Carbon Black, Japan

Compiler-level obfuscations, like opaque predicates and control flow flattening, are starting to be observed in the wild and are likely to become a challenge for malware analysts and researchers. Opaque predicates and control flow flattening are obfuscation methods that are used to limit malware analysis by defining unused logic, performing needless calculations, and altering code flow so that it is not linear. Manual analysis of malware utilizing these obfuscations is painful and time-consuming.

ANEL (also known as UpperCut) is a RAT used by APT10, typically targeting Japan. All recent ANEL samples are obfuscated with opaque predicates and control flow flattening. In this paper I will explain how to de-obfuscate the ANEL code automatically by modifying the existing IDA Pro plug-in HexRaysDeob.

The modified tool is available publicly and this implementation has been found to deobfuscate approximately 92% of encountered functions in the tested samples. Additionally, most of the failed functions can be properly deobfuscated in IDA Pro 7.3. This provides researchers with an approach with which to attack such obfuscations, which could be adopted by other families and other threat groups.

The Carbon Black Threat Analysis Unit (TAU) analysed a series of malware samples that utilized compiler-level obfuscations. For example, opaque predicates were applied to Turla Mosquito [1] and APT10 ANEL samples. Another obfuscation, control flow flattening, was applied to APT10 ANEL samples and the Dharma ransomware packer.

ANEL is a RAT program used by APT10 and is observed solely in Japan. According to Secureworks [2], all ANEL samples whose version is 5.3.0 or later are obfuscated with opaque predicates and control flow flattening.

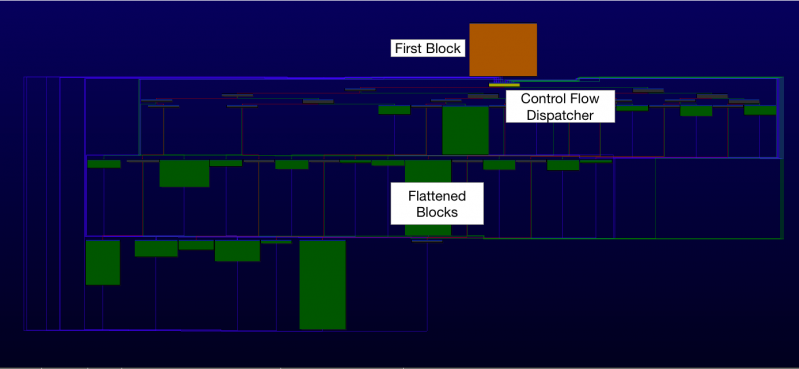

‘Opaque predicate’ is a programming term that refers to decision making where there is actually only one path. For example, this can be seen as calculating a value that will always return True. ‘Control flow flattening’ is an obfuscation method where programs do not flow cleanly from beginning to end. Instead, a switch statement is called in a loop with multiple code blocks, each of which performs operations, as detailed later in this paper (see Figure 10).

The obfuscations used by ANEL looked similar to the ones described in the Hex-Rays blog [3], but the IDA Pro plug-in HexRaysDeob [4] didn’t work for one of the obfuscated ANEL samples because the tool had been made for another variant of the obfuscation.

TAU investigated the ANEL obfuscation algorithms then modified the HexRaysDeob code to defeat the obfuscations. After the modification, TAU was able to recover the original code.

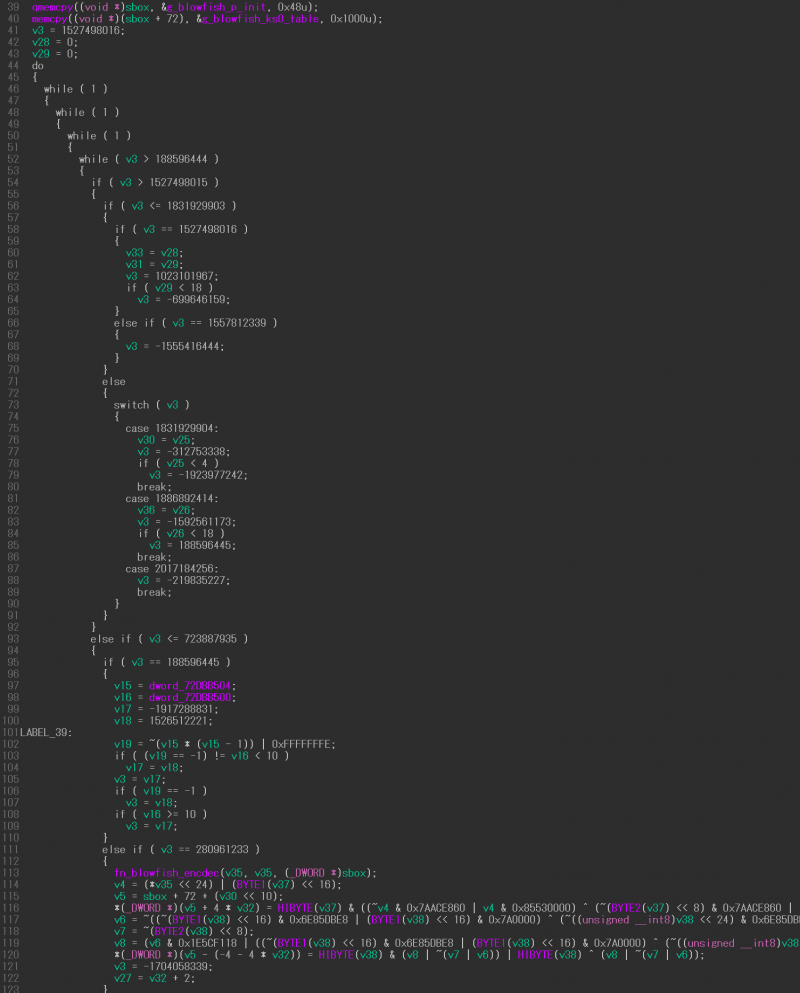

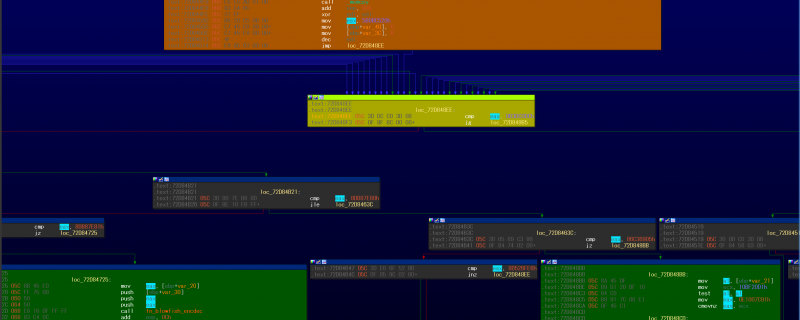

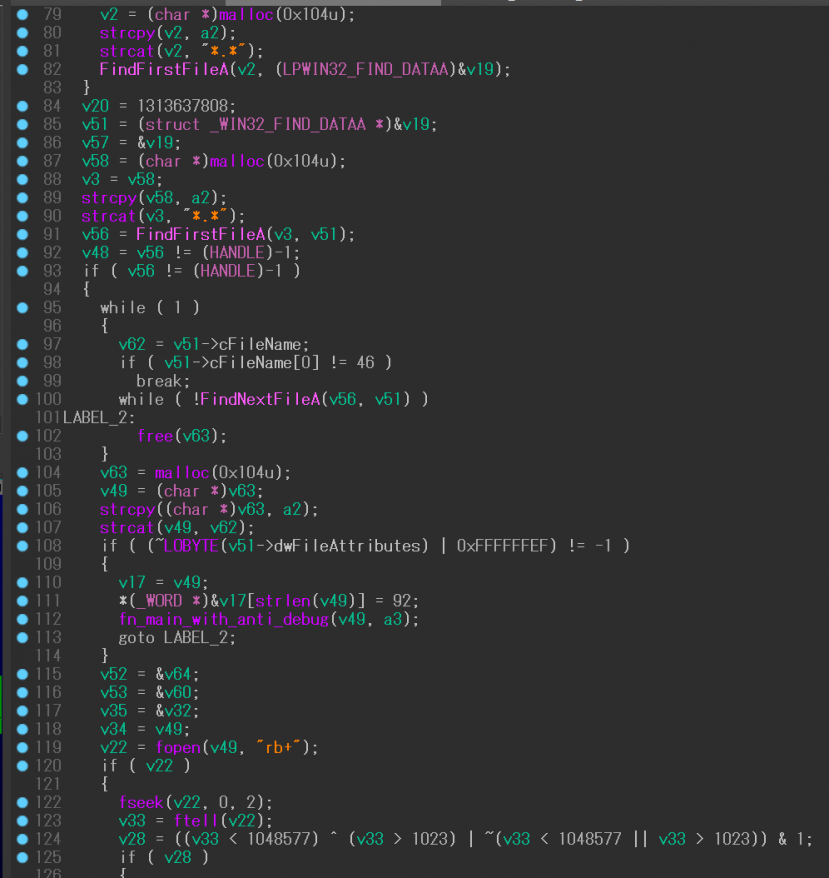

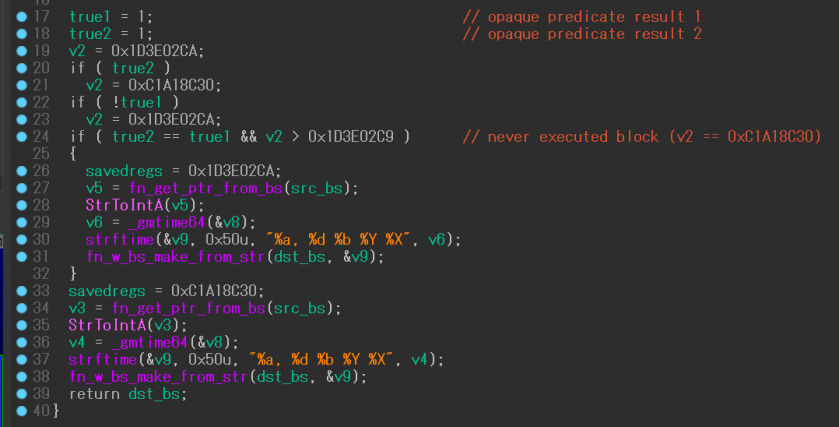

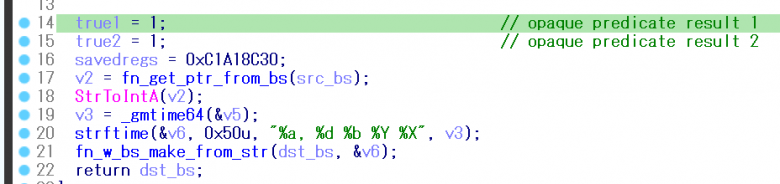

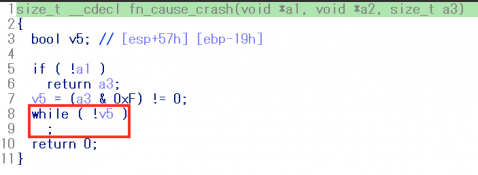

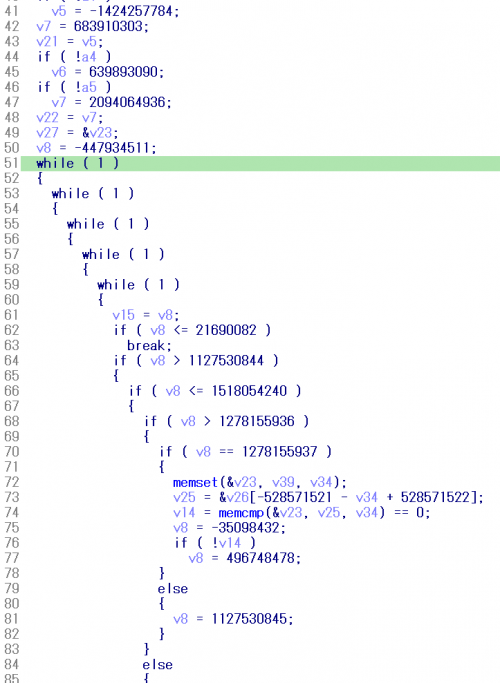

Figure 1 shows an example of an obfuscated function; Figure 2 shows the same function once it has been deobfuscated.

Figure 1: Obfuscated function example (all codes cannot be displayed in a screen).

Figure 1: Obfuscated function example (all codes cannot be displayed in a screen).

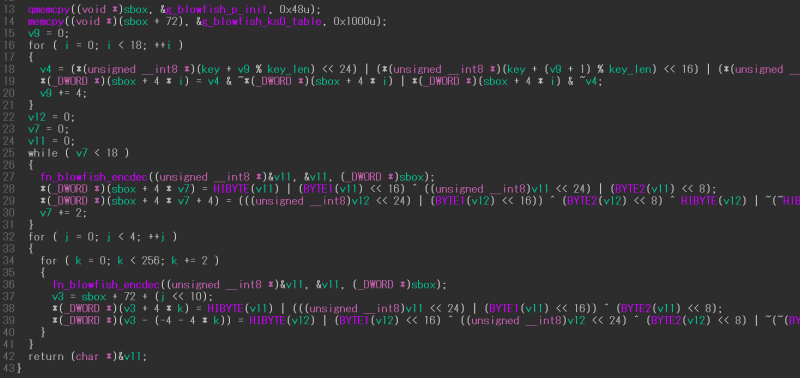

Figure 2: Deobfuscated result of the function shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2: Deobfuscated result of the function shown in Figure 1.

HexRaysDeob is an IDA Pro plug-in written by Rolf Rolles to address obfuscation seen in binaries. In order to perform the deobfuscation, the plug-in manipulates the IDA intermediate language called microcode. If you aren’t familiar with those structures (e.g. microcode data structures, maturity level, Microcode Explorer and so on), you should read his blog post [3]. Rolles also provides an overview of each obfuscation technique in the same post.

HexRaysDeob installs two callbacks when loading:

Before continuing, it is important to understand Hex-Rays maturity levels. When a binary is loaded into IDA Pro, the application will perform distinct layers of code analysis and optimization, referred to as maturity levels. One layer will detect shellcode, another optimizes it into blocks, another determines global variables, and so on.

The optinsn_t::func callback function is called in maturity levels from MMAT_ZERO (microcode does not exist) to MMAT_GLBOPT2 (most global optimizations completed). During the callback, opaque predicates pattern-matching functions are called. If the code pattern is matched with the definitions, it is replaced with another expression for the deobfuscation. This is important to perform in each maturity level as the obfuscated code could be modified or removed as the code becomes more optimized. We mainly defined two patterns for analysis of the ANEL sample.

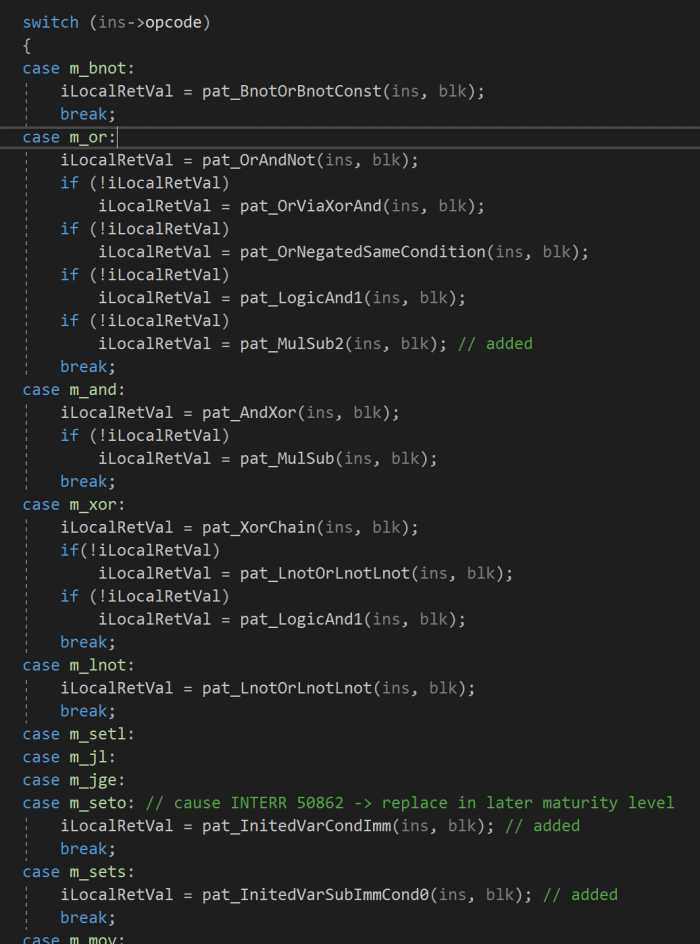

Figure 3: Opaque predicates pattern-matching functions switch.

Figure 3: Opaque predicates pattern-matching functions switch.

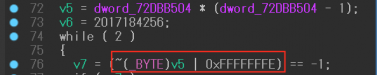

Figure 4 shows an example of one of the opaque predicates patterns used by ANEL.

![]() Figure 4: Opaque predicates pattern 1.

Figure 4: Opaque predicates pattern 1.

The global variable value dword_745BB58C is either even or odd, so dword_745BB58C * (dword_745BB58C - 1) is always even. This results in the lowest bit of the negated value becoming 1. Thus, OR by -2 (0xFFFFFFFE) will always produce the value -1.

In this case, the pattern-matching function replaces dword_745BB58C * (dword_745BB58C - 1) with 2.

Another pattern is shown in Figure 5.

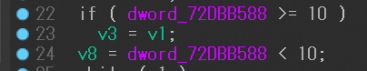

Figure 5: Opaque predicates pattern 2.

Figure 5: Opaque predicates pattern 2.

The global variable value dword_72DBB588 is always 0 because the value is not initialized (we can check it using the is_loaded API) and only has read accesses. So the pattern-matching function replaces the global variable with 0.

There are some variants with this pattern (e.g. the variable - 10 < 0), where the immediate constant may be different, such as 9.

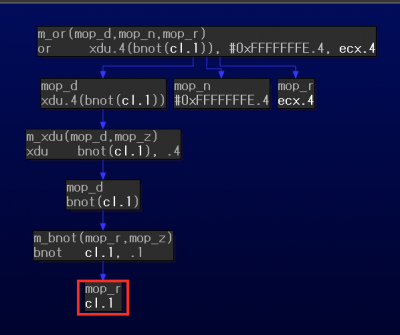

We also observed a pattern that was also using an eight-bit portion of the register. In the example shown in Figures 6 and 7, the variable v5 in pseudocode is a register operand (cl) in microcode. We need to check if the value comes from the result of x * (x - 1).

Figure 6: Register operand (pseudocode) in pattern 1.

Figure 6: Register operand (pseudocode) in pattern 1.

Figure 7: Register operand (microcode) in pattern 1.

Figure 7: Register operand (microcode) in pattern 1.

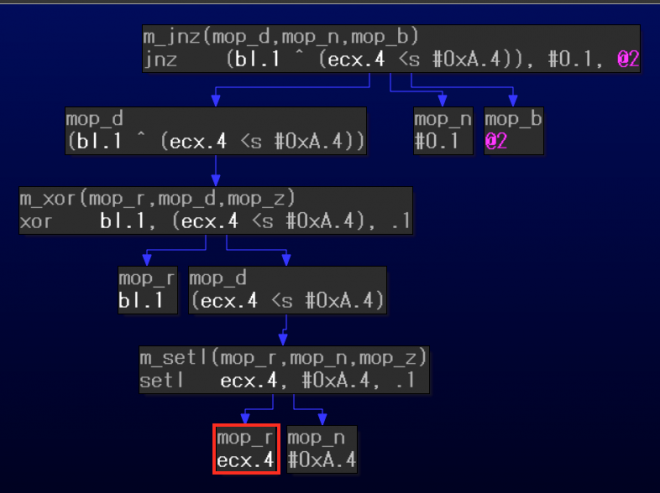

In another example, the variable v2 in pseudocode is a register operand (ecx) in microcode. We have to validate if a global variable with the above-mentioned conditions is assigned to the register.

Figure 8: Register operand (pseudocode) in pattern 2.

Figure 8: Register operand (pseudocode) in pattern 2.

Figure 9: Register operand (microcode) in pattern 2.

Figure 9: Register operand (microcode) in pattern 2.

Data-flow tracking code was added to detect these use-cases. The added code requires that the mblock_t pointer information is passed from the argument of optinsn_t::func to trace back previous instructions using the mblock_t linked list. However, the callback returns NULL from the mblock_t pointer if the instruction is not a top-level one. For example, Figure 9 shows jnz (m_jnz) as a top-level instruction and setl (m_setl) as a sub-instruction. If setl is always sub-instruction during the optimization, we never get the pointer. To handle this type of scenario, the code was modified to catch and pass the mblock_t of the jnz instruction to the sub-instruction.

The original implementation calls the optblock_t::func callback function in the MMAT_LOCOPT (local optimization and graphing are complete) maturity level. Rolles previously described the unflattening algorithm in a Hex-Rays blog. For brevity, I will quickly cover some key points in order to understand the algorithm at a high level.

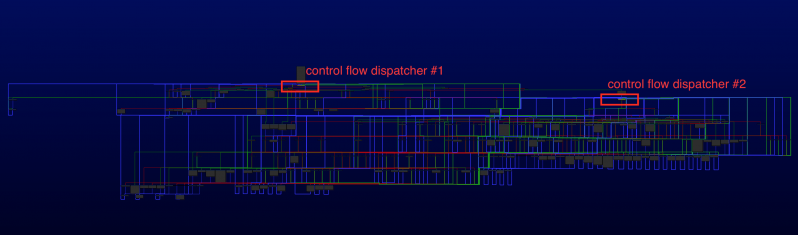

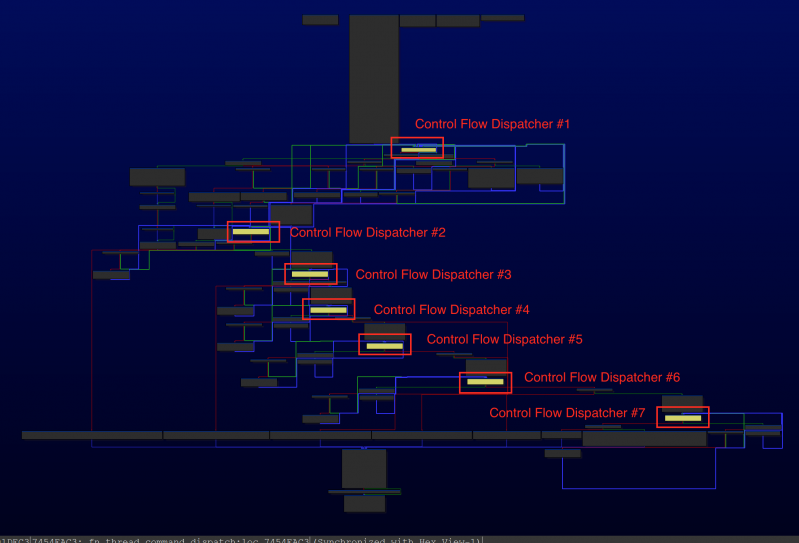

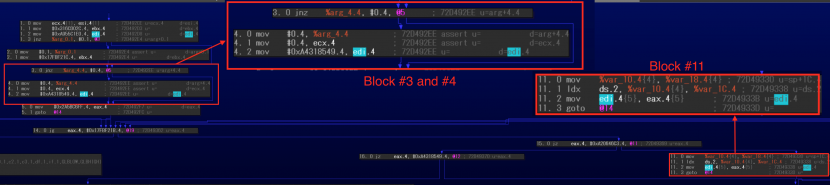

Normally, the call flow graph (CFG) of a function obfuscated with control flow flattening has a loop structure that starts with the yellow-coloured ‘control flow dispatcher’ shown in Figure 10 after the First Block.

Figure 10: Function obfuscated with control flow flattening.

Figure 10: Function obfuscated with control flow flattening.

The original code is separated into the orange-coloured ‘first block’ and the green-coloured flattened blocks. The analyst is then required to resolve the correct next block and modify the destination accordingly.

The next portion of the first block and each flattened block is decided by a ‘block comparison variable’ with an immediate value. The value of the variable is assigned to a specific register in each block then compared in a control flow dispatcher and other condition blocks.

Figure 11: Block comparison variable example (blue-highlighted eax in this case).

Figure 11: Block comparison variable example (blue-highlighted eax in this case).

If the variable registers for the comparison and assignment are different, the assignment variable is called the ‘block update variable’ (which will be described later).

The algorithm looks straightforward. However, some portions of the code had to be modified in order to correctly deobfuscate the code. This is detailed further below.

As previously described, the original implementation of the code only works in the MMAT_LOCOPT maturity level. Rolles said this was to handle another obfuscation called ‘Odd Stack Manipulations’, which he refers to in his blog. However, the unflattening of the ANEL code had to be performed in the later maturity level since the assignment of block comparison variables depends heavily on opaque predicates.

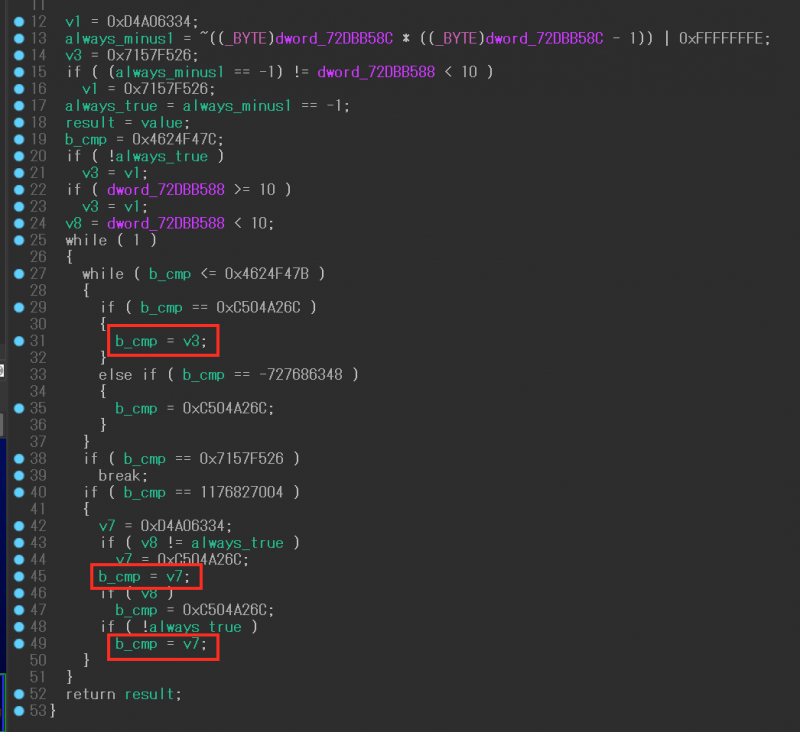

As an example, in the obfuscated function shown in Figure 12, the v3 and v7 variables are assigned to the block comparison variable (b_cmp). The values are dependent on the results of the opaque predicates.

Figure 12: Simple obfuscated function example.

Figure 12: Simple obfuscated function example.

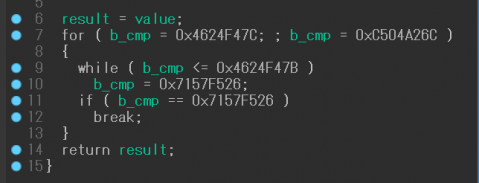

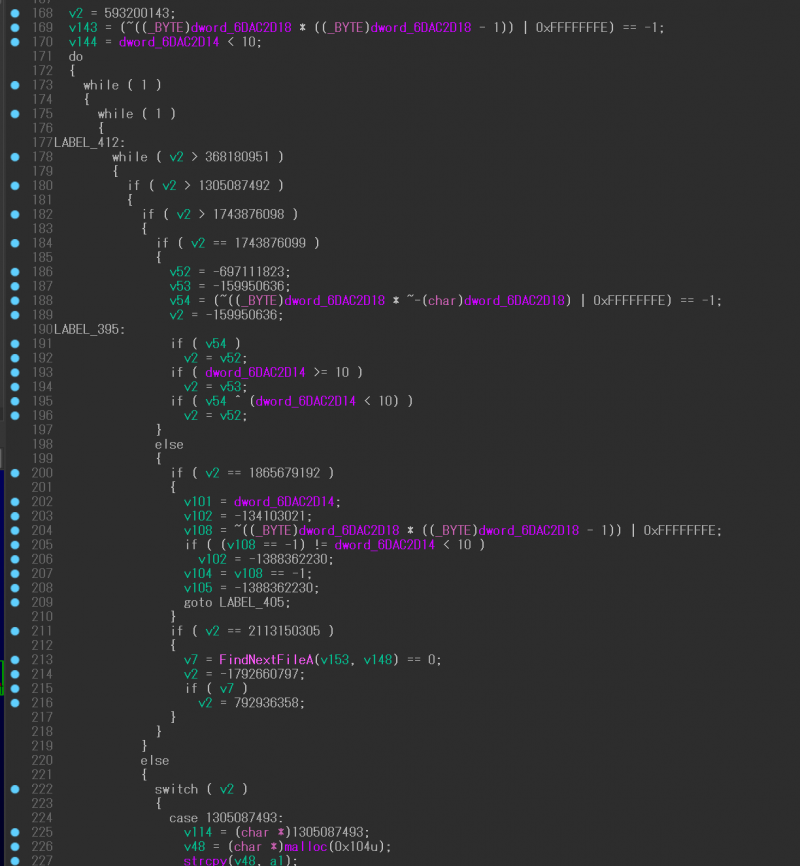

Once the opaque predicates are broken, the loop code becomes simpler, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13: Simple obfuscated function example (opaque predicates deleted).

However, unflattening the code in later maturity levels like MMAT_GLBOPT1 and MMAT_GLBOPT2 (first and second pass of global optimization) caused additional problems. The unflattening algorithm requires mapping information between the block comparison variable and the actual block number (mblock_t::serial) used in the microcode. In later maturity levels, some blocks are deleted by the optimization after defeating opaque predicates, which removes the mapping information.

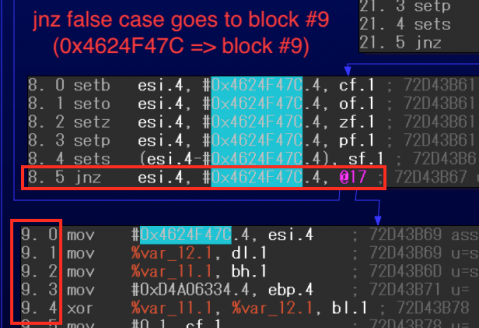

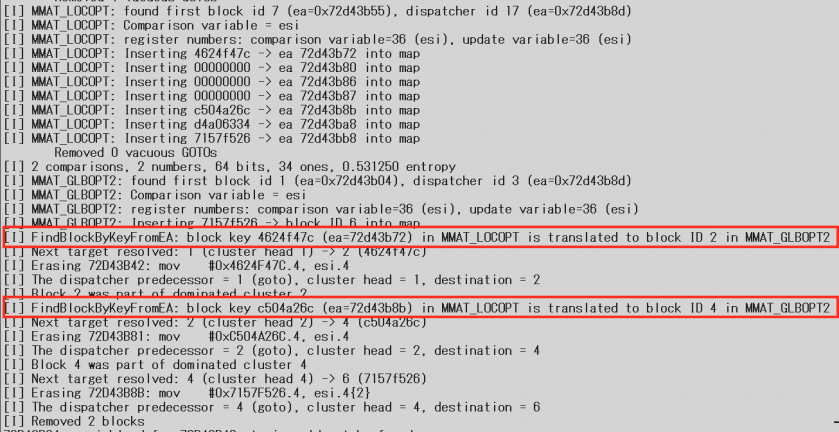

In the example shown in Figure 14, the blue-highlighted immediate value 0x4624F47C is assigned to the block comparison variable in the first block. The mapping can be created by checking the conditional jump instruction (jnz) in MMAT_LOCOPT.

Figure 14: Mapping between block comparison variable 0x4624F47C and block number 9.

Figure 14: Mapping between block comparison variable 0x4624F47C and block number 9.

On the other hand, there is no mapping information in MMAT_GLBOPT2 because the condition block that contains the variable has been deleted. So the next block of the first one in the level cannot be determined.

To resolve this issue, the code was written to link the block comparison variable and block address in MMAT_LOCOPT, as the block number is changed in each maturity level. If the code can’t determine the mapping in later maturity levels, it attempts to guess the next block number based on the address, considering each block and instruction address. The guessing is not 100% accurate, however it works for nearly all of the obfuscated functions tested.

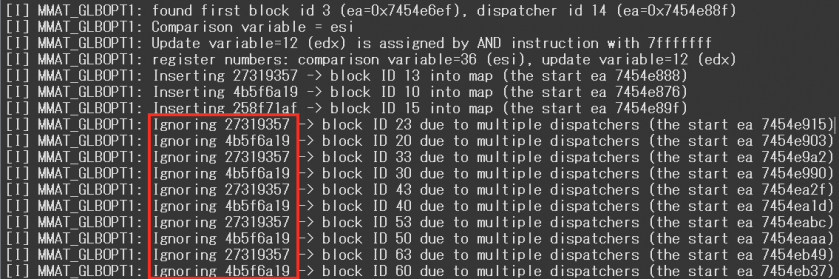

Figure 16: The output log showing block address and number translation.

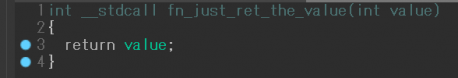

Figure 17 shows the final result of the deobfuscation in this case. The function just returns the argument value.

Figure 17: The result of the deobfuscation.

Figure 17: The result of the deobfuscation.

Though the original implementation assumes an obfuscated function has only one control flow dispatcher, some functions in the ANEL sample have multiple control dispatchers. Originally, the modified code called the optblock_t::func callback in MMAT_GLBOPT1 and MMAT_GLBOPT2, as the result was not correct in MMAT_CALLS (detecting call arguments). However, this did not work for functions with three or more dispatchers. Additionally, the Hex-Rays kernel doesn’t optimize some functions in MMAT_GLBOPT2 if it judges that optimization within the level is not required. In this case, the callback is executed just once in the implementation.

To handle multiple control flow dispatchers, a callback for decompiler events was implemented. The code catches the ‘hxe_prealloc’ event (according to Hex-Rays, this is the final event for optimizations) then calls the optblock_t::func callback. Typically, this event occurs a few to several times, so the callback can deobfuscate multiple control flow flattenings. Other additional modifications were made to the code (e.g. writing a new algorithm for finding the control flow dispatcher and first block, validating a block comparison variable, and so on).

Figures 18-23 show the functions with multiple control flow dispatchers that can be unflattened after the modification. Figures 18-20 show the case of two control flow dispatchers; Figures 21-23 show the case of seven control flow dispatchers.

Figure 18: Example #1 with two control flow dispatchers (graph).

Figure 18: Example #1 with two control flow dispatchers (graph).

Figure 19: Example #1 with two control flow dispatchers (before).

Figure 19: Example #1 with two control flow dispatchers (before).

Figure 20: Example #1 with two control flow dispatchers (after).

Figure 21: Example #2 with seven control flow dispatchers (graph).

Figure 21: Example #2 with seven control flow dispatchers (graph).

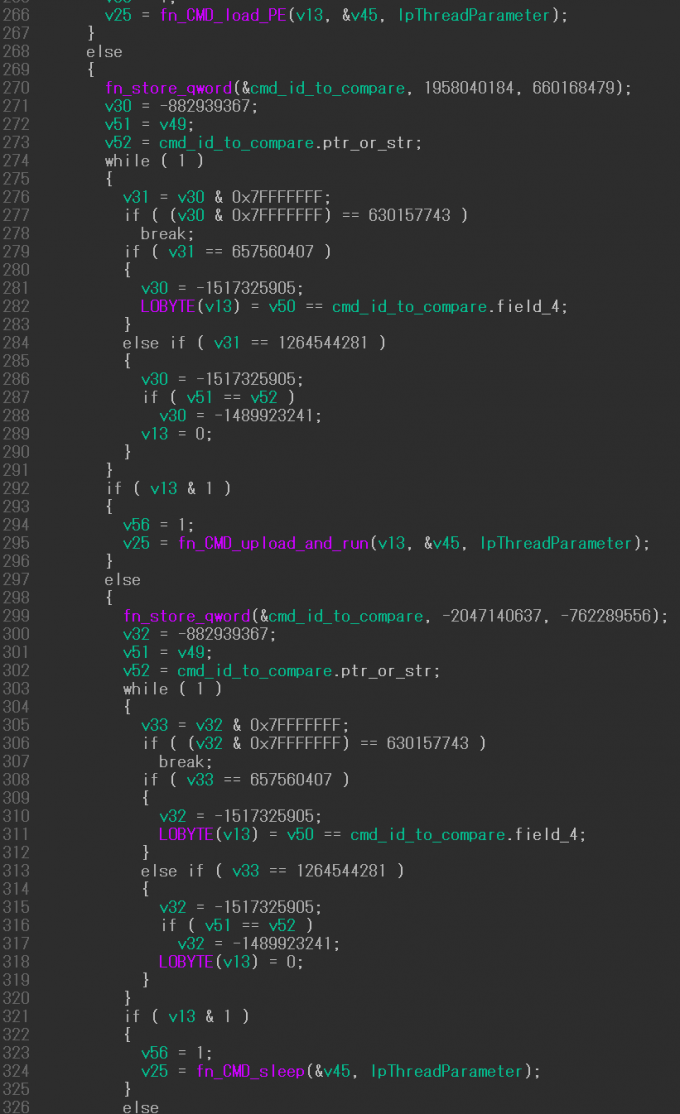

Figure 22: Example #2 with seven control flow dispatchers (before).

Figure 22: Example #2 with seven control flow dispatchers (before).

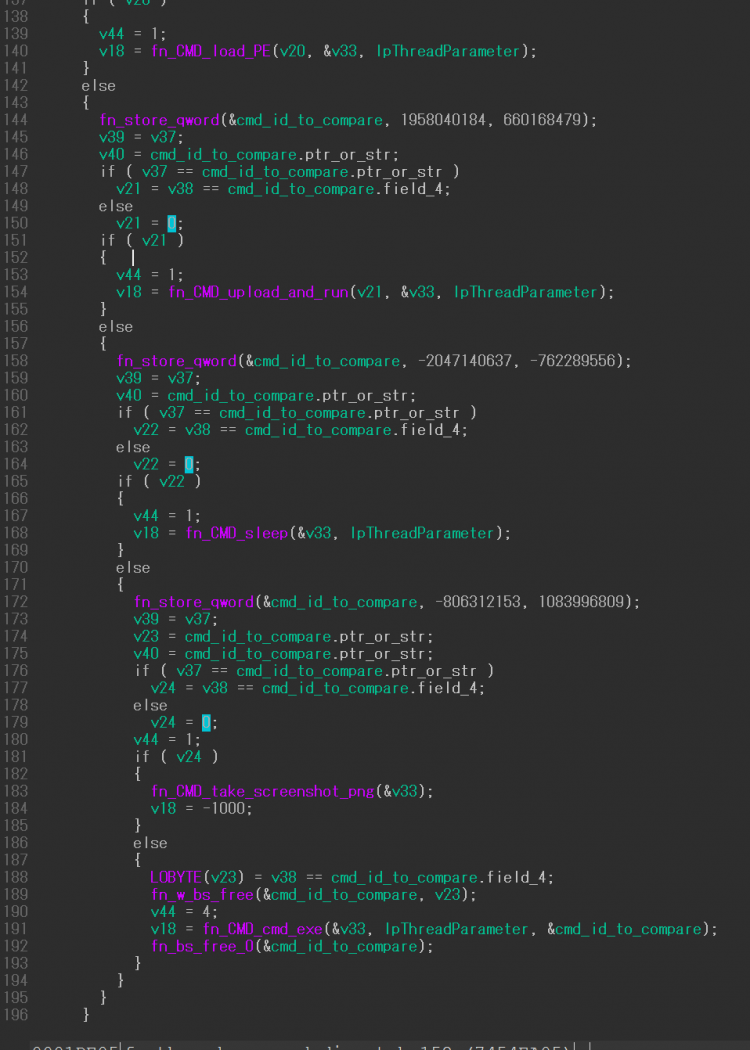

Figure 23: Example #2 with seven control flow dispatchers (after).

Figure 23: Example #2 with seven control flow dispatchers (after).

Figure 24: Ignoring duplicated block comparison variables.

Normally, block comparison variables used by the control flow flattening are unique in a function. Therefore, block numbers corresponding to the variables can be determined uniquely as well. However, the function in the latter case contains duplicated block comparison variables due to multiple dispatchers. The modified code detects the duplications and applies the most likely variable.

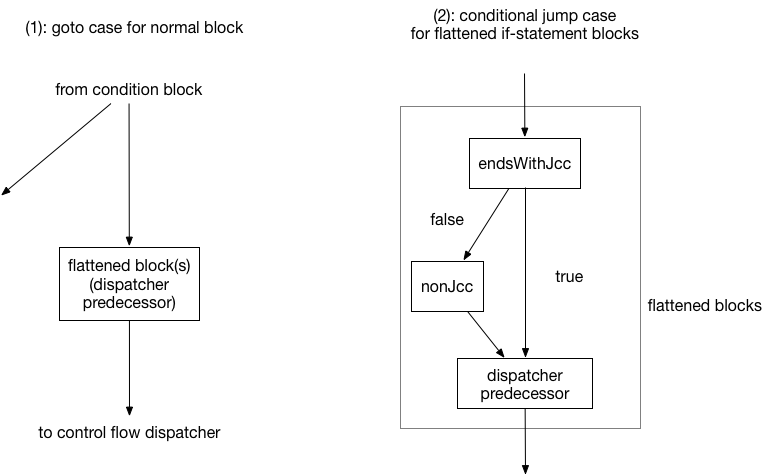

As shown in Figure 25, the original implementation supports two cases (1)-(2) of flattened blocks to find a block comparison variable for the next block (the cases are then simplified). In the second case, the block comparison variable is searched in each block of endsWithJcc and nonJcc. If the next block is resolved, the CFG (specifically mblock_t::predset and mblock_t::succset) and the destination of the goto jump instruction are updated.

Figure 25: Originally supported two cases of blocks.

We found and implemented three more cases in the ANEL sample. Of these, two cases (3)-(4) are shown in Figure 26.

Figure 26: Newly supported two cases of blocks.

Figure 26: Newly supported two cases of blocks.

The code tracks the block comparison variable in each predecessor and more (if there are any conditional blocks before the predecessor) to identify each next block for unflattening.

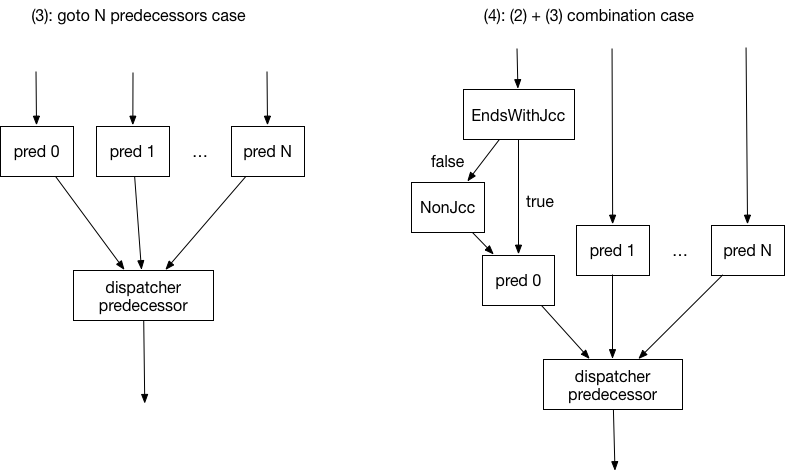

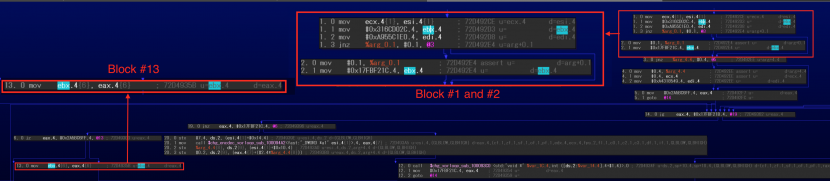

In the jump case (5) that was newly implemented, the block comparison variables are not assigned in the flattened blocks but rather the first blocks according to a condition. For example, the microcode graph depicted in Figure 27 shows that edi is assigned to esi (the block comparison variable in this case) in block number 7, but the edi value is assigned in block numbers 1 and 2.

Figure 27: Newly supported case (assigned in first blocks).

If the immediate value for the block comparison variable is not found in the flattened blocks, the new code tries to trace the first blocks to obtain the value and reconnects block numbers 1 and 2 as successors of block number 7, in addition to the normal operations mentioned in the original cases.

Another example function, shown in Figures 28 and 29, did the same processing twice.

Figure 28: Newly supported case (assigned in first blocks twice #1).

Figure 28: Newly supported case (assigned in first blocks twice #1).

Figure 29: Newly supported case (assigned in first blocks twice #2).

Figure 29: Newly supported case (assigned in first blocks twice #2).

In this case, the code parses the structure in the first blocks then reconnects each conditional block under the flattened blocks (#1 and #2 as successors of #13, #3, and #4 as successor of #11).

Last, but not least, in all cases described here, the tail instruction of the dispatcher predecessor can be a conditional jump like jnz, not just goto. The modified code checks the tail instruction and if the true case destination is a control flow dispatcher, it updates the CFG and the destination of the instruction. However, the handling of conditional jumps in cases (2)-(4) requires more complicated operations and the latest IDA (version 7.2) at the time was not able to process them. It will be detailed below.

The following changes are minor compared with the above referenced ones.

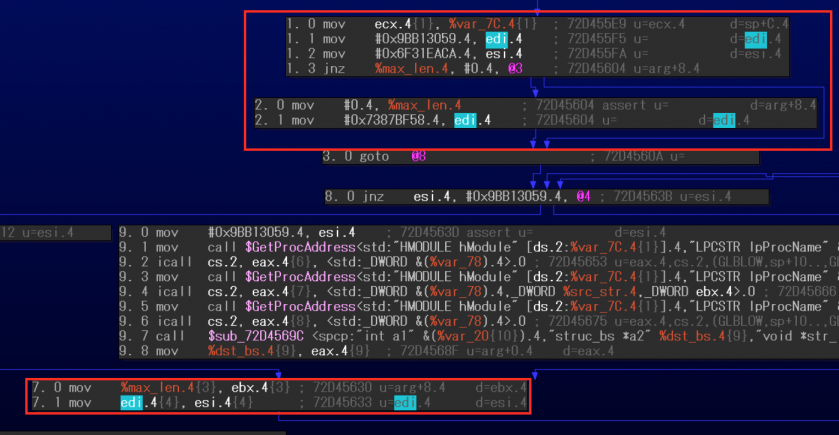

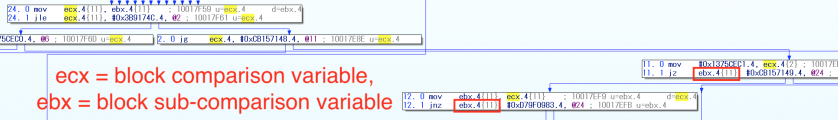

Additionally, two more changes were introduced in regards to the block comparison/update variables referenced in the overview. First, some functions in the ANEL sample utilize a block update variable, however the assignment is a little bit tricky, as shown in Figure 30.

Figure 30: Block update variable usage with and instruction.

Figure 30: Block update variable usage with and instruction.

By using the and instruction, the immediate values used in comparison look different from assigned ones. Second, in a different case, a small number of functions utilize dual block comparison variables, as shown in Figure 31.

Figure 31: A function with dual block comparison variables (microcode).

The modified code will consider both of the cases.

The modified tool was tested on IDA 7.2 with an ANEL 5.4.1 payload dropped from a malicious document with the following hash (previously reported by FireEye [5]): 3d2b3c9f50ed36bef90139e6dd250f140c373664984b97a97a5a70333387d18d

The current code was able to deobfuscate 92% of the obfuscated functions that we encountered. In the 8% of cases where deobfuscation failed, the failure was caused by any of the three following issues:

The first issue has already been resolved but may be problematic in the future as the approach is not 100% accurate. The guessing algorithm will be improved every time a new issue in it is found. However, the other issues were reported to Hex-Rays and resulted in an IDA 7.3 beta version to address them. In the following sections, the issues and their solutions will be discussed.

Additionally, the tool also worked for the following ANEL 5.5.0 rev1 payload loader DLL published by Secureworks [6]: f333358850d641653ea2d6b58b921870125af1fe77268a6fdfeda3e7e0fb636d.

The IDA 7.2 decompiler does not propagate aliased stack slots. In the example shown in Figure 32, the variables true1 and true2 are aliased. Thus the results after breaking opaque predicates are not propagated even if an immediate value 1 is assigned to them.

Figure 32: Opaque predicates deobfuscation result propagation failure on IDA 7.2.

Figure 32: Opaque predicates deobfuscation result propagation failure on IDA 7.2.

The IDA 7.3 beta decompiler resolving this issue is able to deobfuscate the function correctly, as shown in Figure 33.

Figure 33: Opaque predicates deobfuscation result propagation success on IDA 7.3 beta.

Figure 33: Opaque predicates deobfuscation result propagation success on IDA 7.3 beta.

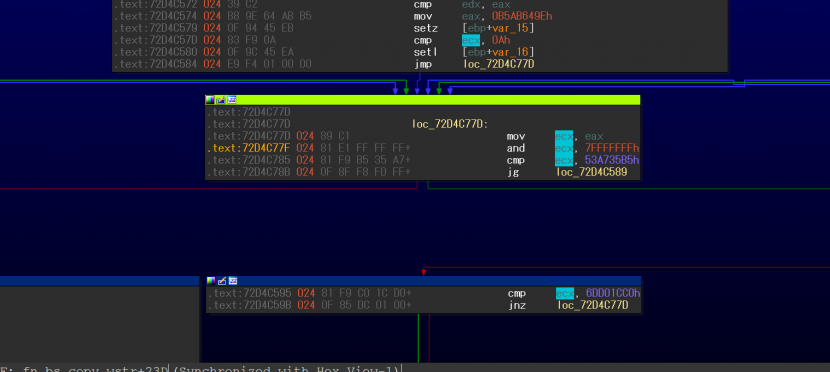

As described previously, more complicated operations are required to handle the cases (2)-(4) of flattened blocks if the dispatcher predecessor’s tail instruction is a conditional jump. For instance, in case (3), let’s consider a dispatcher predecessor with two predecessors.

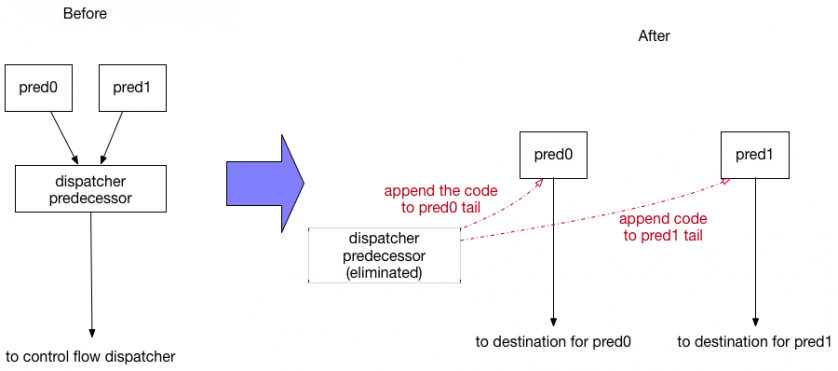

Handling a goto case (unconditional jump case, in Figure 34) is straightforward. The implementation searches block comparison variables in pred0 and pred1 (predecessor #0 and #1) separately then resolves the next block numbers in microcode according to the variables. After that, it changes each destination in both CFG and instruction levels while appending the codes of a dispatcher predecessor to each predecessor. As a result, the dispatcher predecessor block will be eliminated.

Figure 34: Before and after goto case with two predecessors.

Figure 34: Before and after goto case with two predecessors.

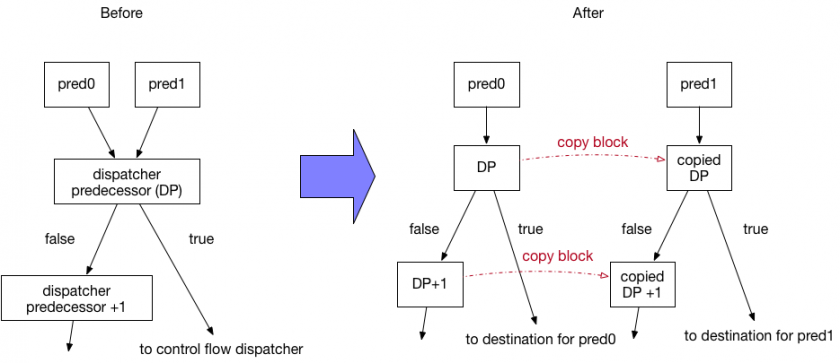

However, in a conditional jump (Figure 35), the destination of the true case is replaced with resolved next block numbers, however two blocks of the dispatcher predecessor and its false case block should be copied for pred1 as a false case block number must be its conditional jump’s block number plus 1 in imicrocode (dispatcher predecessor + 1 in this case). Therefore, the false case block cannot be shared by the two predecessors.

Figure 35: Before and after conditional jump case with two predecessors.

Additionally, in Figure 34, if pred0 or pred1 contains a conditional jump, the dispatcher predecessor will be copied in the same way regardless of its tail instruction because a conditional jump instruction cannot be overwritten by a goto one.

IDA 7.2 doesn’t permit overlapped instructions by copying a microcode block (mblock_t) as many instructions must have distinct addresses. Duplicated instructions are allowed in IDA 7.3 by clearing the flag MBA2_NO_DUP_CALLS. The latest code utilizes its flag and handles cases (2)-(4) with conditional jumps correctly.

Specifically, the code makes an empty block by using the mbl_array_t::insert_block API then copies instructions and other information such as flags and start/end addresses from the original block. The code also has to adjust CFGs and instructions of the blocks, passing control to the exit block whose block type is BLT_STOP if CFG updates by the API usage or the unflattening code cause a conflicted situation.

Workaround in control flow unflattening failure

If an obfuscated function contains any of the issues described in this section, the decompiled code result may be paradoxical or lose multiple code blocks. In this case, try to use the following IDAPython command in the output window:

idc.load_and_run_plugin("HexRaysDeob", 0xdead)

The command will instruct the code to execute only opaque predicates deobfuscation in the current selected function. This allows an analyst to quickly check if there are any lost blocks through control flow unflattening. For instance, Figures 36 and 37 show how the pseudocode changes in one of the failure cases.

Figure 36: One failure case pseudocode (before).

Figure 36: One failure case pseudocode (before).

Figure 37: One failure case pseudocode (after).

Figure 37: One failure case pseudocode (after).

After the check, the original result can be restored by using the following command:

idc.load_and_run_plugin("HexRaysDeob", 0xf001)

Compiler-level obfuscations like opaque predicates and control flow flattening are starting to be observed in the wild and will be a challenge for malware analysts and researchers. Currently, malware with these obfuscations is limited, however TAU expects not only APT10 but also other threat actors to start to use them. In order to break the techniques, we have to understand both of the obfuscation mechanisms and the disassembler tool internals before we can automate the process.

TAU modified the original HexRaysDeob plug-in to make it work for APT10 ANEL obfuscations. The modified code is available publicly [7]. The summary of the modifications is:

This tool works for most obfuscated functions in the tested samples. This implementation can deobfuscate approximately 92% of encountered functions. Additionally, most of the failed functions will be properly deobfuscated in IDA 7.3.

It should be noted that the tool may not work for updated versions of ANEL if they are compiled with different options of the obfuscating compiler. Testing in multiple versions is important, so TAU is looking for newer version ANEL samples. Please reach out to our unit if you have relevant samples or need assistance in deobfuscating the codes.

It’s difficult to create a generic tool that can defeat every compiler-level obfuscated binary but experience and knowledge about IDA microcode can be useful for additional new tools.

First I acknowledge Hex-Rays for supporting the research patiently. Next, I appreciate Rolf Rolles for releasing the original version of HexRaysDeob. Last but not least, I would like to thank TAU’s members, especially Jared Myers and Brian Baskin, for proofreading and giving a lot of feedback.

[1] Diplomats in Eastern Europe bitten by a Turla mosquito. ESET. https://www.welivesecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/ESET_Turla_Mosquito.pdf.

[2] APT10によるANELを利用した攻撃手法とその詳細解析. Secureworks. https://jsac.jpcert.or.jp/archive/2019/pdf/JSAC2019_6_tamada_jp.pdf.

[3] Rolles, R. Hex-Rays Microcode API vs. Obfuscating Compiler. http://www.hexblog.com/?p=1248.

[4] Rolles, R. Hex-Rays microcode API plugin for breaking an obfuscating compiler. https://github.com/RolfRolles/HexRaysDeob.

[5] APT10 Targeting Japanese Corporations Using Updated TTPs. FireEye. https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2018/09/apt10-targeting-japanese-corporations-using-updated-ttps.html.

[6] ANELで日本を標的とした攻撃活動を行う攻撃者グループ BRONZE RIVERSIDEに関する調査報告. Secureworks. https://www.secureworks.jp/resources/at-bronze-riverside-updates-anel-malware.

[7] HexRaysDeob for APT10 ANEL. Carbon Black. https://github.com/carbonblack/HexRaysDeob.