of both online ads and maxed out CPU at the same time [39].

In another case of double-dipping, we noticed that some browser locker templates for tech support scams had been embedded with the Coinhive API with the throttle setting set at 0, meaning the victim’s CPU would be running at full capacity. Perhaps this was meant to get the PC’s fan humming and add additional urgency to the fake BSOD (Figure 7).

And if you were thinking that mobile devices wouldn’t be ideal for CPU intensive mining, think again: others believe that enough of them combined together can produce significant results. Several pages designed specifically for Android, and maybe meant to monetize on bot traffic, collected millions of visits over a period of several months while displaying a CAPTCHA to stop automated mining via Coinhive [40].

In the early days of Coinhive, the mining code was easy to spot in clear text and remote connections were made to static domains, which were trivial to detect and block.

While legitimate site owners would most likely continue to use the unaltered JavaScript API, crooks who had compromised websites predictably started to obfuscate the code, as they had done for years with other types of malicious injections. This made it more difficult for scanners to quickly identify the presence of the Coinhive API within a site, but it also allowed the bad guys to mask to which domain and, more importantly, to which proxy the web miner would connect.

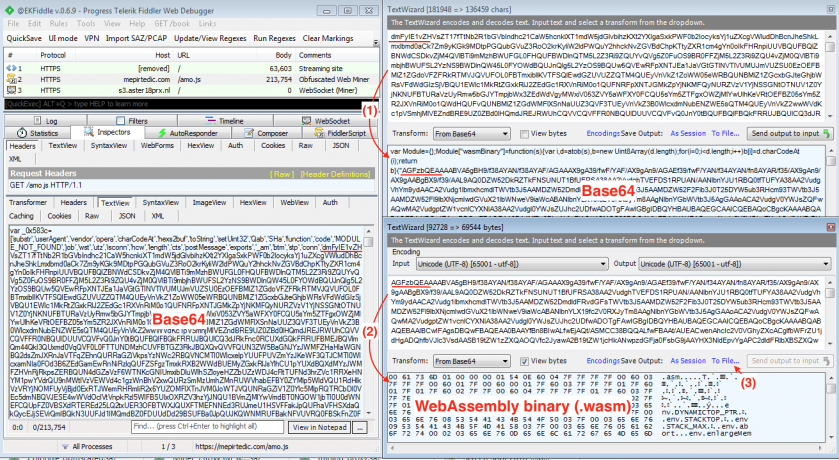

As the main Coinhive domain was already blacklisted by a large number of security products, we noticed a proliferation of new servers for different web miners via a multitude of proxies. In Figure 8, we show an obfuscated JavaScript containing two levels of Base64 encoding that hide an embedded WebAssembly binary [41], which connects to an encrypted WebSocket for asynchronous communication between the browser miner and the backend server.

Figure 8: Obfuscated JavaScript containing two levels of Base64 encoding that hide an embedded WebAssembly binary.

Figure 8: Obfuscated JavaScript containing two levels of Base64 encoding that hide an embedded WebAssembly binary.

In addition, crooks have been leveraging cloud providers to play a cat-and-mouse game with security companies. Not only can those domains or IPs not be blocked entirely without causing massive false positives, they are also cheap to stand up and swap. In one particular campaign [42], a web miner was loaded via now.sh, a legitimate cloud deployment service for applications built using JavaScript (NodeJS) or Docker. Every so often, they would update the hostname to a new one, with some predictability in the hostname, although that is not always the case.

mxcdn1[.]now.sh

mxcdn2[.]now.sh

npcdn1[.]now.sh

sxcdn02[.]now.sh

sxcdn3[.]now.sh

sxcdn4[.]now.sh

sxcdn6[.]now.sh

Figure 9: Hostnames related to web miners.

Shortlinks, a proof-of-work from Coinhive, make users solve a certain number of hashes before they are forwarded to a destination URL. In theory, that idea sounds fair, but unfortunately the number of hashes is completely arbitrary and up to the webmaster to decide. Unsurprisingly, criminals abused it via hidden iframes where the required number of hashes was purposely set very high [43].

One of the weaknesses of a web miner is its lack of persistence, and as a user navigates away from the site or closes the offending tab running the web miner, all cryptomining activity will stop. This is one of the reasons why in-browser mining is popular on video streaming sites, since visitors are more likely to stay put. However, miscreants have found ways to keep the browser mining by using pop-unders tucked in an impossible location, right below the Taskbar’s clock. Despite closing the main browser window, the rogue pop-under tab will remain open and hidden for as long as the computer is running [44].

Another technique mostly used by malware-based miners consists of CPU throttling to avoid attracting any unwanted attention from an overuse of system resources. Web miners also sometimes adopt this technique, but because of their ephemeral nature, crooks will more often do the opposite and abuse all available resources while they can.

On the surface, drive-by mining appears to be fairly benign compared to malware such as banking trojans or ransomware. Indeed, no data is stolen or taken hostage and the performance degradation is usually only temporary.

But for years, the web has been plagued with a general poor user experience, even visiting top trusted sites, where users are often bothered by intrusive and annoying adverts. With in‑browser mining, the user experience can be severely affected when one tab is consuming all available resources.

This is also true for Coinhive’s opt-in version, which, while it requires user consent, can still be abused to run with high CPU usage [45]. Mining at full capacity for long periods of time has a direct relationship with electricity costs, as well as hardware lifespan. Perhaps the impacts are less visible with web miners because they are limited to a browsing session and typically not persistent, unlike their desktop counterparts.

In the longer term, the profits generated from drive-by mining attacks are lining criminals’ pockets and can be used to invest in tools or fund other malicious campaigns. This in itself should be a good enough reason for end users not to be part of these schemes.

For website owners who did not explicitly insert a web miner on their pages, the presence of a web miner usually means that their CMS has been compromised. They are exposing visitors to unwanted code, which will impact their reputation and may even get them blacklisted by popular search engines, hurting their business.

While disabling WebSockets and JavaScript would effectively render in-browser mining impossible, it is not a practical solution for most end-users. Instead, a blacklisting approach was quickly adopted by anti-virus products, ad-blockers, and browser extensions. While in the beginning this approach worked quite well because of the static domains used by Coinhive, it rapidly showed its limitations once threat actors started to use proxies and various levels of obfuscation.

The problem with a database-driven approach is that it is usually reactive in nature, rather than proactive. As far as web miners are concerned, blocklists at the gateway can still provide decent coverage but ideally should be supplemented with other layers of protection on the endpoints.

Blocking ads can help thwart many traffic redirection chains leading to web miners, not to mention many other kinds of payloads. Some browser vendors are starting to offer built-in ad blockers and also cryptomining protection [46]. In general, we can expect to see more heuristic-based solutions in the future that attempt to detect browser abuse, not only from in-browser mining, but also other annoyances such as browser lockers [47], so that users can be in control of their browsing experience.

Unfortunately, the web miners that were active in 2017-18 were a success for all the wrong reasons. We may wonder if that success was due in part to the fact that the business model was ripe for abuse due to a lack of safety precautions. By the time Coinhive announced AuthedMine [48], an API that forces websites to request consent from their visitors using a dialog box, the damage had already been done. In fact, AuthedMine wasn’t just abused with unreasonable levels of throttling, but was also observed running in tandem [49] with the original silent API, bringing much confusion to an already thorny subject.

Each incident further erodes Coinhive’s reputation and increases the scrutiny on in-browser mining, especially considering that the original silent API still exists, thereby inciting forced web miners instead of giving users the choice.

Efforts to unmask [50] the people behind Coinhive provoked some adjustments and what appeared to be an acknowledgement of the need for greater accountability, as well as the need to deal with abuse [51]. However, due to the large number of copycats and possible newcomers, ill-intentioned actors could simply move onto the next available API if Coinhive no longer works out.

In-browser mining in itself is not malicious, but for as long as it is happening without user consent, it will be flagged as malware. In addition to acknowledgement, there is a need for a better understanding of what cryptomining means and why it exists. For the most part, end-users are hearing their PC make loud noises and it is understandable that they may be opposed to it in any way, shape or form.

The drive-by threat landscape is constantly evolving and is a good field indicator of the current state of client-side vulnerabilities. Browser exploit kits have come and gone through the years, but this time around there are questions about their long-term viability as a large-scale infection mechanism.

Perhaps it is just a matter of time before a new cycle begins again, but criminals are not waiting around until that happens. Beside a noted increase in web-based social engineering attacks, the recent reintroduction of in-browser mining fits perfectly into already established distribution channels, such as malvertising and compromised websites.

While drive-by downloads have taken a step back, drive-by cryptomining has emerged as a new phenomenon that went mainstream with Coinhive’s overnight success. Its future depends on various factors, including, of course, the value of cryptocurrencies, which historically has been volatile.

Despite all the negative attention around in-browser mining, legitimate uses still exist, but will require successful endorsements and proper implementations in order to become widely accepted.

[1] Malwarebytes. An Overview of Three Zero-Days. https://www.malwarebytes.com/threezerodays/.

[2] Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation. http://mvd.ru/news/item/1387267/ (in Russian).

[3] Kafeine. Bedep has raised its game vs Bot Zombies. https://malware.dontneedcoffee.com/2016/04/bedepantiVM.html.

[4] Kafeine. Is it the End of Angler? https://malware.dontneedcoffee.com/2016/06/is-it-end-of-angler.html.

[5] Stoyanov, R. The Hunt for Lurk. SecureList. https://securelist.com/the-hunt-for-lurk/75944/.

[6] Gorelik, M. CVE-2018-8174 (VBScript exploit). GitHub. https://github.com/smgorelik/Windows-RCE-exploits/tree/master/Web/VBScript.

[7] Segura, J. RIG exploit kit campaign gets deep into crypto craze. Malwarebytes. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2018/01/rig-exploit-kit-campaign-gets-deep-into-crypto-craze/.

[8] Segura J. Malwarebytes. New Flash Player zero-day comes inside Office document. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/cybercrime/2018/02/new-flash-player-zero-day-comes-inside-office-document/.

[9] Segura, J. Internet Explorer zero-day: browser is once again under attack. Malwarebytes. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2018/05/internet-explorer-zero-day-browser-attack/.

[10] Villeneuve, N.; Homan, J. A New Word Document Exploit Kit. FireEye. https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2015/04/a_new_word_document.html.

[11] Kafeine. ThreadKit += CVE-2018-8174 for 400USD. Twitter. https://twitter.com/kafeine/status/1001112584282607616.

[12] Kafeine. EITest Nabbing Chrome Users with a Chrome Font Social Engineering Scheme. Proofpoint. https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/EITest-Nabbing-Chrome-Users-Chrome-Font-Social-Engineering-Scheme.

[13] Segura, J. ‘FakeUpdates’ campaign leverages multiple website platforms. Malwarebytes. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2018/04/fakeupdates-campaign-leverages-multiple-website-platforms/.

[14] Kafeine. Threat Actor Profile: KovCoreG, The Kovter Saga. Proofpoint. https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/threat-actor-profile-kovcoreg-kovter-saga.

[15] ExecuteMalware. Yahoo! Malvertising! http://executemalware.com/?p=432.

[16] Bitcoin.it. Laszlo Hanyecz. https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Laszlo_Hanyecz.

[17] @bitcoin_pizza. https://twitter.com/bitcoin_pizza?lang=en.

[18] Bitcoin.it. CryptoNight. https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/CryptoNight.

[19] Monero.how. How does Monero’s privacy work? https://www.monero.how/how-does-monero-privacy-work.

[20] WebAssembly. https://webassembly.org/.

[21] asm.js. http://asmjs.org/.

[22] The State of New Jersey. New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs Obtains Settlement with Developer of Bitcoin-Mining Software Found to Have Accessed New Jersey Computers Without Users’ Knowledge or Consent. http://nj.gov/oag/newsreleases15/pr20150526b.html.

[23] Sinegubko, D. Hacked Websites Mine Cryptocurrencies. Sucuri. https://blog.sucuri.net/2017/09/hacked-websites-mine-crypocurrencies.html.

[24] Neumann, R.; Toro, A. In-browser mining: Coinhive and WebAssembly. ForcePoint. https://blogs.forcepoint.com/security-labs/browser-mining-coinhive-and-webassembly.

[25] Mursch, T. Coinhive miner found on official Showtime Network websites in latest case of cryptojacking. Bad Packets Report. https://badpackets.net/coinhive-miner-found-on-official-showtime-network-websites-in-latest-case-of-cryptojacking/.

[26] Liu, C.; Chen, J. Cryptocurrency Web Miner Script Injected into AOL Advertising Platform. Trend Micro. https://blog.trendmicro.com/trendlabs-security-intelligence/cryptocurrency-web-miner-script-injected-into-aol-advertising-platform/.

[27] Google Chrome Help Forum. Malware extension? Extension hacked? https://productforums.google.com/forum/#!topic/chrome/b0JUzg4HYtI.

[28] Abrams, L. Adware Launches In-Browser Mining Sites Pretending to be Cloudflare. BleepingComputer. https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/adware-launches-in-browser-mining-sites-pretending-to-be-cloudflare/.

[29] Oberhaus, D. Is The Pirate Bay’s In-Browser Cryptocurrency Mining Better Than Its Crappy Ads? MotherBoard Vice. https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/ne7nvm/is-the-pirate-bays-in-browser-cryptocurrency-mining-better-than-its-crappy-ads.

[30] Ernesto. How Much Money Can Pirate Bay Make From a Cryptocoin Miner? TorrentFreak. https://torrentfreak.com/how-much-money-can-pirate-bay-make-from-a-cryptocoin-miner-170924/.

[31] Segura, J. Drive-by mining and ads: The Wild Wild West. Malwarebytes. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2017/09/drive-by-mining-and-ads-the-wild-wild-west/.

[32] Liu, C.; Chen, J. Malvertising Campaign Abuses Google’s DoubleClick to Deliver Cryptocurrency Miners. Trend Micro. https://blog.trendmicro.com/trendlabs-security-intelligence/malvertising-campaign-abuses-googles-doubleclick-to-deliver-cryptocurrency-miners/.

[33] BBC. Hackers hijack government websites to mine crypto-cash. http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-43025788.

[34] Sinegubko, D. The Dangers of Hosted Scripts – Hacked jQuery Timers. Sucuri. https://blog.sucuri.net/2014/11/the-dangers-of-hosted-scripts-hacked-jquery-timers.html.

[35] Helme, S. Content Security Policy – An Introduction. https://scotthelme.co.uk/content-security-policy-an-introduction/.

[36] Drupal. Drupal core highly critical remote code execution. https://www.drupal.org/sa-core-2018-002.

[37] Drupal. Drupal core highly critical remote code execution. https://www.drupal.org/sa-core-2018-004.

[38] Segura, J. A look into Drupalgeddon’s client-side attacks. Malwarebytes. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2018/05/look-drupalgeddon-client-side-attacks/.

[39] Zaifeng, Z. Who is Stealing My Power III: An Adnetwork Company Case Study. Netlab360. https://blog.netlab.360.com/who-is-stealing-my-power-iii-an-adnetwork-company-case-study-en/.

[40] Segura, J. Drive-by cryptomining campaign targets millions of Android users. Malwarebytes. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2018/02/drive-by-cryptomining-campaign-attracts-millions-of-android-users/.

[41] VirusTotal. Scan results. https://www.virustotal.com/#/file/cfb676c3ba6a9466ac86ff796ae62bcb0218ad567233b4465a5b948a8ea0a693/detection.

[42] Segura, J. Malicious cryptomining and the blacklist conundrum. Malwarebytes. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2018/03/malicious-cryptomining-and-the-blacklist-conundrum/.

[43] Leal, L. An Old Trick with a New Twist: Cryptomining Through Disguised URL Shorteners. Sucuri. https://blog.sucuri.net/2018/05/cryptomining-through-disguised-url-shorteners.html.

[44] Segura, J. Persistent drive-by cryptomining coming to a browser near you. Malwarebytes. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/cybercrime/2017/11/persistent-drive-by-cryptomining-coming-to-a-browser-near-you/.

[45] Brodkin, J. Salon to ad blockers: Can we use your browser to mine cryptocurrency. ArsTechnica. https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2018/02/salon-to-ad-blockers-can-we-use-your-browser-to-mine-cryptocurrency/.

[46] Kolondra, K. New year, new browser. Opera 50 introduces anti-Bitcoin mining tool. Opera. https://blogs.opera.com/desktop/2018/01/opera-50-introduces-anti-bitcoin-mining-tool/.

[47] Segura, J. Tech support scammers find new way to jam Google Chrome. Malwarebytes. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/malwarebytes-news/2018/02/tech-support-scammers-find-new-way-jam-google-chrome/.

[48] AuthedMine, Coinhive. A Note to Adblock and Antivirus Vendors. https://authedmine.com/.

[49] Segura, J. Compromised site prompting for AuthedMine while running Coinhive’s silent API in the background. https://twitter.com/jeromesegura/status/1000094780834000896.

[50] Krebs, B. Who and What Is Coinhive? KrebsOnSecurity. https://krebsonsecurity.com/2018/03/who-and-what-is-coinhive/.

[51] Coinhive. Report Abuse. https://coinhive.com/info/abuse.