Virus Bulletin

Copyright © 2020 Virus Bulletin

Together with email1 the web is one of the two major malware infection vectors through which organizations and individuals get infected with malware. Most organizations use security products to minimize the risk of malware making it onto the network this way, thus avoiding having to rely on security products running on the endpoint.

In the VBWeb tests, which form part of Virus Bulletin's test suite, we measure the performance of web security products against a range of live web threats. We publish quarterly reports on the performance of the products that have opted to be included in our public testing. The reports also include an overview of the current state of the web‑based threat landscape.

Winter 2019/20 continues to be more interesting than previous years when it comes to exploit kits, and we are still seeing new kits emerging. At least 11 kits2 are currently active and in this test we caught eight of them: RIG, Fallout, Spelevo, Underminer, KaiXin, Purplefox, Capesand and Lewd.

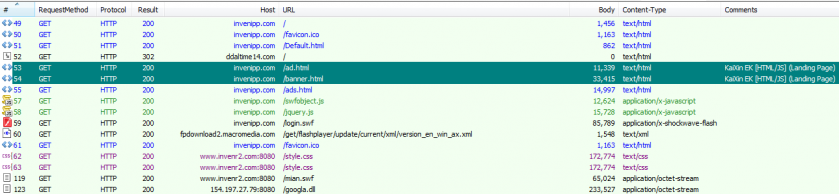

KaiXin exploit kit traffic.

KaiXin exploit kit traffic.

The most recent kits to emerge were Capesand3, found by researchers from Trend Micro delivering njRat, and Bottle4, found by @nao_sec delivering a stealer that targets users in Japan.

Other malware downloaded by the various exploit kits included: Danabot, Smokeloader, Trickbot, Raccoon, Dridex, Hidenbee and Qakbot.

We also saw more than 800 instances of malware downloads from around 90 families including Emotet, Trickbot, Ursnif, Mirai and Ransomshade. Fortunately, the tested products had very few problems blocking malware in any of these categories.

And as was the case in the Autumn 2019 test, products also had few problems blocking phishing pages.

It should be noted that one of the products included in this VBWeb test is a cloud-based product. As with the other products hosted in our lab, we replay previously recorded requests through cloud-based products5, but as we do not control the connection between the product and the Internet, we cannot replay the response.

Thus it is possible that a request that results in a malicious response in our test lab results in a non-malicious response when replayed through a cloud-based product. We consider such cases full blocks, as this is the user experience, but because a cloud-based product isn't always served the malicious content by the exploit kits, for the purpose of calculating block rates we only count these instances with a weight of 0.5. However, in the case of the particular cloud-based product included this test, all exploit kits were blocked, meaning that the weighting would not have made a difference.

| Drive-by download rate | 100.0% |  |

| Malware block rate | 99.9% | |

| Phishing block rate | 96.1% | |

| Cryptocurrency miner block rate | 100.0% | |

| False positive rate | 0.0% |

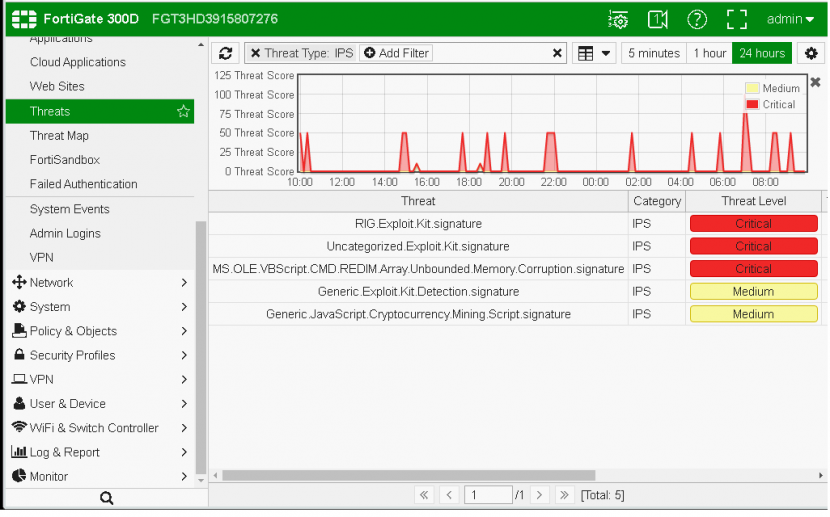

Fortinet's FortiGate appliance extends its unbroken run of VBWeb awards after having blocked all drive-by download cases (exploit kits) and having missed only one of more than 800 direct malware downloads. With over 96 per cent of phishing sites blocked, this kind of malicious site isn't a significant problem for FortiGate either.

Fortinet FortiGate..

| Drive-by download rate | 100.0% |  |

| Malware block rate | 99.1% | |

| Phishing block rate | 96.8% | |

| Cryptocurrency miner block rate | 100.0% | |

| False positive rate | 3.0% |

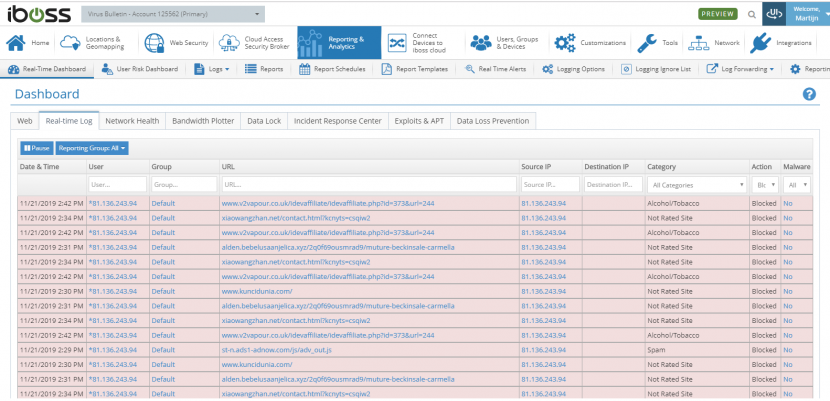

iBoss once again blocked all drive-by download cases (exploit kits) in this test, as well as all but a few directly downloaded malware samples. iBoss also blocked almost 97 per cent of phishing sites. A fourth VBWeb certification is thus fully deserved.

iBoss.

iBoss.

|

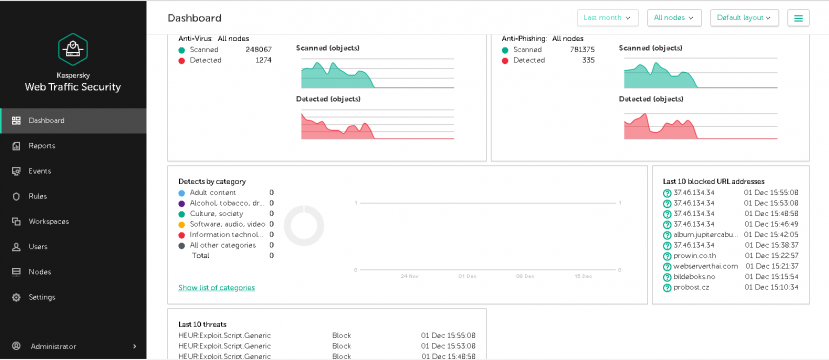

Kaspersky's web security product was also tested. Unfortunately, a routing issue caused by Virus Bulletin resulted in the product being unable to download updates – something that wasn't discovered until the end of the test. Indeed, even in this setting Kaspersky performed so well it easily achieved another VBWeb certification, but we do not think it fair to include the numbers. We look forward to seeing Kaspersky's real performance in the next test. |

|

Kaspersky Web Traffic Security.

The test ran from 15 November to 1 December 2019, during which period we gathered a large number of URLs (most of which were found through public sources) which we had reason to believe could serve a malicious response. We opened the URLs in one of our test browsers, selected at random.

When our systems deemed the response sufficiently likely to fit one of various definitions of 'malicious', we made the same request in the same browser a number of times, each with one of the participating products in front of it. The traffic to the filters was replayed from our cache within seconds of the original request having been made, thus making it a fully real-time test.

We did not need to know at this point whether the response was actually malicious, thus our test didn't depend on malicious sites that were already known to the security community. During a review of the test corpus some days later, we analysed the responses and discarded cases for which the traffic was not deemed malicious.

In this test, we checked products against 700 drive-by downloads (exploit kits), 864 direct malware downloads and 441 phishing sites, a category which also includes sites that trick the user into calling a phone number. To qualify for a VBWeb award, the weighted average catch rate of these two categories, with weights of 90% and 10% respectively, needed to be at least 80%.

The test focused on both HTTP and HTTPS traffic. It did not look at extremely targeted attacks or possible vulnerabilities in the products themselves.

Data for the test was provided by various public sources as well as an API provided by Active Defense6.

Each request was made from a randomly selected virtual machine using one of the available browsers. The machines ran either Windows XP Service Pack 3 Home Edition 2002 or Windows 7 Service Pack 1 Ultimate 2009 and all ran slightly out-of-date browsers and browser plug-ins.

1 See the regular VBSpam reports on the email-based threat landscape and email security products’ ability to protect email accounts: https://www.virusbulletin.com/testing/vbspam/.

2 https://blog.malwarebytes.com/exploits-and-vulnerabilities/2019/11/exploit-kits-fall-2019-review/.

3 https://blog.trendmicro.com/trendlabs-security-intelligence/new-exploit-kit-capesand-reuses-old-and-new-public-exploits-and-tools-blockchain-ruse/.

4 https://nao-sec.org/2019/12/say-hello-to-bottle-exploit-kit.html.