2011-11-01

Abstract

Despite the Windows versions of Zeus and SpyEye now sharing source code, Zitmo and Spitmo - the mobile components of each - have nothing in common at the code level. Spitmo was created from scratch solely for the purpose of stealing mTANs. Mikko Suominen has all the details.

Copyright © 2011 Virus Bulletin

In late 2010 the first mobile trojan that intercepted mobile transaction authentication numbers (mTANs) was discovered. That trojan, Zitmo (Zeus In The MObile), was joined at the hip with Zeus to defeat two-factor authentication of online banking [1], [2]. Zeus received competition from [3] and was then merged with the SpyEye trojan [4], so it did not come as a great surprise when in March 2011 Spitmo arrived. Spitmo is the Symbian component of SpyEye, created for the same purpose as Zitmo was for Zeus. This article presents the technical details of Spitmo and offers an insight into reconstructing its high-level language constructs, giving a new view to reverse engineering a Symbian trojan.

To strengthen the security of their online banking systems many banks have introduced two-factor authentication using a mobile phone. When a customer carries out a transaction using online banking, an SMS containing an mTAN is sent to the customer’s mobile phone. The transaction cannot be completed until the mTAN is entered into the online-banking system.

As mentioned in the introduction, the first malware family to attack mTANs was Zitmo, the mobile counterpart for the Windows-based Zeus trojans. SpyEye emerged first as a competitor to the Zeus toolkit, and later the Zeus source code was bought by the SpyEye author and the two families were merged. In March 2011, a mobile phone component to accompany the Windows-based SpyEye trojan was discovered. The phone component of the trojan targeted the Symbian operating system and was named Trojan:SymbOS/Spitmo.A (SPyeye In The MObile).

Even though the Windows versions of Zeus and SpyEye now share source code [4], Zitmo and Spitmo have nothing in common at the code level. Zitmo is based on commercial spyware [1], but Spitmo has been created from scratch solely for the purpose of stealing mTANs.

In the Spitmo.A attack, SpyEye injected banking web pages with fields requesting the victim’s IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identity) and mobile phone number. The injected dialogue also informed the user that ‘a certificate’ (i.e. Spitmo) would be generated and that the process could take up to three days. This delay was due to the way in which the trojan was digitally signed. Since Symbian S60 third edition, all Symbian applications must be digitally signed in order for the phone to install them. Spitmo was signed with a developer certificate, which allows software developers to sign their Symbian installers themselves without uploading them to the Symbian Signed service. However, applications signed with a developer certificate can only be installed on phones whose IMEI is listed in the developer certificate itself. It was for this reason that the IMEI was requested by the Windows component of SpyEye. As the attackers received IMEIs from new victims, they requested new developer certificates that included the new IMEIs. The certificate was probably acquired through the OPDA website (http://cer.opda.cn at the time of the attack), which is an unofficial source for Symbian developer certificates. The delay in receiving the new certificates explains the message stating the three-day delay.

Spitmo was delivered to victims in an installer that was named so that it would look like a certificate. The trojan was in a package named ‘Sms’ and had a single malicious binary (Sms.exe).

The trojan is configured by settings.dat, which among other things defines where the stolen data is uploaded and which SMS messages are stolen. It also contains a file named first.dat, which is used to check if this is the first time the trojan has been executed; a resource file ([E13D4ECD].rsc) to launch the trojan every time the phone is started; and an embedded package called ‘SmsControl’. The only thing SmsControl does is display a message showing ‘the serial number of the security certificate’, thus completing the illusion that a certificate really has been received from the bank. The file name ‘SmsControl.exe’ is one similarity between Spitmo and Zitmo – the main executable of a variant of Zitmo discovered in February 2011 used the same name.

Symbian C++ is heavily object-oriented and thus to gain a thorough understanding of Spitmo we need to look at what classes it contains and understand their structure – namely their member variables and functions.

The interception and theft of mTANs directly involves four classes:

CSms

CSettings

CDataQueue

CHttpPost

The interception of mTANs is performed in the class called CSms. This class inherits and implements the Symbian mixin class MMsvSessionObserver. MMsvSessionObserver ‘Provides the interface for notification of events from a Message Server session’ [6]. In other words, by inheriting and implementing the MMsvSessionObserver class, a Symbian application can monitor all events related to messaging (SMS, MMS, email).

The member variables of a class can be deduced when offsets into the object are loaded or stored to registers and from their subsequent use. API function parameters and return values are especially informative as their types can be checked from the SDK documentation. For example, Figure 1 shows a piece of code which is part of the constructor for CSms. We see that the return value of CMsvSession::OpenAsyncL is stored to offset 0x4 of CSms as its first member variable. From the SDK documentation we can see that the function returns a pointer to a CMsvSession [5], therefore the first member variable of CSms is a pointer to a CMSvSession object. The parameter of the function is also one way to confirm that CSms inherits MMsvSessionObserver. CSms must be a subclass of MMsvSessionObserver as OpenAsyncL requires an MMsvSessionObserver object as parameter [5]. By continuing this process and by combining the information with the reverse engineering of different member functions, most member variables for Spitmo’s classes can be resolved.

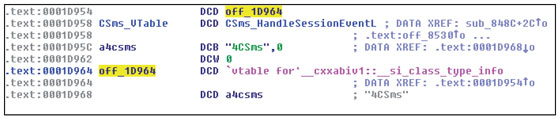

The member functions for Spitmo’s classes can be found from its class information. Figure 2 shows the class information for CSms. An offset that references __si_class_type_info or __vmi_class_type_info marks the beginning of the class information. The information block begins with a table of pointers to the member functions of that class (vtable).

Figure 2. Class information for CSms (vtable offset and member function have been renamed manually).

As can be seen from Figure 2, CSms has just a single member function, which therefore must be HandleSessionEventL() as it is the only member function of MMsvSessionObserver and must be implemented for the class to function [6]. With the member variables and function now solved, the header file for CSms can be reconstructed (the variable names are, of course, not the original ones).

Figure 3 shows the member variables and member function of Spitmo’s CSms class. Of the member variables, all but iError and iErrorCounter can be deduced from the constructor and different API calls in CSms::HandleSessionEventL().

The class information can also be used to locate the constructor for that class. The first four bytes of an object will hold the address of the vtable for that class. For that reason the constructor will have a reference to the vtable as it stores it to the objects of that class. The function that references the vtable and stores a pointer to it to the start of a freshly allocated heap block is the second-stage constructor of the class. The second-stage constructor is called by the first-stage constructor, which performs the heap allocation.

These steps were repeated for Spitmo’s classes to reveal what exactly it steals and how it performs the theft.

From the reconstructed header file it is already clear that CSms deals only with messages and uses objects of other user code classes to access settings and perform an HTTP post. Next, the only member function of the class will be analysed to reveal the details of the mTAN theft.

MMsvSessionObserver::HandleSessionEventL() is called by the operating system when a messaging event has happened so that the class that implements MMsvSessionObserver can handle the event. CSms::HandleSessionEventL() receives the following as parameters [6]:

TMsvSessionEvent, the type of event

CMsvEntrySelection, an array of IDs of the affected messages

TMsvId, the ID of the parent of the message (the folder of the message).

Spitmo is interested in three different kinds of messaging events as it compares the TMsvSessionEvent to three different values: EMsvEntriesCreated (numerical value 0), EMsvCloseSession (7), and EMsvServerReady (8). Of these, only EMsvEntriesCreated is related to individual messages, the other two being status notifications from the messaging server. When Spitmo receives an event notifying it of a new messaging entry, HandleSessionEventL() will call another subroutine to further process the message. TMsvId and CMsvEntrySelection are passed to the subroutine as parameters. TMsvId will be compared to KMsvGlobalInBoxIndexEntryId (numerical value 0x1002), and the message is further processed only if the message is in the inbox – meaning that Spitmo is only interested in incoming messages. The other parameter, CMsvEntrySelection, contains an array of message entry IDs. Spitmo will iterate through this array and from each message identified as an SMS message, extract the message body (with CBaseMtm::Body()) and the phone number from which the message was sent (using CSmsPDU::ToFromAddress()). The decision on whether or not to steal a particular message is made by a member function of CSettings.

Member functions are called with a BLX R3 instruction and the type of object pointed to by R0 defines what class the member function belongs to. The type of object is known after figuring out the member variables of CSms and their offsets within the CSms object. Figure 4 shows the sequence of instructions used for member function calls in Spitmo. An offset into the vtable for that class is clearly visible so finding the correct function from the vtable is trivial. Additional dereferencing instructions are among the code when the member function in question belongs to an object that is a member of some other object.

The function (at address 0xF058) receives the phone number from which the SMS came and the message body as parameters. The function will return 1 if the value of tag P5 from the settings.dat file is found in the message body. (The content of settings.dat will be covered in more detail later.)

Interestingly, the phone number is not used by the target comparison function in any way. Is this an indication that the attackers first planned to identify the mTAN messages based on phone number and not message content? And is this why the parameter still remained in the source code when Spitmo was compiled?

If the message is identified as an mTAN, the message body is stored in an instance of CDataQueue. CDataQueue is a simple container object that holds the stolen messages in an array together with a timestamp of when they were stored to the queue. As its member functions CDataQueue offers an interface to add, remove and retrieve items or determine the number of items in the queue. Messages identified as containing mTANs are then deleted by Spitmo to hide the fact that a banking transaction is being carried out without the victim’s knowledge. After stealing and deleting the message Spitmo calls a member function of CHttpPost, which will form a multipart message together with the victim’s IMEI and phone number, the stolen message, and the time when the http data is formed for all items in the CDataQueue object. The multipart message is then promptly posted to a remote server.

The URL to which the data is uploaded is defined in tag P3 of settings.dat. Uploading the stolen data is not the only HTTP connection the trojan makes, as at regular intervals it will contact the same URL and send the IMEI, phone number, operating system version, phone model and time on the phone as URL parameters. The first connection is made shortly after infection, but can be changed with tag P13 in the settings.dat file. The connection is then repeated with intervals defined in tag P4 of settings.dat.

Settings.dat is the configuration file for the trojan and is in XML format, where the names of the tags can range from P0 to P15. The configuration file is parsed by CSettingsLoader and an instance of CSettings class will store the values as its member variables.

Trojan:SymbOs/Spitmo.A has five different values in its settings file, with tags ranging from P3 to P7. Figure 5 shows the content of the settings file that was included in the installer of Spitmo.A. The remaining values are not required for the trojan to work and many of them are assigned default values by the constructor of CSettings if the tags are not found in settings.dat. Table 1 shows the purposes of all tags found in Spitmo.A’s configuration file and several additional ones that were reverse engineered during analysis.

| Tag | Purpose | Default value |

| P0 | 1 | |

| P1 | If set to 0 the trojan will be disabled as it exits after creating the CSettings object and checking this value. | 1 |

| P2 | If set to 1 logging will be enabled. The content of stolen messages will be written to c:\data\sms.log, together with a time stamp. | 0 |

| P3 | URL to which stolen data will be sent. | |

| P4 | Interval in minutes between repeating contact with the remote server. This does not define how often stolen SMS messages are relayed to the attacker. | 60 |

| P5 | mTAN identification string. If this is found in an SMS, the message content is stolen and the SMS is deleted. | |

| P6 | URL from which an installer can be downloaded. The name of the class handling the download (CHttpUpdate) suggests the installer will be a new version of Spitmo and not additional malware. | |

| P7 | Path to which the downloaded installer is saved on the phone. | |

| P8 | 5 | |

| P9 | 2 | |

| P10 | Delay in milliseconds between retries if CSms::HandleSessionEventL() encounters errors. | 500,000 |

| P11 | Maximum number of retries in CSms::HandleSessionEventL() before moving on to the next message. | 9 |

| P12 | 15 | |

| P13 | Delay in seconds before making first contact with server after infection. | 10 |

| P14 | 3 | |

| P15 | 3 |

Table 1. Definitions for different XML tags in settings.dat.

The method of social engineering (pretending to be a certificate) and file names used by Spitmo suggest that its authors are at least superficially familiar with Zitmo. However, its implementation is completely different and it uses a simple method offered by the Symbian API to monitor new incoming SMS messages. As the target for the theft is defined through a configuration file, the same trojan could be used to attack any bank whose mTAN messages have some constant part that can be used to identify them. The use of HTTP traffic instead of sending SMS messages to deliver the mTANs to the attacker makes the trojan appear less suspicious as, although not extremely rare in legitimate Symbian applications, SMS sending is still considerably rarer than making HTTP connections.

Spitmo’s code – like Symbian C++ in general – is object-oriented and gaining a full understanding of the trojan requires the ability to reverse engineer the content and relationships of its classes. As shown, by leveraging the class information in the binary it is possible to reconstruct the content of the malicious classes to a high degree using static analysis with IDA Pro.