Intezer, Israel

Chinese threat actors have been shown to be predominant in the DDoS ecosystem, there being a high volume of known cross-platform DDoS botnets with alleged Chinese origin operating in Linux as well as Windows systems and exercising long-term activities over the years.

In this paper we will begin with a brief overview of the current most predominant Chinese threat groups, ChinaZ and Nitol, along with some other subgroups.

We will cover their motivations, some of their malware characteristics, and how long they have been operational along with an overview of each group’s background.

Furthermore, we will cover a range of code and artifact similarities between the groups and our give own interpretation of such connections. We will also discuss how Chinese threat groups may seem to be sharing code, showing different cases of code similarities between different families and a case study involving a specific Gh0st RAT variant found in the wild that has been seen in several Chinese threat actor campaigns, including some involving an APT.

Finally, we will summarize our findings and suggest future points of investigation.

In recent years, there has been a significant rise in DDoS attacks, a large proportion of which have been considered to have Chinese origins. Furthermore, China has emerged as having one of the highest rates of DDoS attacks [1]. An example of these attacks is one that targeted GitHub in February 2018 [2] that was linked to a campaign against the anti-censorship project GreatFire [3], forcing the website to go offline for approximately 10 minutes. Another example is the attack against Telegram on 12 June 2019 that was linked with Hong Kong protests [4] against changes in extradition bills.

This series of events shows that a high volume of DDoS operations originate in China. In addition, there is a highly populated and growing community of DDoS threat actors with alleged Chinese origin that have recorded long-term activities.

The Chinese DDoS threat landscape has been found to be complicated in terms of classification, leading to misinterpretations – for example, classifying groups to later find out that specific groups are composed of several subgroups and the other way around, leading the community to use different names to reference, in essence, the same group.

The hierarchy of these groups is not clearly known, nor is it known whether they are part of the same collective. We will be breaking apart some of the most well-known Chinese DDoS groups, revealing bonds that might correlate some of these groups and that might potentially uncover some further leads on how this community operates.

Among the vast number of Chinese DDoS groups, we highlight two groups which will be the main protagonists of this paper: ChinaZ and Nitol.

ChinaZ is an alleged Chinese threat group first reported by MalwareMustDie in November 2014 [5]. This threat group was discovered operating several multi-platform DDoS botnets targeting Linux and Windows systems.

It is important to mention that this group has deployed what may be some of the current most predominant DDoS botnets targeting Linux systems, having developed Linux.Elknot along with its predecessor Linux.BillGates.

This group is known to have been in operation since late 2013 and has the ability to deploy several different DDoS attack methodologies.

In 2014, Avast researchers Peter Kálnai and Jaromír Horejší presented an extensive piece of research on ChinaZ’s cross-platform DDoS tools [6].

Furthermore, in 2016, researchers Ya Liu and Hui Wang from Qihoo 360 presented their findings regarding BillGates [7], in which they explained the several DDoS attacks that the group had conducted, in particular two attacks deployed against 12 root name servers in 2015 [8].

Apart from the Elknot/BillGates DDoS botnets, ChinaZ is known to have developed many others. Figure 1 shows a timeline of some of the malware believed to be linked to ChinaZ.

Figure 1: ChinaZ malware timeline.

We can see that this group started developing DDoS botnets as early as the end of 2013 with the development of Elknot/DNSAmp. 2014 to 2015 was the period in which the greatest volume of malware was developed by this group, implementing seven new DDoS bot strains: BillGates, AESDDoS, IptableX, XorDDoS, MrBlack, DDoSClient and ChinaZ.DDoS. From 2016 to 2018 this group seems not to have been very active, the number of new malware strains dropping considerably. In 2019 a new DDoS bot malware with connections to Elknot was discovered, known as ChaChaBot.

The common victims of this group have been small to medium-sized local businesses, online gaming sites, e-commerce shops and forums.

Monetization has been achieved by deploying DDoS attacks as a service and demanding a ransom to stop the specified attacks.

An interesting fact about the progression of this threat actor group, based on claims made by MalwareMustDie, is that at some point ChinaZ recruited students to develop some of its malware. This was the case with DDoSClient.

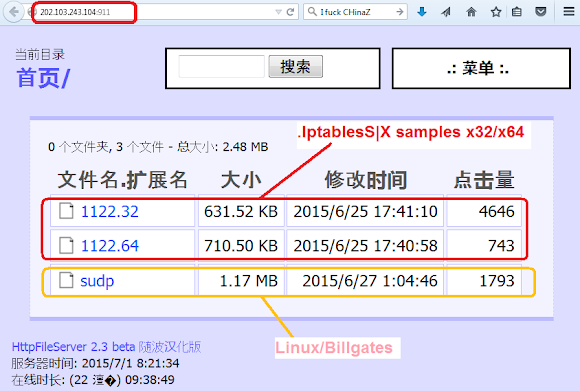

Furthermore, some of these families have been seen being served together in HTTP file servers (also commonly known as HFS), which is the general way these Chinese malware families have been seen hosted. Figures 2–4 show some different ChinaZ malware families being hosted together.

Figure 2: BillGates and Iptables (source: MalwareMustDie).

Figure 3: MrBlack and ChinaZ (source: MalwareMustDie).

Figure 3: MrBlack and ChinaZ (source: MalwareMustDie).

Figure 4: DDoSClient and BillGates (source: Intezer).

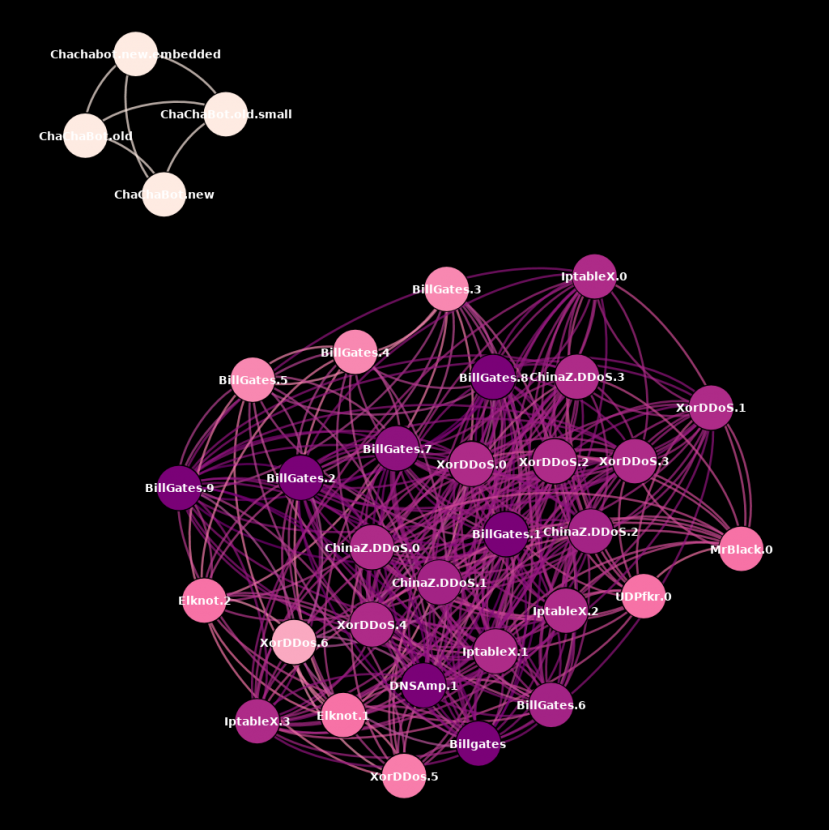

In addition, all these different families share a common code base. We can easily spot this by plotting a graph based on code-reuse connections with an already classified corpus of 34 x86 binaries belonging to the different ChinaZ families against our ELF corpus database composed of hundreds of thousands of classified ELF binaries in which 80% are x86 files. This code reuse analysis is based on genetic analysis – meaning that the code comparison is based on small, already classified fragments of code, excluding common code fragments such as code seen in libraries and other irrelevant pieces of code. The results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: ChinaZ code reuse.

Figure 5: ChinaZ code reuse.

We can differentiate two different clusters, mainly dividing all families discovered from 2014 to 2016 in one cluster and ChaChaBot, which was discovered during 2018, in the other. Each node in the graph represents a different file and edges represent code connections based on genetic analysis. The colour of each node represents the weight of genes for that specific file, and each colour represents the weight of each connection in terms of genes, where darker colours represent a higher weight and lighter colours represent a lower weight of connections.

Furthermore, these two clusters show that the presented Chinese DDoS malware families do share a substantial amount of code.

ChaChaBot allegedly ported code from Elknot, although this common shared code base seems to be significantly different from the original Elknot code, which may imply that it was highly modified. This theory does make sense, especially considering that there is a four-year gap between Elknot and the ChaChaBot family, so it is perfectly feasible that ChaChaBot has integrated some modified Elknot code.

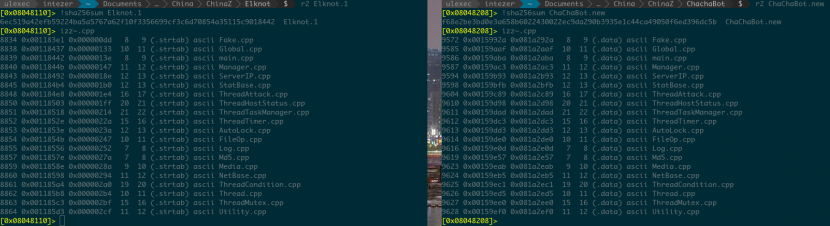

By analysing some of the ChaChaBot binaries, we observed that some of the functions that had been reused from Elknot had the same names as previously seen in Elknot samples, including source code file names (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Some of the functions reused from Elknot in ChaChaBot samples had the same names as previously seen in Elknot samples.

Figure 6: Some of the functions reused from Elknot in ChaChaBot samples had the same names as previously seen in Elknot samples.

We decided to apply a string-reuse analysis on the same test group. The results are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: ChinaZ string reuse.

Figure 7: ChinaZ string reuse.

The graph shown in Figure 7 is a string reuse graph with the same test group. Colour schemes for nodes and edges follow the same convention as previously discussed.

The graph shows that all of the different samples, including ChaChaBot samples, reuse a substantial number of strings, reinforcing the theory that ChaChaBot adapted some Elknot code, despite there being no direct code-reuse connection.

In addition, we have millions of classified strings. In contrast with code reuse, the match is cross‑platform and architecture-agnostic, meaning that we can find strings shared between tools from different operating systems and different architectures.

It has been speculated that this group has been sharing code through Chinese forums, which could have also been a source of monetization and could explain how families with modified code bases, such as ChaChaBot, have emerged.

Nitol is a DDoS botnet that targeted mainly Windows systems that was first discovered around August 2011 [9]. Infections from this botnet were most prevalent in China.

Microsoft researchers in China initially discovered Nitol while investigating the sale of computers loaded with counterfeit copies of the Windows operating system.

It was discovered that most of the Nitol infected endpoints were brand new from the factory, implying that the malware was potentially installed somewhere during the assembly and manufacturing process, and all infected endpoints also had a counterfeit version of the Windows operating system.

On 10 September 2012 [10] Microsoft took legal action against the Nitol botnet, obtaining a court order to sinkhole one of Nitol’s predominant domains for C&C communication, hosted under 3322.org [11].

Nitol’s main outstanding characteristic was that it was developed mainly to spread via removable media and mapped network shares.

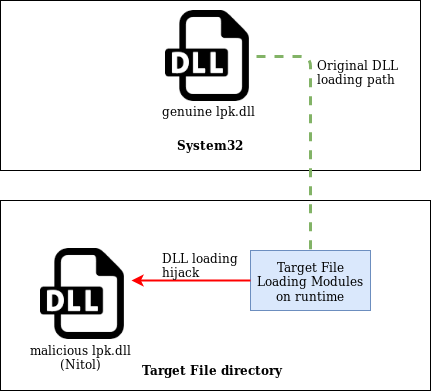

The main Nitol binary comes in the form of a DLL named lpk.dll. The genuine lpk DLL is part of the Microsoft Language Pack and, by default, this DLL is loaded by every process, much like kernel32.dll.

Nitol copies itself in multiple directories and attempts to exploit the module loading process used by Windows. This technique is commonly known as search order hijacking – the malware loads itself into a given process virtual address space, taking precedence over the genuine target library desired to hijack, in this case lpk.dll located at System32. This technique is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Nitol DLL hijacking.

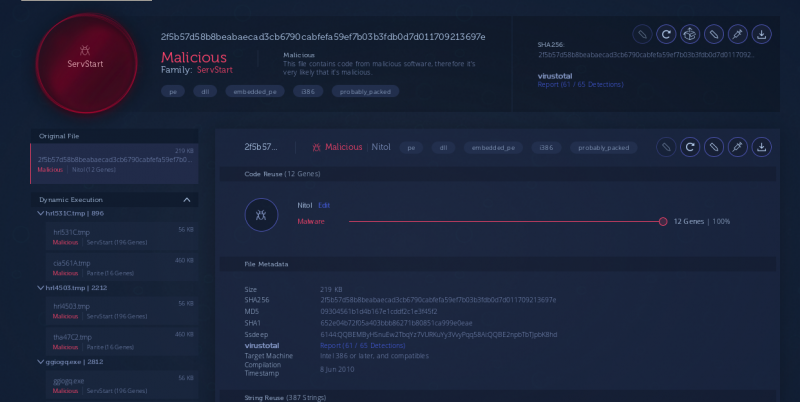

The main lpk.dll Nitol library will drop several other samples with different functionalities.

The most common implant seen dropped by Nitol is a piece of malware known as ServStart.

Figure 9 is a FireEye description [12] of this malware.

SERVSTART (aka Nitol) is a Trojan that installs either as a binary executable or a dynamic link library and registers itself as a service. That service enables a remote user to connect to a remote server, download and run or install other malicious files, stop or restart the system, and perform distributed denial of service activities. The malware is capable of communication via TCP or UDP connections and it installs itself with a mutex to ensure a single copy of the software is installed. It is also capable of updating or uninstalling itself from a system.

Figure 9: FireEye’s description of ServStart.

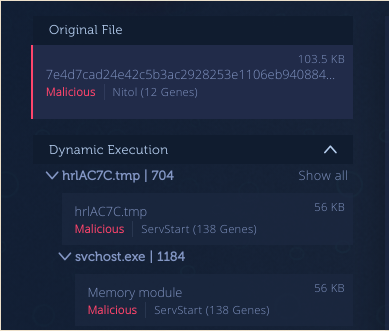

We at Intezer also came across ServStart being dropped by Nitol [13].

Figure 10: ServStart being dropped by Nitol [13].

Nowadays, lpk.dll infection is not commonly seen, although ServStart is a very common piece of malware seen in the wild.

In this section we will go through an investigation we conducted at Intezer while tracking some ChinaZ servers, in which we found connections between ChinaZ and Nitol.

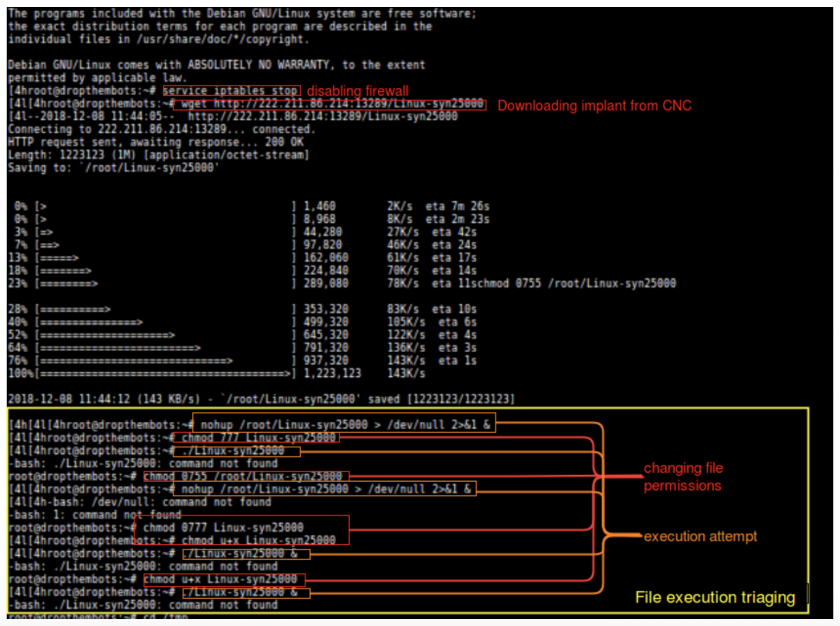

We at Intezer have several deployed honeypots and we monitor different malware behaviour through them. We came across an interesting intrusion conducted via SSH/Telnet credential brute-forcing.

Figure 11 is the log of the intrusion session in one of our honeypots.

Figure 11: Log of the intrusion session in one of our honeypots.

Figure 11: Log of the intrusion session in one of our honeypots.

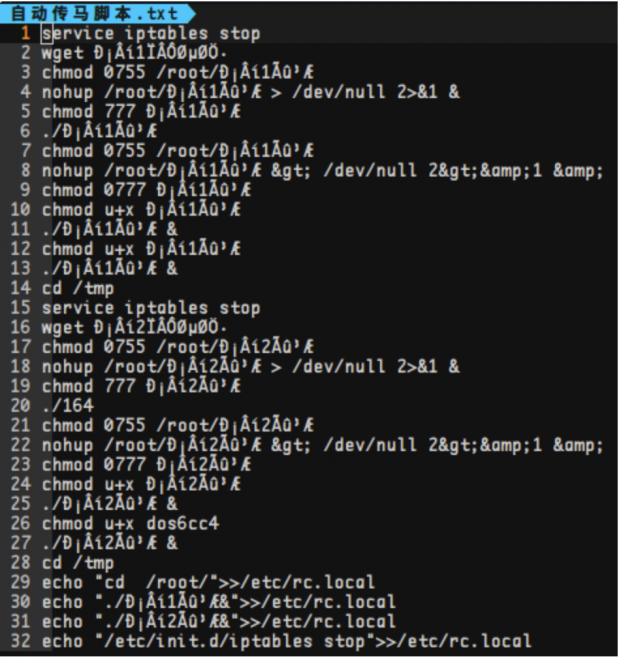

The downloader bash script seems to be fairly simple in logic, changing directories from /root to

/tmp once it detected that the dropped implant could not be executed, after several attempts at changing its file permissions.

Once we accessed where the script was trying to download its corresponding files, we found the files being hosted in a Chinese HTTP File Server (HFS) panel. Figure 12 is a screenshot of this panel.

Figure 12: ChinaZ panel.

Figure 12: ChinaZ panel.

As previously mentioned, ChinaZ is known to use Chinese HFS instances, and unlike other major DDoS botnets such as Mirai, ChinaZ operates mostly on Windows servers.

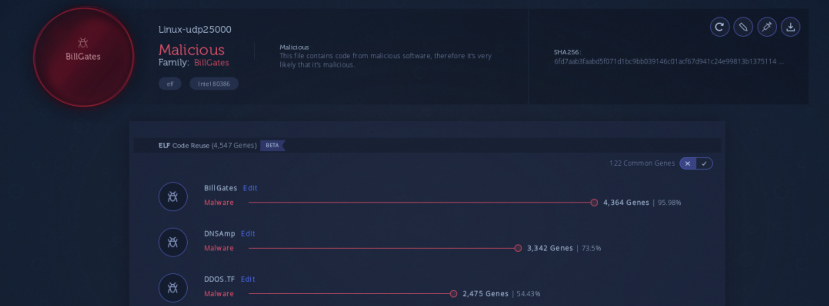

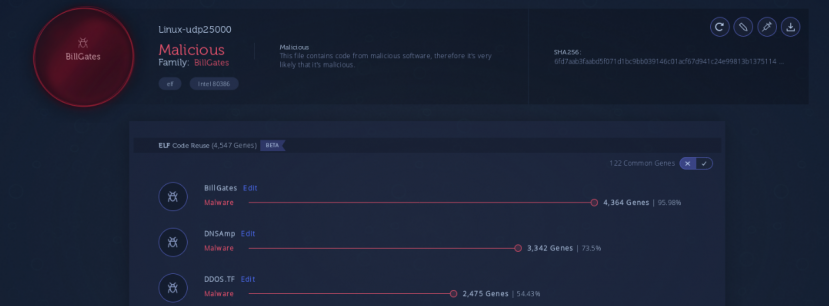

In this particular HFS server we saw various files. The two Linux prefixed files are both regular BillGates builds. We confirmed this based on our code reuse engine, shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13: BillGates analysis [14, 15].

Figure 13: BillGates analysis [14, 15].

Figure 14: ChinaZ vs. Gh0st RAT source comparison.

Figure 14: ChinaZ vs. Gh0st RAT source comparison.

Furthermore, we noticed a hosted Windows binary that we later confirmed to be a Gh0st RAT instance. Figure 14 shows a comparison with the open-source version hosted on GitHub [16].

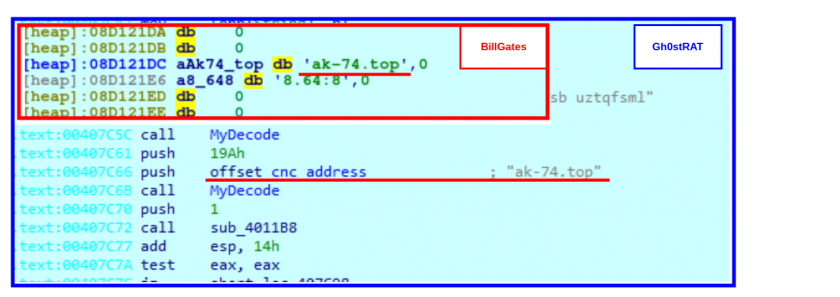

We also wanted to confirm that both the BillGates and the Gh0st RAT instances were operated by the same actor, therefore we checked their C&Cs, which were found to be the same, although they communicated through different channels using different ports, as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15: BillGates and Gh0st RAT instances were operated by the same actor, although they communicated through different channels using different ports.

Figure 15: BillGates and Gh0st RAT instances were operated by the same actor, although they communicated through different channels using different ports.

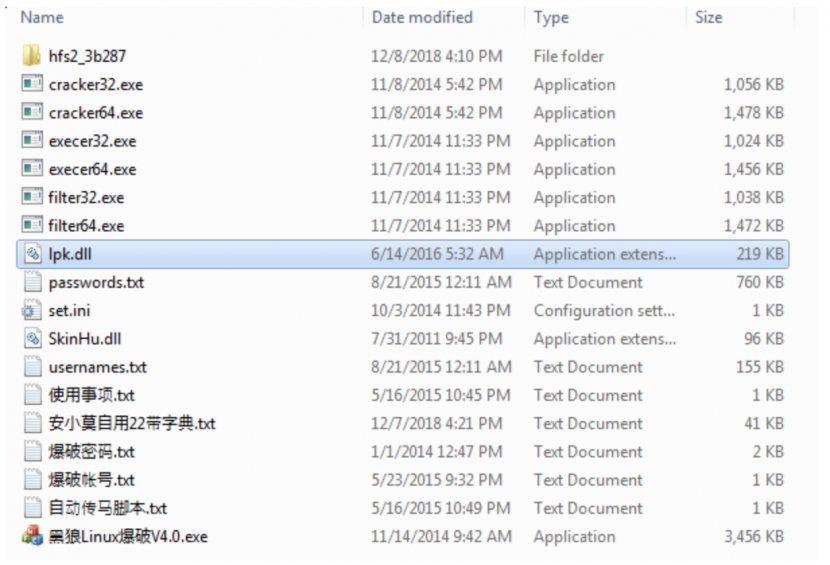

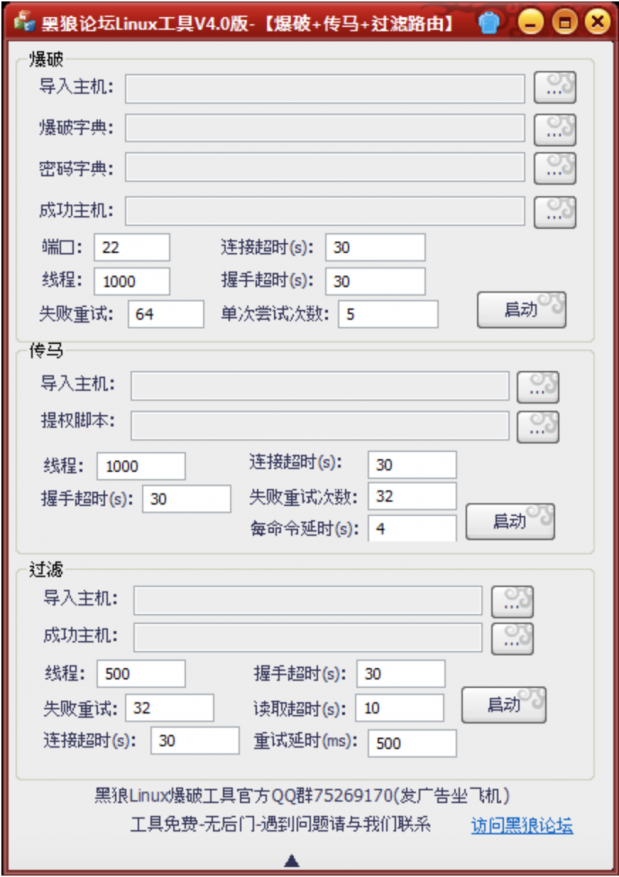

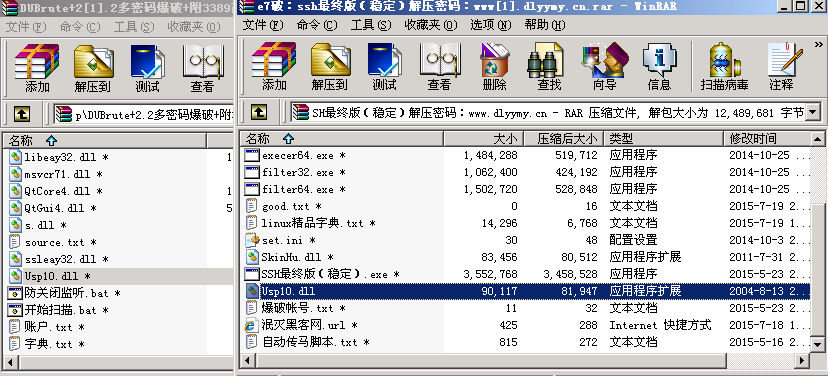

Furthermore, we found a compressed archive labelled ‘Black Wolf Linux Blasting V4.0’ (in Chinese) among the different binaries hosted in the HFS server. Inside this RAR file we encountered the files shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16: Contents of RAR file.

Most interestingly, the contents of the compressed archive appeared to be a Chinese DDoS tool.

Figure 17: DDoS tool.

Figure 17: DDoS tool.

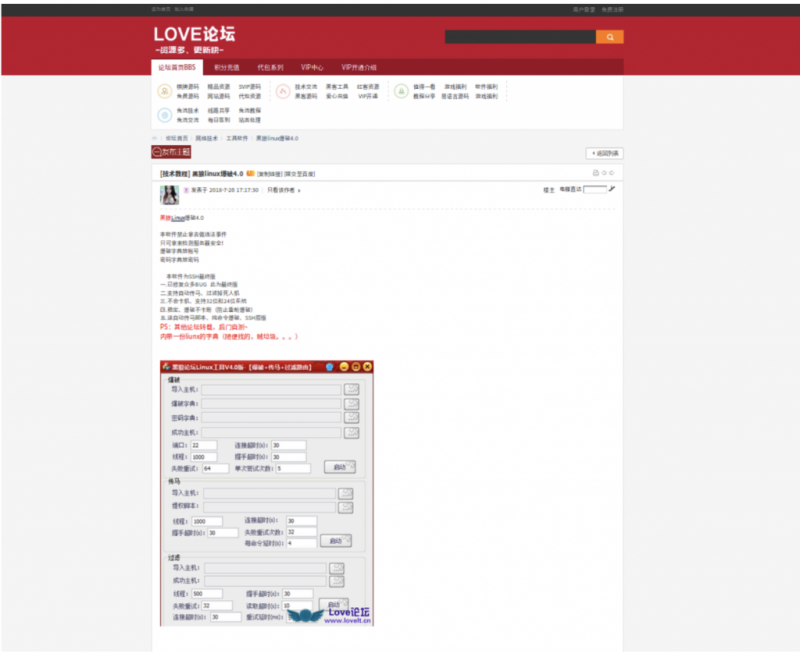

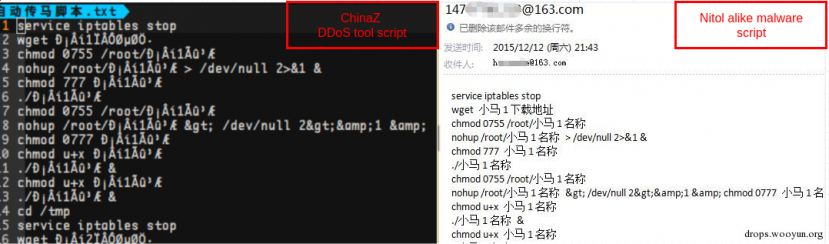

This tool enables users to edit which files will be used on deployment, and other related configurations such as the timeout. We observed this specific DDoS tool advertised in a range of Chinese forums, such as the one shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18: Chinese forum advertising the DDoS tool.

If we analyse one of the scripts inside the zip file and compare it with our initial honeypot hit log, we can assume that the attack was deployed using this tool.

Figure 19: ChinaZ DDoS tool script.

Figure 19: ChinaZ DDoS tool script.

We were not sure whether this Chinese DDoS tool was distributed by ChinaZ, or if the group purchased the tool in order to use it in its campaigns.

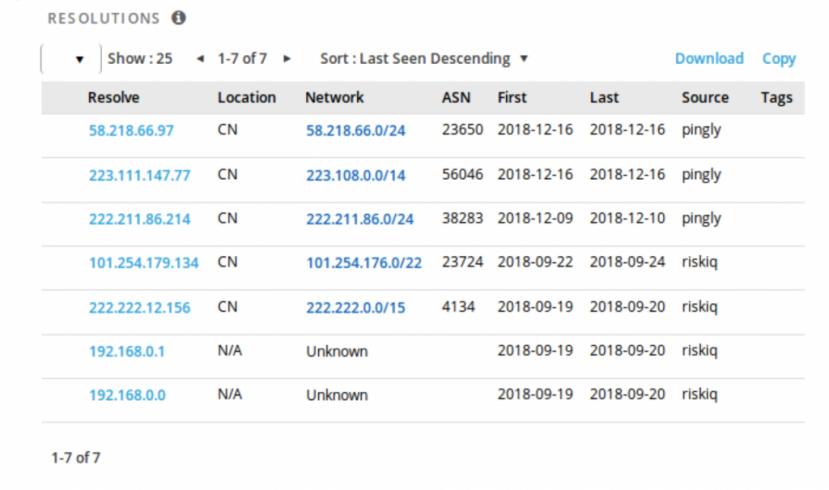

Moreover, after analysing these files, we decided to look up the specific C&C domain name seen in the BillGates and Gh0st RAT instances found in the initial HFS server, to see if this domain had multiple resolutions and find more potential servers linked to this actor. Figure 20 shows the RiskIQ reverse look-up of C&Cs.

Figure 20: RiskIQ C&C reverse lookup.

Figure 20: RiskIQ C&C reverse lookup.

All of the IPs shown in Figure 20 denote a server that would resolve to ‘ak-74.top’, the C&C domain seen in the first HFS server. Based on these resolutions we were able to find other panels such as the one shown in Figure 21.

Figure 21: Second ChinaZ panel.

Figure 21: Second ChinaZ panel.

We instantly recognized the same pattern in terms of the naming convention as well as the types of files being hosted in this HFS server. In contrast with the previous HFS server, this server is only hosting Windows binaries and a compressed archive.

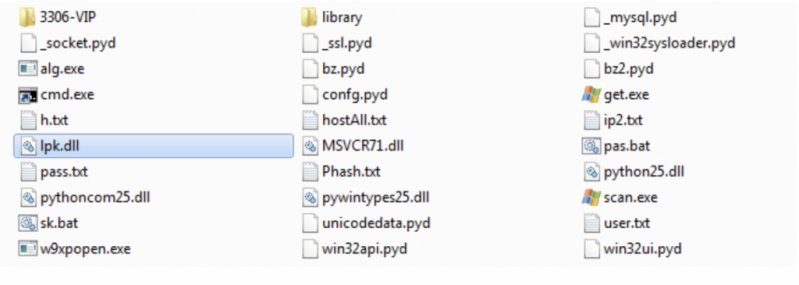

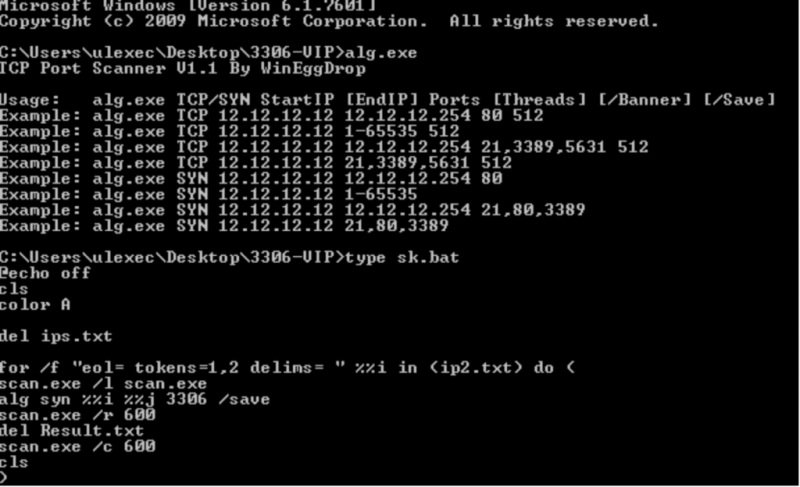

Figure 22 shows a list of the files contained in the 7z compressed file.

Figure 22: Files contained in the compressed file.

Figure 22: Files contained in the compressed file.

These files appear to be composing a port scanner tool written in Python that could also be used to deploy DDoS attacks.

Figure 23: DDoS tool.

In the screenshot shown in Figure 23 we can observe an executable responsible for the main TCP/SYN flood, and the script used to deploy DDoS attacks.

The remaining binaries were another Gh0st RAT and a Windows instance of Linux.DDosClient, also known to have been developed by ChinaZ actors.

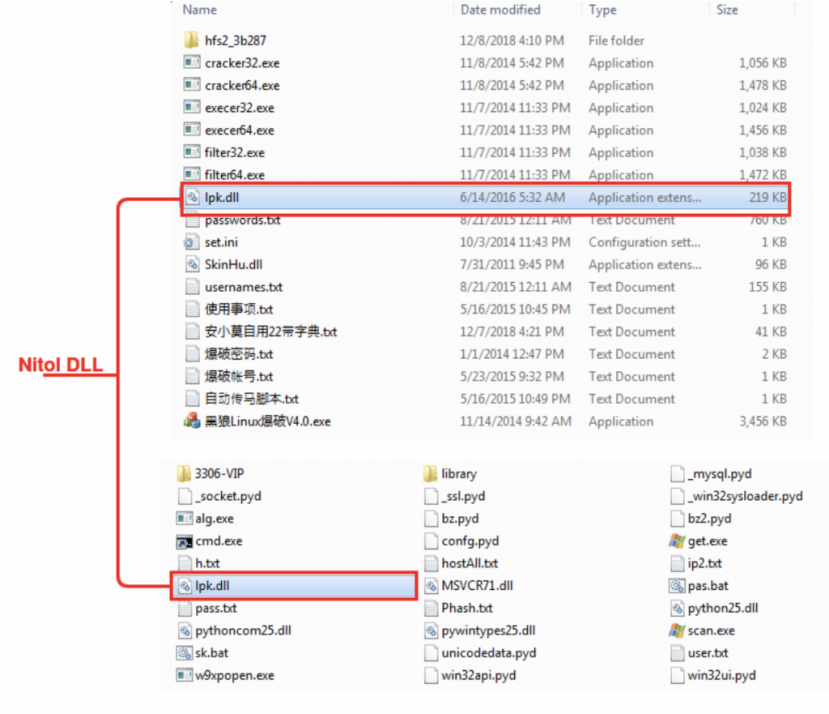

Inside the hosted compressed files were varying components. However, among all of the files, the most notable was a DLL labelled ‘lpk.dll’, which appeared in every hosted compressed archive that we found in this investigation. This DLL has been known to have been hijacked in the past by Nitol [17], as mentioned at the beginning of the paper, and as shown in Figure 24.

Figure 24: Lpk.dll.

Figure 24: Lpk.dll.

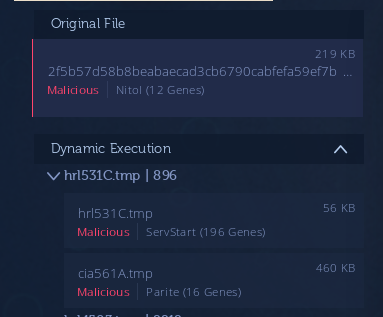

We confirmed, based on code reuse, that this was indeed Nitol, as shown in Figure 25.

Figure 25: Confirmation that the file was Nitol.

Figure 25: Confirmation that the file was Nitol.

After analysing these findings, we came to the conclusion that the actors behind this botnet may be operating on infected physical Windows systems, and consequently deploying malware infected with previous malware belonging to older campaigns, therefore indirectly linking Nitol and ChinaZ.

A fact supporting this theory was that, after analysis, this specific DLL failed to connect to its correspondent C&C, but at some point in the infection chain a Parite file infector was also dropped from both the Nitol DLL implants as well as from the hosted Windows Gh0st RATs (Figure 26).

Figure 26: At some point in the infection chain a Parite file infector was dropped.

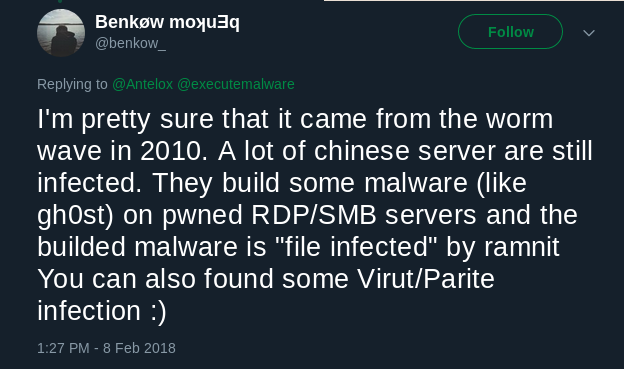

It is known that in 2010 there was a strong infection wave of Chinese servers that, today, are still operative and deploying infected malware. This may be why we can find Parite drops from files hosted in these servers.

Figure 27: Tweet by @benkow_ [19].

It should be noted how little effort is made by the actors to maintain a clean development environment for their newer malware campaigns, if the theory explained above is indeed true.

Based on the previous findings regarding Nitol and ChinaZ, we decided to continue with this investigation in order to figure out whether we could find more artifacts that would link Nitol and ChinaZ.

In this section we will discuss several discovered links between MrBlack from ChinaZ and ServStart from Nitol.

MrBlack [20] is an IoT botnet also known to have Windows variants [21]. As documented by MalwareMustDie, MrBlack is the simplified version of AES.DDoS [22], an ELF DDoS tool of Chinese origin that was in circulation before ChinaZ was ever established.

Throughout our investigation we came across the HFS panel shown in Figure 28.

Figure 28: HFS panel showing DDoSClient and MrBlack.

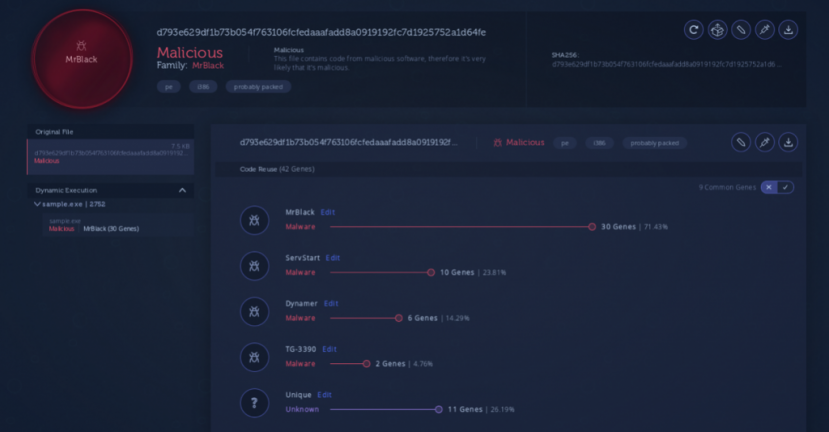

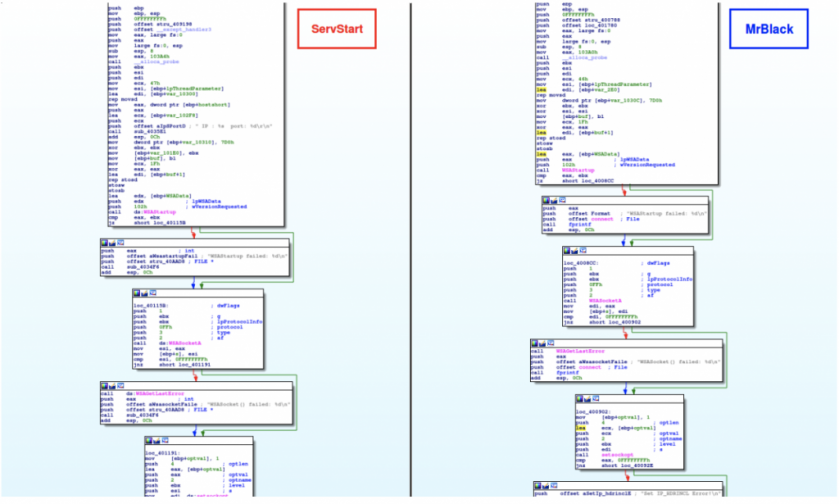

Figure 29 is a code reuse analysis of the hosted Windows binary classifying the file as a Win32/MrBlack instance.

Figure 29: Code reuse analysis [23].

Figure 29: Code reuse analysis [23].

If we look closely we can see that the hosted instance of Win32.MrBlack shares 10 genes with ServStart [25], a trojan associated with the Nitol family, as previously mentioned.

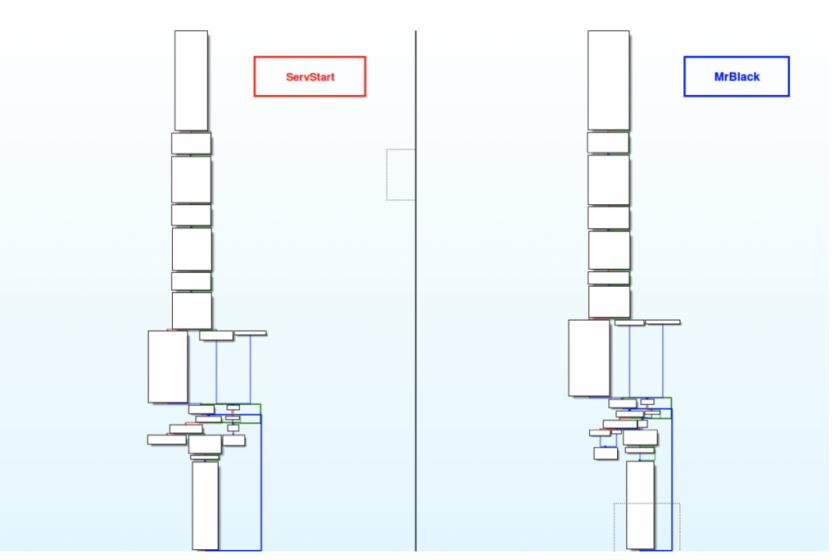

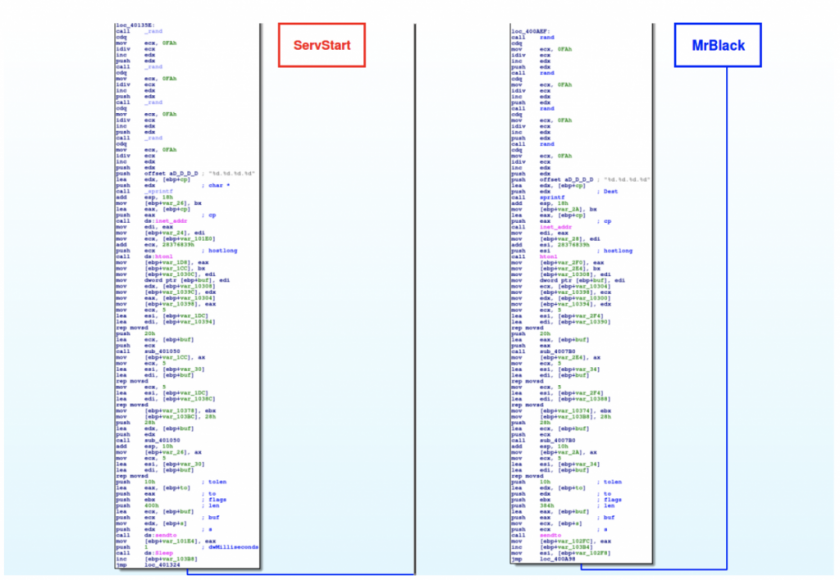

After analysis of these 10 genes we observed that this instance of MrBlack has exactly the same SYN flood function as the ServStart instance (Figure 30).

Figure 30: ServStart vs. MrBlack: the same SYN flood function.

Figure 30: ServStart vs. MrBlack: the same SYN flood function.

We can observe that there are slight variations present throughout the code (Figure 31), but most of the function is identical, specifically the main flood loop (Figure 32).

Figure 31: ServStart vs. MrBlack: slight variations throughout the code.

Figure 31: ServStart vs. MrBlack: slight variations throughout the code.

Figure 32: ServStart vs. MrBlack: most of the function is identical.

Figure 32: ServStart vs. MrBlack: most of the function is identical.

Reinforcing this connection between MrBlack and ServStart, we discovered additional panels such as the one shown in Figure 33.

Figure 33: MrBlack panel.

Figure 33: MrBlack panel.

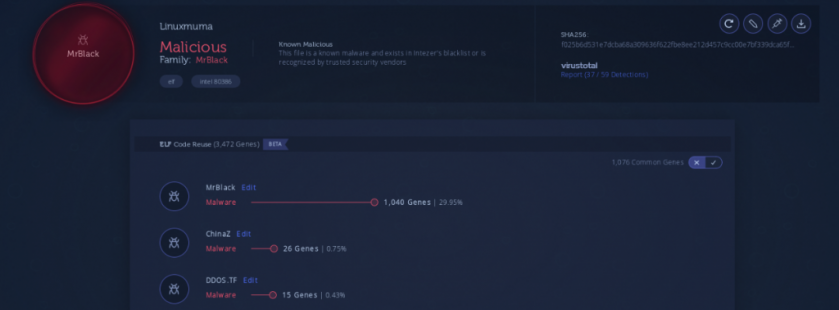

In this panel we found two instances of Linux.MrBlack along with seven instances of a variant of ServStart. We have identified the MrBlack instances based on code reuse (Figure 34).

Figure 34: MrBlack identified based on code reuse [25].

Figure 34: MrBlack identified based on code reuse [25].

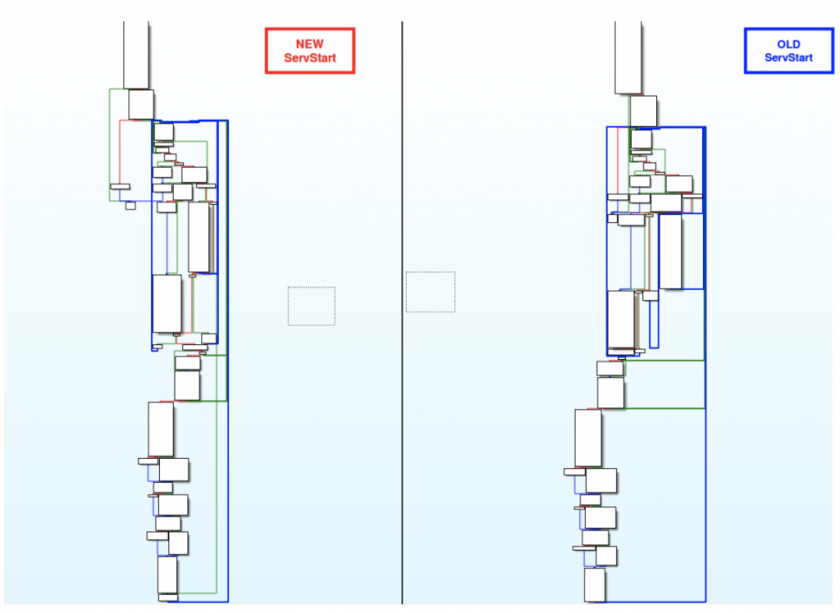

Regarding the ServStart variants, we can see that they share a substantial amount of code with respect to previous ServStart variants (Figure 35).

Figure 35: ServStart variants share a substantial amount of code with previous variants [26].

Figure 35: ServStart variants share a substantial amount of code with previous variants [26].

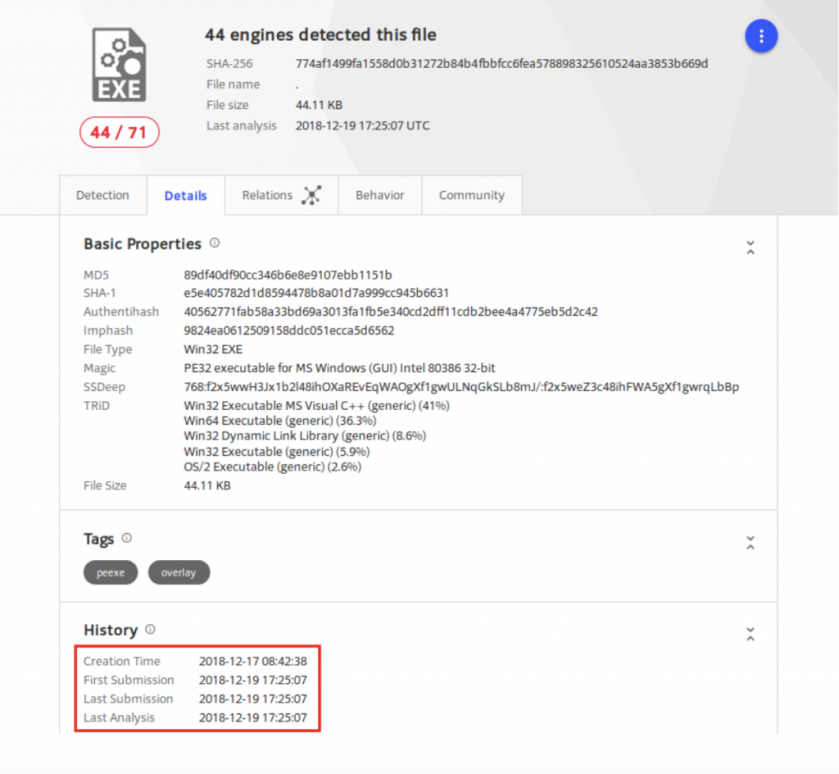

It is important to note that these newer ServStart variants have a recent compilation timestamp, and were only submitted to VirusTotal one week before the day we discovered them.

Figure 36: The newer variants were submitted to VirusTotal a week before we discovered them.

Figure 36: The newer variants were submitted to VirusTotal a week before we discovered them.

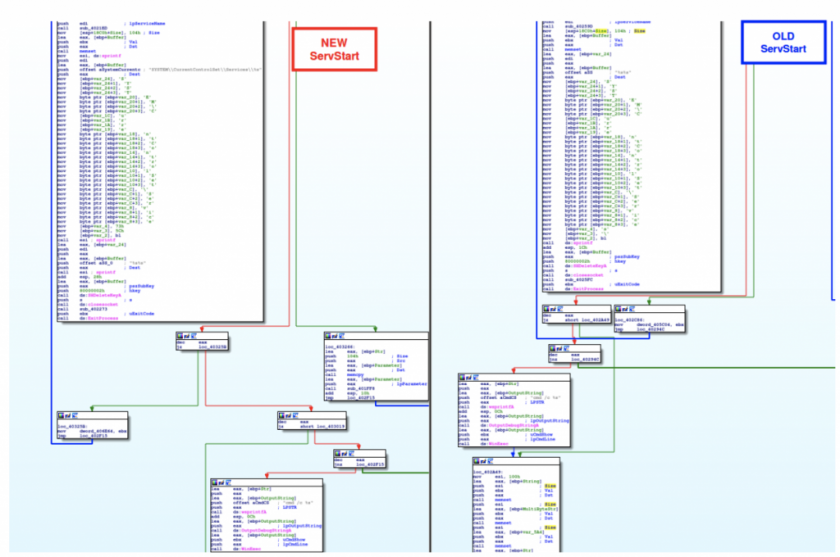

We found several nearly identical functions that had been reused from previous variants of ServStart. Figure 37 is an example of one of these common functions.

Figure 37: Common functions between the new and old ServStarts.

Within the common code we found exact code fragments like the one shown in Figure 38.

Furthermore, we also found common code with noticeable differences between the newer and older ServStart versions. An example of this is shown in Figure 39.

Figure 39: Common code with noticeable differences between the newer and older ServStart versions.

Figure 39: Common code with noticeable differences between the newer and older ServStart versions.

The Gh0st RAT clients we discovered among several HFS servers all appear to be modified instances of Gh0st RAT that share notable characteristics. In this section we will be covering how this Chinese Gh0st RAT variant has been used across a series of known Chinese actors.

These Gh0st RAT variants were initially encountered hosted in ChinaZ HFS servers with the names ‘BX.exe’ or ‘shadow.exe’.

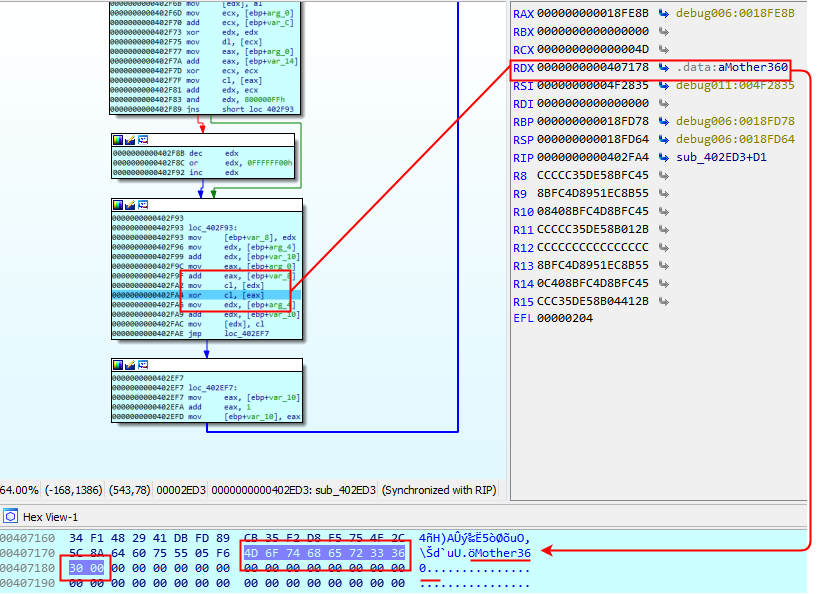

If we take a closer look we observe that there are similarities with the Gh0st RAT instance deployed in Operation PZCHAO by Iron Tiger APT, an APT group with alleged Chinese origin. The RC4 key used to decrypt the C&C is the same as the one used in the PZCHAO campaign, ‘Mother360’.

Figure 40: ChinaZ vs. Iron Tiger.

Based on a Bitdefender blog post about operation PZCHAO, this cryptographic key was not only used to decode the malware’s C&C addresses but was also the key used to decrypt traffic between the client and the C&C server.

Although these two Gh0st RATs may share common code, it is important to understand how to interpret these similarities. As previously mentioned, ChinaZ has been known to employ DDoS botnets in its campaigns. Usually, APT groups do not rely on DDoS attacks. These similarities may not necessarily correlate ChinaZ with Iron Tiger APT, but they may be evidence of the existence of a common Gh0st RAT variant shared within the Chinese community, by having the possibility to have ‘Mother360’ as one of the default hard-coded keys. The reason for this interpretation is based on the fact that APT groups are rarely involved with DDoS operations since the mere thought of correlating these two models does not seem practical, and the probability unlikely.

In addition, we found the use of the same cryptographic key in Gh0st RAT variants used by other Chinese actors.

A report written by Qihoo 360 [28] in 2015 describes a piece of malware very similar to Nitol.

This malware was composed of several artifacts. The artifacts were a Gh0st RAT and a Zip file with a malicious DLL, as shown in Figure 41.

Figure 41: Malicious DLL, Usp10.dll.

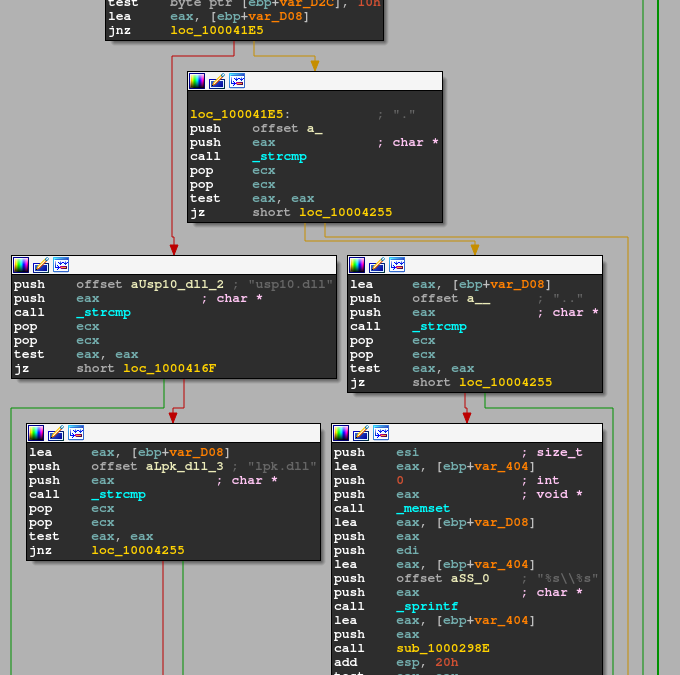

Unlike Nitol’s lpk.dll, this malicious DLL is called Usp10.dll, but once we dive into the DLL we can see that it also has ways to operate as lpk.dll, as shown in Figure 42.

Figure 42: Usp10.dll has ways to operate as lpk.dll.

Figure 42: Usp10.dll has ways to operate as lpk.dll.

Furthermore, the Gh0st RAT instance does decode a subdomain known to be exploited by Nitol in the past within 3322.org domain name, as shown in Figure 43.

Figure 43: The Gh0st RAT decodes a subdomain known to have been exploited by Nitol.

Figure 43: The Gh0st RAT decodes a subdomain known to have been exploited by Nitol.

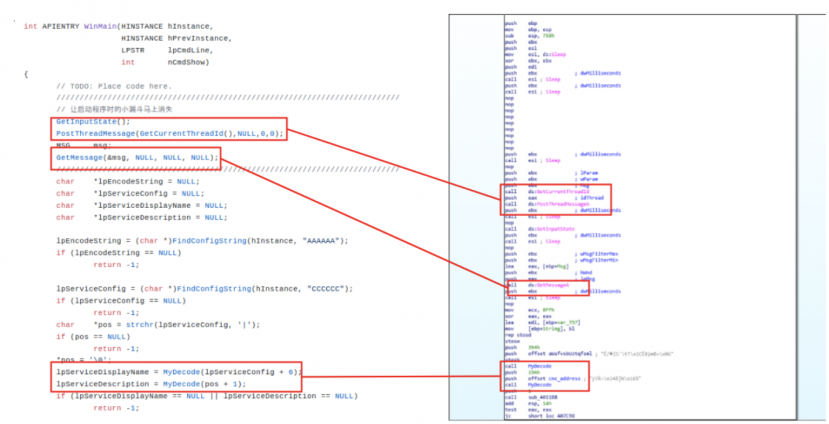

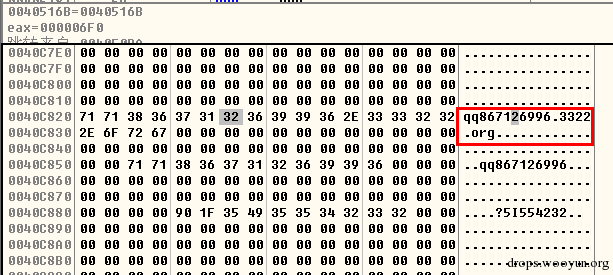

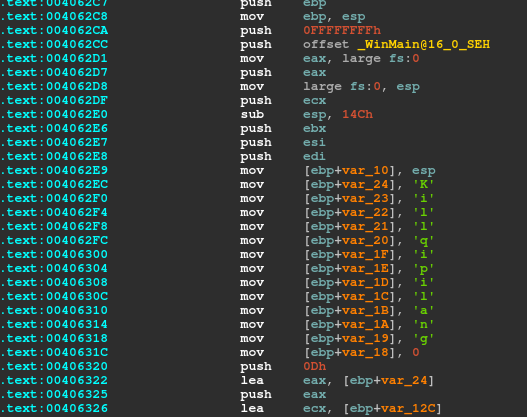

Another interesting feature of this Gh0st RAT is that it has a characteristic stack string at WinMain, as shown in Figure 44.

Figure 44: Nitol has a characteristic stack string at WinMain.

Figure 44: Nitol has a characteristic stack string at WinMain.

Based on this stack string we were able to find different Gh0st RAT instances deployed by the same actor. A majority of these instances use the same cryptographic key as seen in the Gh0st RAT variants used by ChinaZ and Iron Tiger APT: ‘Mother360’ (Figure 45).

Figure 45: ‘Mother360’.

Figure 45: ‘Mother360’.

In addition, this malware resembling Nitol was found to use SMTP as a communication channel, and some of the emails intercepted by Qihoo 360 show identical logs of attacks to those spotted in our honeypot leveraged by ChinaZ, which may imply that these groups are using the same intrusion artifacts in their campaigns (Figure 46).

Figure 46: Some of the emails show identical logs of attacks to those spotted in our honeypot leveraged by ChinaZ.

Figure 46: Some of the emails show identical logs of attacks to those spotted in our honeypot leveraged by ChinaZ.

These findings reinforce the hypothesis that the cryptographic key ‘Mother360’ is not exclusive for any given group but rather a common key in a given Gh0st RAT strain that is shared within the Chinese cybercrime community.

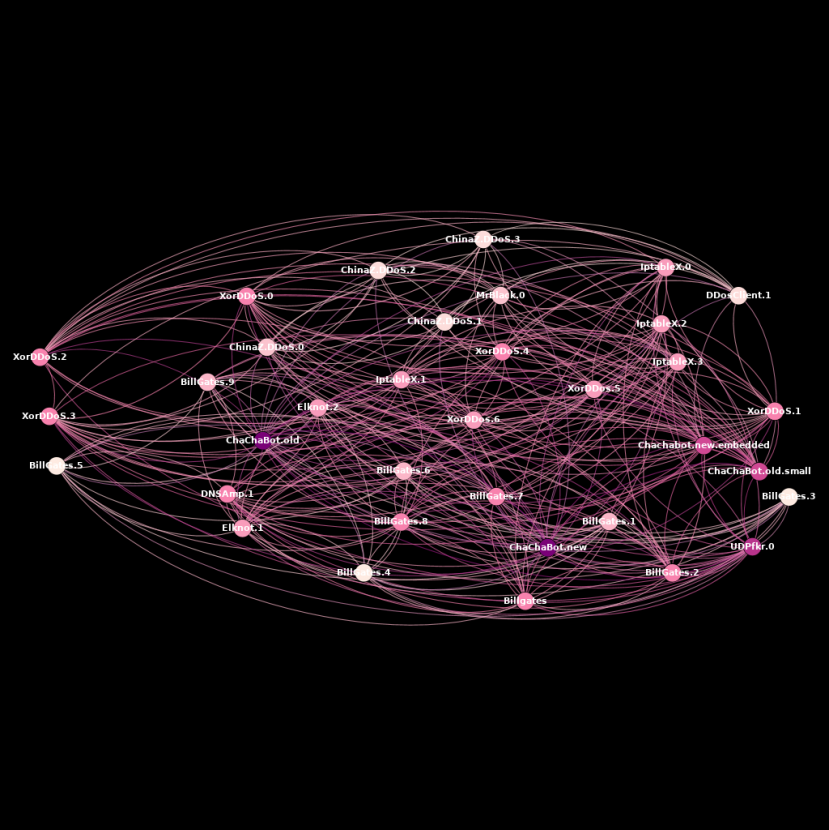

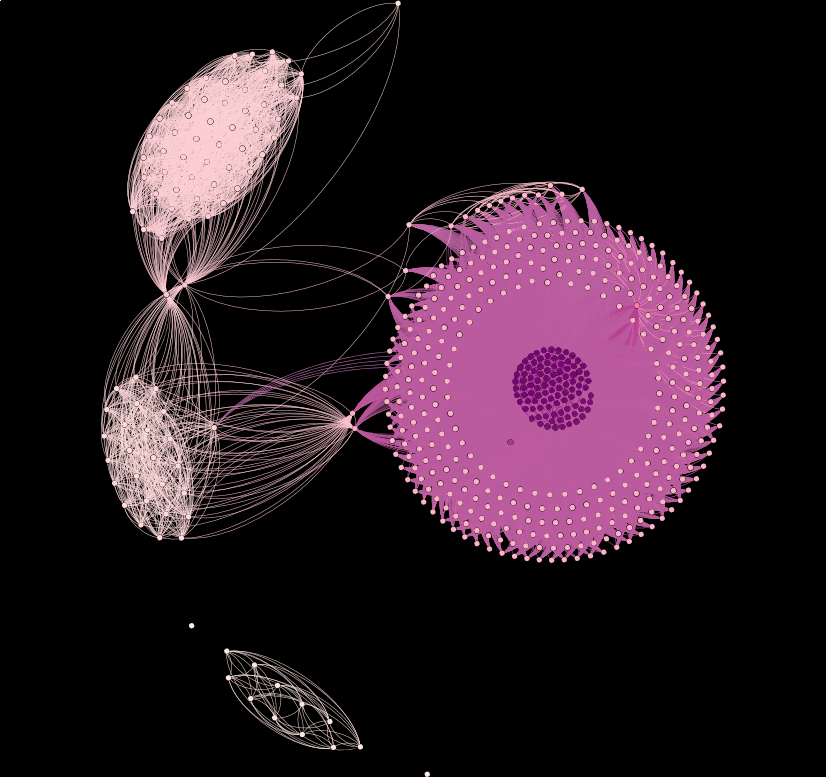

We decided to find Gh0st RAT variants that were using this cryptographic key and plot them on a graph in order to have a better idea of how many potential variants of this Gh0st RAT are using this same cryptographic key. Figure 47 shows the results of plotting 573 Gh0st RAT samples that utilize the same cryptographic key against our code-reuse engine.

Figure 47: The results of plotting 573 Gh0st RAT samples that utilize the ‘Mother360’ cryptographic key against our code-reuse engine.

Figure 47: The results of plotting 573 Gh0st RAT samples that utilize the ‘Mother360’ cryptographic key against our code-reuse engine.

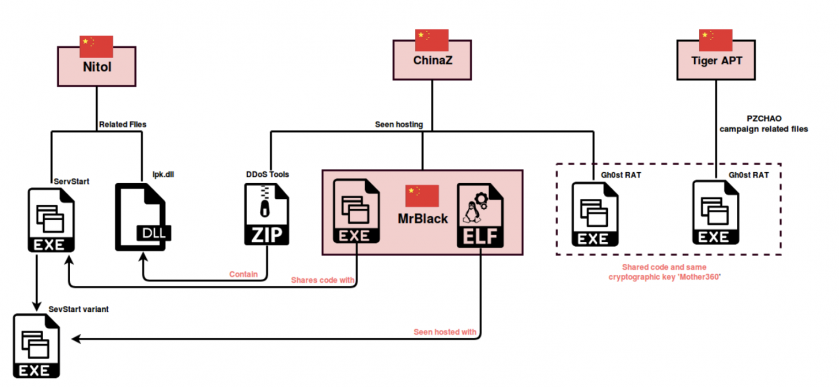

In this paper we have covered several artifacts. A summary of the findings regarding Nitol and ChinaZ are the following:

These two groups have been shown to share the same goals in their campaigns with an emphasis on the deployment of DDoS botnets. In addition, both groups have alleged Chinese origins.

A range of ChinaZ’s Windows servers have been infected by Nitol artifacts. These two families share relevant code with one another, such as DDoS flood implementations, and new ServStart variants have been spotted being hosted alongside MrBlack Linux instances.

Regarding the several Gh0st RAT variants found using the cryptographic key ‘Mother360’ we confirmed that this key is not exclusive to any specific group, although all of the Gh0st variants found using this cryptographic key have been seen used by some Chinese threat actor.

These findings suggest that a common practice of Chinese threat actors is to collaborate in communities. We based this conclusion on the high ratio of code similarities in malware belonging to different groups, the integration of similar pieces of malware with specific characteristics such as the Gh0st RAT case study (and potentially ServStart), and the use of similar modus operandi to deploy and host their malware.

An overview of the findings is shown in Figure 48.

Figure 48: Overview of our findings.

Figure 48: Overview of our findings.

[1] Kupreev, O.; Badovskaya, E.; Gutnikov, A. DDoS Attacks in Q3 2018. Securelist. October 2018. https://securelist.com/ddos-report-in-q3-2018/88617/.

[2] Russel, J. The world’s largest DDoS attack took GitHub offline for less than ten minutes. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2018/03/02/the-worlds-largest-ddos-attack-took-github-offline-for-less-than-tens-minutes/.

[3] Fisher, D. DDoS Attack on GitHub Linked to Earlier One Against GreatFire.org. Threatpost. March 2015. https://threatpost.com/ddos-attack-on-github-linked-to-earlier-one-against-greatfire-org/111919/.

[4] Griffiths, J.; Regan, H.; Ben Westcott, B.; George, S.; Hollingsworth, J. CNNHong Kong protests over China extradition bill. CNN. June 2019. https://edition.cnn.com/asia/live-news/hong-kong-protests-june-12-intl-hnk/index.html.

[5] MMD-0030-2015 - New ELF malware on Shellshock: the ChinaZ. Malware Must Die! January 2015. http://blog.malwaremustdie.org/2015/01/mmd-0030-2015-new-elf-malware-on.html.

[6] Kálnai, P.; Horejší, J. Chinese Chicken: Multiplatform DDoS botnets. Botconf. https://www.botconf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/2014-2.10-Chinese-Chicken-Multiplatform-DDoS-Botnets.pdf.

[7] Liu, Y.; Wang, H. The Elknot DDoS Botnets We Watched. Virus Bulletin. https://www.virusbulletin.com/uploads/pdf/conference_slides/2016/Liu_Wang-vb-2016-TheElknotDDoSBotnetsWeWatched.pdf.

[8] Events of 2015-11-30. https://root-servers.org/news/events-of-20151130.txt.

[9] https://web.archive.org/web/20130113130129/http:/blogs.technet.com/cfs-filesystemfile.ashx/__key/communityserver-blogs-components-weblogfiles/00-00-00-80-54/3755.Microsoft-Study-into-b70.pdf.

[10] Leydon, J. Microsoft seizes Chinese dot-org to kill Nitol bot army. The Register. September 2012. https://www.theregister.co.uk/2012/09/13/botnet_takedown/.

[11] Leydon, J. Chinese Nitol botnet host back up after Microsoft settles lawsuit. The Register. October 2012. https://www.theregister.co.uk/2012/10/04/nitol_botnet_settlement/.

[12] Cyber threats to the aerospace and defense industries. FireEye. https://www.fireeye.com/content/dam/fireeye-www/current-threats/pdfs/ib-aerospace.pdf.

[13] ServStart. Intezer Analyze. https://analyze.intezer.com/#/analyses/76e7c95a-f5ea-4c86-bd7d-0b1a982962c6.

[14] BillGates. Intezer Analyze. https://analyze.intezer.com/#/files/2c7fa76ff852ba960e2eed6a135f4e614366005819d78a87401d875faeff2d40.

[15] BillGates. Intezer Analyze. https://analyze.intezer.com/#/files/6fd7aab3faabd5f071d1bc9bb039146c01acf67d941c24e99813b1375114e908.

[16] gh0st. https://github.com/sincoder/gh0st.

[17] Analysis of Nitol. Hard Work Never Fails. July 2017. http://www.edison-newworld.com/2017/07/analysis-of-nitol.html.

[18] ServStart. Intezer Analyze. https://analyze.intezer.com/#/files/2f5b57d58b8beabaecad3cb6790cabfefa59ef7b03b3fdb0d7d011709213697e.

[19] @benkow_. https://twitter.com/benkow_/status/961713159630393346?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E961713159630393346&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.intezer.com%2Fblog-chinaz-relations%2F.

[20] Zeifman, I.; Atias, R.; Gayer, O. Lax Security Opens the Door for Mass-Scale Abuse of SOHO Routers. Imperva. May 2015. https://www.incapsula.com/blog/ddos-botnet-soho-router.html.

[21] MMD-0048-2016 - DDOS.TF = (new) ELF & Win32 DDoS service with ASP + PHP/MySQL MOF webshells. Malware Must Die! January 2016. http://blog.malwaremustdie.org/2016/01/mmd-0048-2016-ddostf-new-elf-windows.html.

[22] MMD-0026-2014 - Linux/AES.DDoS: Router Malware Warning | Reversing an ARM arch ELF. Malware Must Die! September 2014. http://blog.malwaremustdie.org/2014/09/reversing-arm-architecture-elf-elknot.html.

[23] ChinaZ.DDoS. Intezer Analyze. https://analyze.intezer.com/#/files/7495be154047e2c3c3b9735d61c6f1256eea776eb536e42f2ea76d5c11fc7f84.

[24] Win32/Nitol. Microsoft Security Intelligence. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/wdsi/threats/malware-encyclopedia-description?Name=Win32%2FNitol.

[25] MrBlack. Intezer Analyze. https://analyze.intezer.com/#/files/f025b6d531e7dcba68a309636f622fbe8ee212d457c9cc00e7bf339dca65fec2.

[26] ServStart. Intezer Analyze. https://analyze.intezer.com/#/files/774af1499fa1558d0b31272b84b4fbbfcc6fea578898325610524aa3853b669d.

[27] Operation PZCHAO Inside a highly specialized espionage infrastructure. Bitdefender. https://download.bitdefender.com/resources/files/News/CaseStudies/study/185/Bitdefender-Business-2017-WhitePaper-PZCHAO-crea2452-en-EN-GenericUse.pdf.

[28] Qihoo 360 report (translation). https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=zh-CN&u=https://wooyun.js.org/drops/%25E7%25BD%2591%25E7%25BB%259C%25E5%25B0%258F%25E9%25BB%2591%25E6%258F%25AD%25E7%25A7%2598%25E7%25B3%25BB%25E5%2588%2597%25E4%25B9%258B%25E9%25BB%2591%25E8%2589%25B2SEO%25E5%2588%259D%25E6%258E%25A2.html&prev=search.

ChinaZ Gh0st RAT variant with ‘Mother360’ key:

A9c54bdba780bcdc34f15b62f0ac1da8bcf4d65b4587d0d95bd2a9b5be5dfee6

908d817f81f9276f5afad1a33a7e2de7566fd5c967ad95782a4d904ca0e5efdd

9e24ba7304ae7c4f153fa8e97d2e6779d0e4377cee270b83d20d91afef7fe6f4

Iron Tiger APT gh0st RAT:

D4262bbfe779d18b83b950bb993d3d46154bf1da5a4868ff6fa3e54c167eed71

BillGates:

92c191c41bcc701de5d633a0edb8cab6085ea13ede079651a2cc4a4ae54b29bb

6fd7aab3faabd5f071d1bc9bb039146c01acf67d941c24e99813b1375114e908

Infected ChinaZ DDoS tools with Nitol:

B883b32264bcafd0c5ede5ff7399388feb51dbdf183f7ad52024c08cd221d574

23c69edc4695f6c2184484682757f024f0e20573dba599030fde1cdaeae9915c

ChinaZ.DDoSClient:

80952e211eb98773909f0f3e7ce783ce2f410327058a4760efad2ff0dbebcb88

D97ffba4169df8b206f6fc588ba594e84539b321fae9247723d6b42940116fa5

A8d0928098cc43e7b9e8ba3b03507d342489dea832816dfc083c356b346f8a3d

7495be154047e2c3c3b9735d61c6f1256eea776eb536e42f2ea76d5c11fc7f84

Win32/MrBlack:

D793e629df1b73b054f763106fcfedaaafadd8a0919192fc7d1925752a1d64fe

Linux/MrBlack:

F025b6d531e7dcba68a309636f622fbe8ee212d457c9cc00e7bf339dca65fec2

Fb69075f4383f3537af46d2098b3bcdcb7c1bdd6896c580cd9ead6f56fb5219c

ServStart:

4f4f24f0333ed6e8883971129f216fab608b6e4d0c97c58a2b3b6a1106c77bf7

7db53e95a1339d4d023d61087907a5b07bf6720a2dd88b12882a2c5c201a92ea

7e6a2448e06a1d97ff317a5dc4ed969cef077a3568fd214cbe61854b7ff1a6d1

New ServStart:

774af1499fa1558d0b31272b84b4fbbfcc6fea578898325610524aa3853b669d

E3b0c44298fc1c149afbf4c8996fb92427ae41e4649b934ca495991b7852b855

D104daec5e990de0233efdde8747a1d829c90b7b9a2169a7bcf5744fa1d95e6e